Novel Writing Workshop

Spring 20246 Wednesdays

6:30 p.m. to 8:45p.m.

2-28-24 through 4-10-24

No Class 3-13-24

Synchronous online by Zoomupdated 4-10-24

Good Luck with your novels!

Just Sit Down and Keep Doing It!This Page will remain available till

approximately June 15, 2024Some things to do (post-class assignments)

Here are a couple of resources for writing short stories. One from writers.com offers several possible structures, including Freitag’s pyramid: https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-story-outline

A couple of books that are old but useful are Master Class in Fiction Writing by Adam Sexton and How Fiction Works by James Wood. I often get older books at bookfinder.com.

The best sources for where to submit are the classifed section at aNewPages.com. There are others online. I have a somewhat out-dated list on my website: https://www.meredithsuewillis.com/places%20that%20publish.html

April 2024 Adventures in Editing with Danny Williams

Article by Alison Louise Hubbard about how she published her first novel:

My Historical Fiction, True Crime novel, THE KELSEY OUTRAGE, The “Crime of the Century” was published by Black Rose Writing in January, 2024.My journey from writing to publication began in Meredith Sue Willis’s Novel class at NYU. I wasn’t sure exactly when I had taken that first class, but on picking up my copy of Meredith’s book, OUT OF THE MOUNTAINS, I read her inscription: “To Alison, with best luck on your novel! 10-24-11.”

Oh, no! I thought. Did it really take me that long? For anyone attempting to write or publish a book, fear not. It probably will not take you that long. But if it does, take comfort in one of the things I learned along the way: each book in its own time.... Continued here

New book by another former student!

Patricia Park's new novel WHAT'S EATING JACKIE OH?, comes out on 4/30. JACKIE OH. She is inviting everyone to a book signing at the Strand on Tuesday, 4-30-24 at 7:00 p.m. She sayds, "JACKIE OH is appropriate for ages 12 and up, 12 (grade 6) and up, so it'd mean the world if you can share the book with teachers, students, and kids in your life...as well as adults."

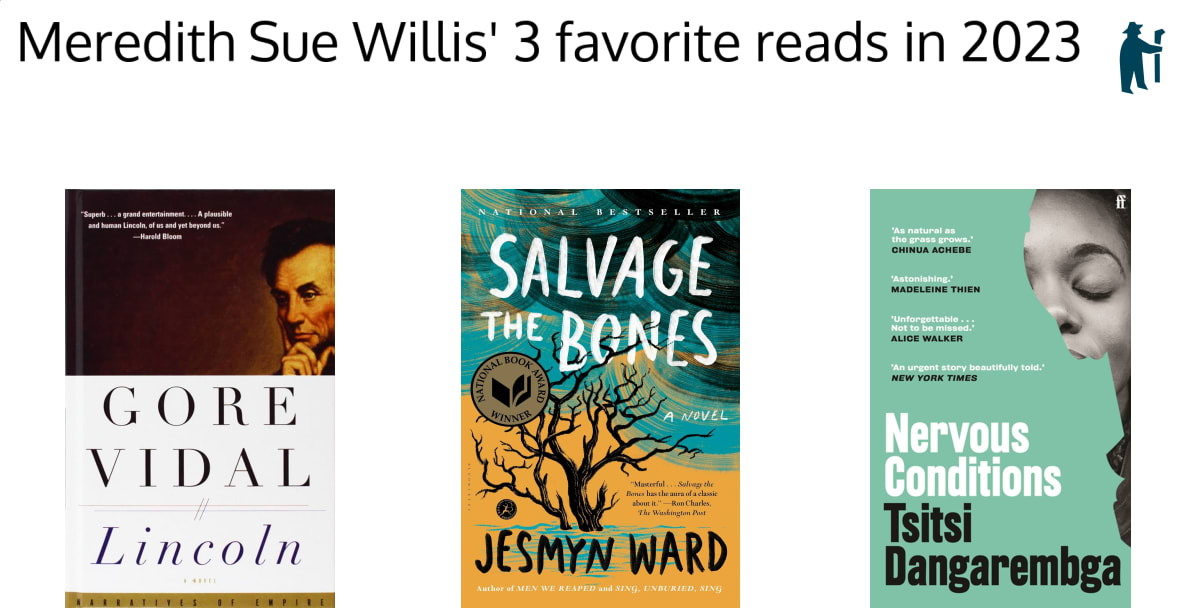

A few of my current favorites novelists

Do you know them? Living and dead, best sellers and not, all have vibrantly living work. See below for names.

Homework for 3-20-24 will be delivered to you sometime on 3-27-24;

Homework for 3-27-24 is due by midnight 3-27-24.

MeredithSueWillis.com

Current Class

Presentation/Critique Schedule

Weekly Topics

Danny Williams' March Adventures in Editing

Please note that this site changes often during the semester. It will be updated at least once a week, so check back often.

For an overview of weekly topics, click here.

Current Week's "script" is posted by Noon of class day

Optional Text for this Course: Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel by Meredith Sue Willis. This text is not required. (Available NYU Bookstore, from the publisher, and from all the usual online suspects including Bookshop.org.)

Some Optional Things to Read/Do:

New York Times piece about a writing excercise in Radical Empathy

About Character Arc by Susan DeFreitas on Jane Friedman's Electric Speed

Writing ideas from Kurt Vonnegut by Suzanne McConnell.

Why a manuscript gets rejected--emphasis on the query letter and opening pages.

A good basic piece on setting fiction in the past (genre of historical fiction but also more) by Garth Petterson.

Do you need ideas for starting your novel? Check out MSW's article online from The Writer: "How to Get a Novel Started."

Deep Point of View (from Masterclass.com)

Meredith Sue Willis's Book on Novel Writing: Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel.

Danny Williams' March Adventures in Editing

Samples of MSW's writing, see the online stories

Samples from her novels

Grandma Shiksa

Little Red

My Boy Elroy

Rescue

The Sweetest Man Who Every Lived (Then scroll down.)

Weekly Topics (Subject to change)

Week 1.

2-28-24

Business and basics like Micro/Macro writing; Process and Product; Description (why concrete description using the senses is vital for reader AND writer). Places, characters.

Week 2.

3-6-24

Dramatize and Summarize. Dialogue at the heart of fiction; scene as the building block of novels Dramatize is essential, but also essential is Summarize. The archipelago method of drafting a novel.

Presentation of Student Work for Critique

No Class 3-13-24

Week 3.

3-20-24

How to tell the story: Point of view.

Presentation of Student Work for Critique

Week 4.

3-27-24

Logistics. Pacing. Things novels do better than movies (monologue, inner speech. flashback, and other manipulations of time)--and what novels can learn from film (the silver screen visualizing technique; the Beat Sheet; continuity; logistics).

Presentation of Student Work for Critique

Week 5.

4-3-24

Common structures; Big Bins; When to Outline. Arc of story; story vs plot vs structure.

Presentation of Student Work for Critique

Week 6.

3-10-24

Monologue (inner speech); “Continuity" and Macro Revision (revising whole novel manuscripts). Close revision.

Presentation of Student Work for Critique

Session 1

2-28-24

Aspects of Description

Business and basics like Micro/Macro writing; Process and Product; Description (why concrete description using the senses is vital for reader AND writer). Places, characters.

Assignments due for Session 1:

Reading Assignments Due 2-28-24:

Read this short excerpt from Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel: Click here, then click on the "Read an Excerpt." Optional: If you have the book, read or review "Strategy 1: Separate Process and Product."

A piece from The Guardian on adverbs

Also read this page about Getting the right spacing between paragraphs in Word

FYI: Look over copy editor's marks for times when you want to do hand written mark-ups--or understand the ones MSW puts on your pages!.

Writing Assignment Due: Send MSW the first page of your novel. Everything you write for this class should be part of your novel. If you already have a draft, just copy and send the first page. If you don't have a first page yet, make one up: you can always change it later. MSW will make a single file and send the first pages to the whole class to act as an introduction of you and your work to the others. Note: this is due on class day, not before.

I. Business

A lot of business today--disclaimers--apologies to those who have taken this course before!

This class welcomes beginning novelists as well as writers who are well-underway on a novel and need further discussion and stimulation to continue or restart. We will cover a lot of basics fast, beginning with a survey of common terms for discussing novels and a look at novel structure in general. If you feel you need more of the basic terminology and ideas, please take a look at the teacher's book, Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel.

This syllabus is subject to change and will be updated regularly online, so please check this web page at least once a week. Access to the website is also available from MSW's home page. Look at the top left.

All writing, homework, and presentation selections should be from the novel you're working on.

During the course, you may bring a total of up-to 40 manuscript pages for critique (some of these pages will be for the whole group, some only for the teacher). Assignments are optional and go only to MSW. Anything you turn in to MSW, however, counts towards the total of 50 pages to be reviewed during the semester.

Please be prepared to discuss the work of classmates when they present.

Presentation pieces go to the instructor and whole class. Homework assignments go only to the instructor.

Take a look at weekly topics.

Sign up for class critiques

Pick a session to present 5-10 pages to the class. Everyone should read the material BEFORE class (it will not be read aloud), and the presenter needs to e-mail .doc files to everyone by Sunday night of the session when you will present.

I'm be sharing list unless I hear otherwise.

Please send MSW by chat or e-mail your snail mail address

Names you want to be called; preferred pronouns; corrections to e-mail, etc.--please use the chat or e-mail me.

Readings for homework are mostly online, and some are optional.

All writing should be from the novel you're working on.

II. Things that happen in the class sessions:

Macro discussions and exercises (big picture stuff); Micro discussions and exercises (detail, especially concrete detail using the senses).

Mini-lectures (MSW talks--usually short--5-7 minutes).

Discussion (as much as possible)

In-class writing

Sharing in-class writing; sometimes teacher shares homeworks

Formal presentations of your work for critique

III. Three Kinds of Responses to your writing

1. The weekly assignments should be @ 2-3 pages long. They are not required, but are a good way to move your novel forward. These pages are sent only to MSW. They are due on the day of class. If they don't arrive that day, there is no guarantee they will be returned by the next session. You may send longer passages (total for the 6 weeks is still 40 pp).

2. Substitutions: especially for people taking this class again, or who have an in-process novel--you may send any pages you want to the instructor for feedback. These pages are sent only to MSW.

3. Presentation pieces for critiquing (as short as you'd like, but no more than 10 pp. double spaced, 1 inch margins, roughly comparable to 12 pt. New Times Roman Type face) are sent to the entire class. These presentation pieces are to to arrive in people's e-mail in boxes by Sunday night before the presentation.

4. Occasional brief oral responses to shared in-class writing.

5. MSW chooses a few samples of homework writing to read and make certain points.

VIP/Repeat: the total number pages you may turn in to MSW cannot exceed 40. This includes worked to be critiqued by the whole class and assignments sent only to MSW

IV. Zoom guidelines

-- Please have your camera turned on.

-- Put yourself on mute when you're not talking so we don't have to hear your puppy, your partner rustling in the refrigerator, etc. The mute button is at lower left of the Zoom screen.

-- Raise your physical hand if you want to speak.

-- Speak one at a time--in practice, this usually means waiting for the instructor to call on you.

-- Try to be succinct.

-- Listen and respect each other's ideas. We are writing different kinds of novels. Try to make suggestions based on helping each other write the best novel of the type we are writing.

-- Use the chat function for procedural notes to the instructor (you got a text from a classmate who can't get in; the name of a book you couldn't think of and wanted to share, etc.)

-- Apologies in advance: I may have to interrupt/cut you off. We try for equal time for each person, and I also have an ambitious plan for what to cover.

-- Technical note for Mac Users on Zoom: I am told that the Share Screen sometimes looks small. Try using the drop down menu at the top and setting it to "100%"

V. Go round of introductions-- name (do we call you what it says on your Zoom image?); one sentence about what you like to read or other information that gives a sense of your background/interests. We'll describe what we're writing at another time.

VI. WRITE

Using Timed Writing describe an important room or other space as your main character enters it for the first time. Focus on the senses--especially those other than sight).

Consider psychological accuracy: what does the character notice first? Temperature? Sounds? An odor? Try to organize it as the characteer would as he/she/they come into it for the first time--that is, not every possible detail, but maybe sound first or temperature or an overview.

In Timed writing, you write steadily for given period of time. Write slowly but steadily. If you get stuck, repeat a word or write what you see around you until you get back on track. Try to keep the words flowing.

Share.

VII. Process and Product

Separating them is one of the most important disciplines you can master.

VIII. Description & the Senses in novel writing

We just focused on the senses, but I want to make a couple of general points about description.

Extremely-Mini-Lecture on Description and Its Many Uses

First: Concrete description is almost always best in fiction and memoir. Like the Courbet apples above, we best communicate what we see in our minds by sharing the lowest common denominator: red, warm, smooth, crisp, juicy. That is to say, sense details. It's not the only thing in writing, but it is essential. Novels generally don't have illustrations, and we don't have actors to give the timbre of the voice or costume designers to give fabric and folds of the cloak.

Second: Description is for the writer's process of writing as well as for communicating with the reader. Lots of rich description will help you see your work more completely and clearly and may even give you ideas for new scenes, new characters, new depth! I generally over-write as I make my first draft, then cut.

Third: In your final product, which is for others, cut most of the description you drafted. Make your descriptions as concise as possible, retaining only the very best details, See "The Lady Sheriff."

All senses (not just sight) come into play.

Here's an example from a short story-- "Consultation" by Ariel Dorfman. What senses are missing?

Here's one I like that describes a person.

IX. BREAK

X. Write a Macro Exercise

Short Macro exercise about the novel you are planning/engaged in.

4 minute description of your novel. (Not a pitch or praise, just factual)

- Genre if you know (See Types of Novels )

- Length (take a guess)

- Like format for reading it (hard copy? Borrowed from library? On a tablet? E-book?)

- How is it told? Point of view?

- Chronological order or start at the end?

Again, this is an exercise to start envisioning your novel as a whole. Assume all of this will changes.

XI. Discuss.

XII. Common vocabulary:

See Terms we'll be using this semester.

Process versus product

pacing

When to dramatize, when to summarize.

When to use a full scene, when to stop time, elide. Check out

https://www.meredithsuewillis.com/Ellipsis%20etc.pdf

Scene and summary. What is Scene? Why is it important?

Essential importance of Point of View in all fiction

XIII. How do we talk about novels?

Who has been critiqued (in class, by peers, by teachers, by editors?)

What do you find most useful? Not useful? For me, it's when people all agree something is wrong, plus bits of practical knowledge than readers/responders all have.

How to make this novel (scene, passage) the best it can be at what it wants to be.

Your Responsibilities as the writer getting critiqued:

When you give class members copies of the pages you want critiqued, include questions!

Make sure people get the piece in time to read and respond!

Listen first, then later respond, ask more questions.

Your responsibilities as a critiquer:

Perhaps most important: be a reader and talk about your reactions.

For this class: at least a short paragraph of holistic response and/or answers to the writer's questions.

Even better: notes in the text (what I do: try to catch typos; look for things that can be cut--tighten; things that could be clarified; point out phrases and parts I like)

Objective is to help a writer write the best novel possible of the type they are writing.

XIV. SCHEDULE PRESENTATIONS FOR CRITIQUE.

This is for many people the most important part of a workshop like this.

PLEASE GET WORK TO WHOLE CLASS BY SUNDAY NIGHT.

Consider using the critiquing sheet mentioned above (or your own variation on it) for responses.

Go to the list below and send me a preferred date ASAP-- everyone gets to go once, two people a night.

XV. WRITE

Again focusing on the senses, describe a character (a minor character may be best) that your main character meets for the first time. Remember people can have smells too, and hair texture, and their voices carry a lot in the timbre and accent.

XVI.

Homework and readings for Session Two 3-6-24

Writing Assignment Due 3-6-24:

Polish up one of the sense descriptions from today: The first time the protagonist meets a person or enters a space or the first time the protagonist meets a minor character. Focus on senses other than sight.

Also consider who is telling this? A first person narrator? The main character from 20 years in the future?

Reading Assignments Due 3-6-24:

(Optional) Two chapters in Ten Strategies: "Strategy 1: Separate Process and Product" and "Strategy 2: Taste It, Touch It Smell It..."

Read "The Lady Sheriff" as an example of over-writing in process and thinning the product. Here are some samples from Joyce's "The Dead" with a lot of concrete observation and sense details.

Make sure you've at least skimmed the first pages of the other class members to learn something about the books they are working on.

Read, critique, be ready to discuss the presenters' work for 3-6-24.

A story called "Consultation" by Ariel Dorfman.

Here are several descriptions I like from James Joyce's The Dead: Everything is built with concrete observation and sense details

Check out reedsy's dialogue punctuaion rules: https://blog.reedsy.com/guide/

how-to-write-dialogue/ dialogue-rules-punctuation/

Session 2

3-6-24

Scene and Dialogue

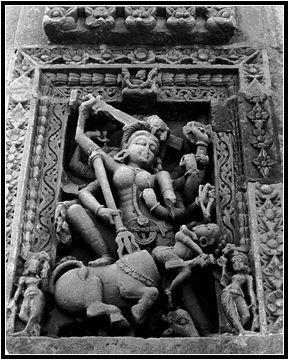

Durga fights a demon; Jane startles Mr. Rochester; Bela Lugosi

as Dracula;

From Here to Eternity horizontal kiss scene!; Polynesian

exploration by archepelago

Scene (made of dialogue and more): the Building Block of Novels. It is essential to dramatize, but we also frequently need to summarize. The archipelago method of drafting a novel.

Presentation of Student Work for Critique

Presentation/Critique Schedule

Homework and readings for 3-6-24

Writing Assignment Due 3-6-24:

Polish up one of the sense descriptions from today: The first time the protagonist meets a person or enters a space or the first time the protagonist meets a minor character. Focus on senses other than sight.

Also consider who is telling this? A first person narrator? The main character from 20 years in the future?

Reading Assignments Due 3-6-24:

(Optional) Two chapters in Ten Strategies: "Strategy 1: Separate Process and Product" and "Strategy 2: Taste It, Touch It Smell It..."

(Optional) Class member Danny Williams' March Adventures in Editing

Make sure you've at least skimmed the first pages of the other class members to learn something about the books they are working on.

Read, critique, be ready to discuss the presenters' work for 3-6-24. See the suggested questions to address here.

If you haven't already, read "The Lady Sheriff" as an example of over-writing in drafting then thinning (process and product). Also, for reading, here are some samples from Joyce's "The Dead" with a lot of concrete observation and sense details.

Read, if you haven't already, this exceprt with no sense of sight from a story called "Consultation" by Ariel Dorfman.

10 Tips for Strong Scenes from Masterclass.com. These are particularly aimed at commercial novels, but worth looking at for anyone.

Check out Reedsy's dialogue punctuaion rules: https://blog.reedsy.com/guide/

how-to-write-dialogue/ dialogue-rules-punctuation/

- Article by Emily Harstone that distinguishes three forms of publishing: tradtional, self, and vanity. It also has some good links.

I. Business

Is everyone signed up for a presentation? How did you decide to respond? Holistic note? going into Word's "review" function with comments etc.? Printing out, writing on the paper, then scanning to return?

II. Go over first pages...

.... for point of view, voice, and tenses. These are major issue in novel writing because they are about how you tell your story. Once you find the best way to tell it, things will move much more smoothly.

III. Common vocabulary:

See Terms we'll be using this semester.

Process versus product

pacing

When to dramatize, when to summarize.

When to use a full scene, when to stop time, elide. Check out

https://www.meredithsuewillis.com/Ellipsis%20etc.pdf

Scene and summary. What is Scene? Why is it important?

Essential importance of Point of View in all fiction

IV. Presenter One: Norman Danzig

V. Write

A quotidian scene: could be in almost any novel.

Put a wedding for your novel. This could be a major dramatized moment in your novel, or it could be something observed by the main character or remembered or thought about. It might be merely a shop window with a wedding dress, a note in a newspaper about a British Royal getting married--or a marriage notice for the protagonist's ex.

Perhaps your character is ambivalent about marriage as an institution. Whatever.

Just have it a part of your novel.

VI. Share

VII Mini-lecture on scene

Dialogue is the dramatic heart of a scene, and scene is the building block, the essential structure, of a novel.

Here's a little about scene. Let's look at one: "Three Ten to Yuma" by Elmore Leonard. Leonard was famous for his focus on dialogue. (If you've never read it, don't miss his famous 10 Rules of Writing).

In common speech, "scene" is the place where an action or event occurs, such as the scene of the crime. It is also commonly used to refer to a public display of passion or temper as in, "She tried not to make a scene." It is also a sphere of activity, as when we speak of observing the political scene. In slang, it is a situation or set of circumstances– "a bad scene.

In theater, film, and novel, it is an essential unit of action. In drama, there is a new scene when a new character enters. The setting is fixed and the time continuous, usually "real" or natural time. In film, a scene is a shot or series of shots constituting a unit of continuous related action. In the novel, it is above all a dramatized moment– shown, not told. It can include dialogue, monologue (thinking) description, action, etc. etc. The dynamics change. People talk and act. Something happens.

We remember great scenes in movies and novels.

In fiction, while there are lots of things besides scenes– passages of narration and long internal monologues, for example– most writers eventually come to the point where they want to dramatize their story with a scene. Dialogue or other interaction between two or more characters often marks the heart of a scene. You can have pages and pages of narration, or pages and pages of the vicissitudes of one character's thoughts or suffering, but the building block of fiction is a series of scenes with connecting and surrounding material.The scene is the way the story moves to its next level: this is where the other parts of the story come together; or, it may be the beginning of everything, after which the next parts deal with the repercussions of this dramatized part.

A scene is "dramatized," although not necessarily dramatic in the sense of having a lot of shouting or overt action. It generally demonstrates or "shows" rather than tells.

One excellent way to outline a novel is to list twenty or thirty scenes--and then write them. More about this later with the Archipelago method of drafting a novel.

One of the optional readings I suggested for today was 10 Tips for Strong Scenes (from Masterclass.com. This is worth looking at but it, like so many articles for writers, is really about revision--the product--rather than the preocess of drafting. So look at it as some good ideas for critiquing or revising your work.

VIII. Break

IX. Presenter Two: Alexis Gogh

X. Archipelago or Scenic method of drafting a novel

Chapters are largely arbitrary, arranged for ease of reading, more or less short story length (or what a 19th century serial would have offered each issue). I believe that the true building block, the structuring element, of a novel, is the scene, just as it is in those other dramatic genres, film and theater.One of my favorite ways of thinking about a novel came to me after I read a book about the early exploration of the South Pacific by the ancient Polynesian people. They used double-hulled vessels like the one in the picture, and proceeded by traveling East, not all the way across the vast Pacific, but in small stages, from one island to another, often settling and living for generations on one island or archipelago before setting off again.

An archipelago is, of course, a group of islands, which are in fact the tips of an underwater mountain range. I began to see my just-begun novel as that under-water mountain range. My idea, my vague sense of the story and material was still largely hidden from me.

What stood out for me, though, were certain mountain tops: islands of drama--scenes. These were vivid and clear to me. Each island in the archipelago of my novel is a scene. I write those first, because I can see them clearly.

Then, once all the islands of drama are drafted, I can go back to the beginning and take my double-hulled canoe of narrative and link up my scenes in the form that a reader would experience.The scenes are the essential dramatic peaks. They shape the novel and bring the reader across the story.

This also works if you've drafted your novel and it feels disorganized. If you focus on the high points, perhaps with building tension as movie scripts do, you can chart across through your material.

XI. Write: List the five or seven or nine or eleven most important scenes in your novel. If you don't know them already, make them up.

The obvious follow-up to this is to begin to draft those scenes, however roughly. If you were to do it, you would have seven or nine or eleven scenes at widely varied spots in the book, This can end up with a rough but structurally sound first draft of your novel.

XII. Assignments Due 3-20-24

Writing assignment:A fleshed out scene in your novel (dialog,setting, characters, maybe thought etc.) This could be the wedding scene or a draft of one of the archipelago scenes above.

Or, of course, substitute anything you want feedback on from your novel.

Reading assignments:

Presentation Pieces for March 20, 2024

A few samples of scene and dialogue:

A Man Told Me by Grace Paley A short short story that is single scene in the form of a monologue.

A little more on scene and dialogue:

Avoid Creative Dialogue Tag Syndrome.

So-called "inner dialogue" or monologue (from Editor's Blog).

Reedsy's six "unbreakable" rules for dialogue punctuation.

Possibly the greatest summary in twentieth century literature--told not shown!--from Virginia Woolf's To The Lighthouse, the death of Mrs. Ramsay. The bracketed "scene" is as Woolf wrote it.

(Optional) In Ten Strategies read "Strategy 6: Structuring Your Novel," pages 77-96.

Presentation Schedule

Session 3

3-20-24

How to tell the story: Point of view.

Presentation of Student Work for Critique

Vigee-LeBrun painting herself painting herself; Some "persons;" film

scene from Great Expectations

Assignments Due 3-20-24

Writing assignment:

A fleshed out scene in your novel (dialog,setting, characters, maybe thought etc.) This could be the wedding scene or a draft of one of the archipelago scenes above.

Or, of course, substitute anything you want feedback on from your novel.

Reading assignments:

Read the Presentation Pieces for March 20, 2024 (Paul O'Malley, Danny Williams)

A few samples of scene and dialogue from last session:

A Man Told Me by Grace Paley A short short story that is single scene in the form of a monologue.

A little more on scene and dialogue:

Avoid Creative Dialogue Tag Syndrome.

So-called "inner dialogue" or monologue (from Editor's Blog).

Reedsy's six "unbreakable" rules for dialogue punctuation.

Possibly the greatest summary in twentieth century literature--told not shown!--from Virginia Woolf's To The Lighthouse, the death of Mrs. Ramsay. The bracketed "scene" is as Woolf wrote it.

(Optional) In Ten Strategies read "Strategy 6: Structuring Your Novel," pages 77-96.

I. Business

Please number your pages!

Double space your homework and presentation pieces (for readability) and use conventional indentation. If you're not sure how to do this in Word, click on "Getting the right spacing between paragraphs in Word."

Please keep track of the pages you have given me. (up to 40 total, homeworks, presentation, and other).

Homeworks are due by midnight of class day. Thus homework for 3-27-24 is due midnight 3-24-24

I'll generally return homeworks during the next class day.

Please let me know how you plan to give me up to 40 pp. I'd like to know roughly when I'm getting what.

Any questions on business at this point?

II. Quick comments on various subjects:

1. Things I'm noticing in homework papers: Grounding issues: Where are we? What decade are we in? You can just say this outright or give clues. Twin towers in the background? Popular technology?

2. Use of "that" -- when to use it and when you can skip it

Essentially, use of "that" is more formal, leaving it out is informal--thus, within quotation marks, when capturing human speech, leaving it out is often natural. This is part of a larger discussion about novels and informal language in dialogue and in styles with a strong voice versus a style that is cool or formal or distant.

Examples:

I want to review the chapter that I sent you.

I want to review the chapter I sent you.

If you like grammar, look at this online discussion of "that" clauses, which are official called "noun clauses" and uses like nouns.

3. Some quick thoughts on the use of dialect and Foreign languages in dialogue:

A. Go easy on dialect. Avoid apostrophes. All English dialects pronounce "ing" without the "g," so to have a character always say "goin'" and "knowin'" makes them look stupid and makes the writer look classist. At best.

B. There are a lot of ways to show foreign languages in dialogue, few of them totally satisfactory.

Here's an example I admire from Elmore Leonard's Cat Chaser: simple and direct. The speakers are Dominicans in Florida:

De Boya sat half-turned in the front seat holding his briefcase on his lap. He would look back through the mist the Rolls raised in its wake and see Jiggs Scully’s car holding the pace, less than a hundred meters behind. They were on the freeway northbound, passing the Fort Lauderdale airport off to the right, a jumbo jet descending out of the gray mass almost directly in front of them.

Corky said to the rearview mirror, “I can put my foot into it and leave him.”

“No, we bring him along,” de Boya said. “He knows something.” They spoke in Spanish....

(Page: 305)

Samples of well-done dialect writing

Samples of ways to show foreign languages in English

III. Discussion: How is your novel going?

IV. Presenter One: Danny Williams

V. Write

Two (or more) people in your novel are sharing food together (elegant restaurant? family rushing through breakfast? an apple in a garden, whatever). Write a scene with dialogue in which one person is trying to convince the other of something.

This is, of course, about conflict, which it goes without saying is the engine moving most fiction and probably most art.

VI. Break

VII. Mini lecture on Point of View

This graphic is about third person limited or close. We know what the woman is thinking, what she is feeling (the little ghost is her inner self), and what she is seeing (the other person). It's hard to represent point-of-view, because it is so much about story-telling, not visual representation.

Once you decide how to tell you're story, you're well on your way.

But consider that a first person can have many levels of distance and closeness too--A little child's first person is different from an elder looking backon childhood, for example, You can use many tones in the same novel, but you should try to do one at a time.

Point of View Chart

Point of View examples (this loads VERY slowly)

Point of View Problems

"The Thriller Bar Scene."

My favorite:The Kilted Warrior

VIII. Presenter Two: Paul O'Malley

IX. Write again

One of your characters is in physical action, running or struggling with an object (box, coat, hedge clippers). If you are writing in third person, describe the action, if close third person of first person, include how it feels.

(or finish discussion)

X. Assignments for 3-27-24

Writing Assignment:

Complete/develop the scene of someone trying to convince someone else from in-class today.

OR--One of your characters is in physical action, running or struggling with an object (box, coat, hedge clippers). If you are writing in third person, describe the action, if close third person of first person, include how it feels.

OR--Substitute, as always.

Reading Assignments:

If we didn't get over these things, take a look (some of these load slowly):

Point of View Chart

Point of View examples

Point of View Problems

My favorite:The Kilted Warrior

Point of view problem: "The Thriller Bar Scene."

Samples of well-done dialect writing

Dialect Issues: Ed Davis's article in the Writers Digest's Blog about writing dialect.

Samples of ways to show foreign languages in English

Presentation Schedule

Session 4

3-27-24

Logistics. Pacing, Arc of the Story.

Presentation of Student Work for Critique

From Movies of the novels The Godfather by Mario Puzo; Germinal

by Émile

Zola;

Night of the Hunter by Davis Grubb; and Strangers on a

Train by Patricia Highsmith

Assignments Due 3-27-24

Writing Assignment:

Complete/develop the scene of someone trying to convince someone else from in-class today.

OR--One of your characters is in physical action, running or struggling with an object (box, coat, hedge clippers). If you are writing in third person, describe the action, if close third person of first person, include how it feels.

OR--Substitute, as always.

Reading Assignments:

If we didn't get over these things, take a look (some of these load slowly):

Point of View Chart

Point of View examples

Point of View Problems

My favorite:The Kilted Warrior

Point of view problem: "The Thriller Bar Scene."

Samples of well-done dialect writing

Dialect Issues: Ed Davis's article in the Writers Digest's Blog about writing dialect.

Samples of ways to show foreign languages in English

I. Business

Please keep track of the pages you have given me (up to 40 total including homeworks, presentation, and other).

Please let me know, if you haven't already, how you plan to give me up to 40 pp. I'd like to know roughly when I'm getting what.

Do number all pages you turn in.

Double space your homework and presentation pieces (for readability) and use conventional indentation. If you're not sure how to do this in Word, click on "Getting the right spacing between paragraphs in Word."

Any thing else you want covered in the final sessions. Next week we will do a little on structure.

Other questions or business at this point?

II. Various Odd comments:

--Copy editing marks for times when you want to do hand written mark-ups--or understand the ones MSW puts on your pages!.

--I am writing a lot of notes asking when exactly this takes place--either just date it, in a title or in the text, or give strong hints with newpaper headlines or technology (print or digital news?)

--How close to the present time can your novel be?

--Pay attention to physical action. Make it as clear as possible. If you are writing in third person, describe the action, if close third person of first person, include how it feels. A good technique is to imagine the action scene as if you were watching it as a movie.

--Watch out for "making it new"-- writing as if everything were happening for the first time so the sense details are completely fresh, like a baby looking wonderingly at the world. This is a nineteenth/twentieth century technique which can be utterly wonderful--it canalso can slow things down, sometimes to the point of being turgid. Sometimes the most creative and beautiful language is in conflict with the pacing of the story. (Need I say again, this is about revising, not drafting?)

III. Finish go-round on how my book is going: Norm, Danny, Lauren, Mark

Anyone want to add any break-throughs or discoveries or small or large obstacles?

IV. Presenter One-- Louise Williams or Linda Atlas

V. Mini-lecture on logistics, physical action, and group scenes

From a movie of Zola's Germinal; from The GodfatherLogistics is how to move people around in the physical world in your imagination and the reader's. This can be large masses of people (strike scene from a movie of Zola's Germinal) or a close up of a gesture (The Godfather) or physical action.

We talked about point of view for how to tell the story, but there is also point-of-view for how to make it clear (again, to you the writer and to your reader) about who is where. Sometimes, if the scene is full of people, it helps to imagine the teller as a fixed camera or a character standing next to a van in the northeast corner of the plaza. Write only what is seen from that vantage point. This will help keep the reader--and you the writer--oriented. Even if you have a multiple viewpoint or omniscient story, write your action and crowd scenes from a fixed point of view.

Here are some examples (more slow loading): A classic news article; The Drunken Cowpoke; a scene from one of my novels in a big dining room on a cruise ship.

Logistics also includes individual physical action: Sample from Lee Childs. Is it too much? In novel, it's at a tense moment, so it's building suspense. Also note the way he starts fairly distant from the third person limited character, but then slips deeper and deeper in: the short sentences, feelings. More and more interior.

Group scenes are notoriously tough to write--this is an area movies do well, and novels can do well, but they take some revising.

I often try to liven up the web page with stills from movies (I also often use nineteenth century illustrations): the reason is that they are, indeed, lively. They imply movement, or dramatic pauses.

Master Strategy on Logistics: Be very clear on the point of view, not just character but actual position of the story teller. Where is the teller standing? Clarify the logistics and physical action by giving a firm point of view. Imagine a fixed camera or a character standing next to a van in the northeast corner of the crowded market. Give only what is seen from that point of view. This will help keep the reader --and you the writer--oriented.

Even if you have a multiple viewpoint story, write your action and crowd scenes from a fixed point of view.

More strategies for group and crowd scenes:

- In a large crowd scene, only identify two or three individuals. Say "The twenty two members of the Ridgewood Bobcats walked into the dressing room with long faces," and then give quoted speeches only to Rob, Andrei, and Coach. The other Bobcats can mutter as a group, or hang their heads in shame, but they remain a mass, part of the scene setting.

- As above. Give proper names only to the most important characters in a group scene. (Be sure you really need the names. Proper names call attention to themselves, slow down the flow of the story.)

- Conflate. If you are writing fiction based on, say, your own large family, conflate two annoying little brothers into one. It strays from the facts, but allows the creation of one full character and eases your logistical problems.

VI. WRITE (Micro)

Put a weapon in your novel. Try to make this a passage you haven't written yet, and begin with a pretty detailed description of the object.

"Weapon" should be interpreted broadly: an old .22 hunting rifle; an angry toddler's plastic truck; a kitchen knife--or something totally unexpected. It does not have to be used (your protagonist can fantasize), or it can be used but not with deadly intent, or for protection (a branch and a growling dog).

Just put a weapon in your novel.

VII. Break.

VIII. Presenter Two-- Linda Atlas

IX. A Very Little Bit on Pacing and Arc of the Story

Move this.

Manipulation of Time in novels:

Then there is the manipulation of time, which novels do perhaps better than any other art form, using strategies like flashback, foreshadowing, and special techniques like ellipsis, summary, scene, stretch, and pause.

We talked a lot early on about scene, which is the showing rather than telling of what is going on. It is the central way we move novels forward, and I suggested that one way of drafting is to make rough versions of the 5 or 17 most important moments in the novel. It is the closest we write to real time.

To stretch or pause time, on the other hand, allows us something all human beings seek, which is to stop and examine what is happening in detail, or to hold something that is precious or beautiful or powerful frozen for a while--or to get a second change, a do-over, a Take Two or Twenty two. One reason we write (even if it's fantasy or something ostensibly very unlike our own lives) is to get a new chance--to change what happened by going back in or stopping time.

Here are some more of the specific manipulations we use:

Flashback is not just "I remembered how we used to drink lemonade on summer nights," but when we stop the forward motion (the "present time") of our story and actually describe the flavor of the lemonade, quote what was said, write a whole scene that is as full and rich as a scene in the present of the novel.

Foreshadowing is useful in certain kinds of novels, often as a means of building suspense: here's the opening of Dennis Lehane's novel Live by Night:

Some years later, on a tugboat in the Gulf of Mexico, Joe Coughlin’s feet were placed in a tub of cement. Twelve gunmen stood waiting until they got far enough out to sea to throw him overboard, while Joe listened to the engine chug and watched the water churn white at the stern. And it occurred to him that almost everything of note that had ever happened in his life—good or bad—had been set in motion the morning he first crossed paths with Emma Gould.

Is Lehane manipulating us here ? For sure, and we are pretty darn happy to be manipulated. He sets us at a particular dramatic moment in time (a life ending) and then starts to tell us how we got there.

Memory, in its various forms, including brief memories, but especially when sense impressions usefully set off (and transition to) memories. (see Proust's À la recherche du temps perdu !)

Dreams and visions. To be used sparingly, but can be very effective in in novels becuase we engage the reader's mind and imagination.

Arc of story (much more than this)

Freitag's pyramid (probably too simple for a novel)-- but it can be helpful to think about how your story moves.

X. Write

Make a Freitag's Pyramid of your book: What will the exposition be about? What is the inciting incident? The crisis? The climax? What is the unraveling or denouement?

XI. Assignments for April 3, 2024

Write:

Put a weapon in your novel. Try to make this a passage you haven't written yet, and begin with a pretty detailed description of the object."Weapon" should be interpreted broadly: an old .22 hunting rifle; an angry toddler's plastic truck; a kitchen knife--or something totally unexpected. It does not have to be used (your protagonist can fantasize), or it can be used but not with deadly intent, or for protection (a branch and a growling dog). Just put a weapon in your novel.

Read:

If you haven't read these yet:

About Character Arc by Susan DeFreitas on Jane Friedman's Electric Speed

A good basic piece on setting fiction in the past (genre of historical fiction but also more) by Garth Petterson.More:

In Ten Strategies (optional) read "Strategy 6: Structuring Your Novel."

Session 5

4-3-24

Structure, Story, Plot

Structure and novels: Freitag's Pyramid; an archipelago; architectonics (Moynihan Station);

Big Bins; an episodic epic (The Odyssey)

Assignments for April 3, 2024

Write:

Put a weapon in your novel. Try to make this a passage you haven't written yet, and begin with a pretty detailed description of the object."Weapon" should be interpreted broadly: an old .22 hunting rifle; an angry toddler's plastic truck; a kitchen knife--or something totally unexpected. It does not have to be used (your protagonist can fantasize), or it can be used but not with deadly intent, or for protection (a branch and a growling dog). Just put a weapon in your novel.

Thinking Exercise:

Try a Freitag's pyramid of your novel.

Read:

If you haven't read these yet:

About Character Arc by Susan DeFreitas on Jane Friedman's Electric Speed

A good basic piece on setting fiction in the past (genre of historical fiction but also more) by Garth Petterson.

More:

In Ten Strategies (optional) read "Strategy 6: Structuring Your Novel."

I. Business

Notes on Final Extra Pages: All pages for response from me must be in my in-box by Sunday night, April 14,2024. I am going away for a few days immediately after the class ends, so it will be at least a week before I return this work. If, however, you don't get your pages back by Wednesday, April 24, 2024, please get in touch and let me know!

Keep track of the pages you have given me (up to 40 total including homework, presentations, and other).

Number your pages and double space your homework and presentation pieces (for readability). Use conventional indentation. See "Getting the right spacing between paragraphs in Word."

Any thing else you want covered in the final session, let me know. We'll be working a little on micro and macro revision.

II.

Tonight:

Various novel structuring methods: Architectonics, Story, Plot. Big Bins; Common Structures. When to Outline.

Various:

One hundred tips to improve your novel or not by Ryan Chapman at Literary Hub.

Some Best Selling books (fiction and non fiction) that were rejected again and again:

Joyce’s Dubliners

Richard Hooker’s Mash

Thor Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki

James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice

Patrick Dennis’s Auntie Mame

Frank Herbert’s Dune

Laurence Peter’s The Peter Principle

and oh yes...

J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter

A couple of questions:

1. Characters from a different background, i.e. race, gender? Would Shakespeare have dared to write his "Hath not a Jew eyes? speech if he were worried about it? Finally, is there a better way to deal with the "otherness" curse that we humans suffer from?

I love this question. If you haven't read it, take a look at my article at A Journal of Practical Writing. This has a list of practical ways to do it, after the discussion of the problem.

Also, check out If Beale Street Could Talk, James Baldwin's 1974 novel in the voice of a young woman in love facing, along with her lover and their families, racism and financial strrains. Also, she is pregnant. Race is the same, but otherwise very different. How did Baldwin do it? Partly, it seems to me, just because he was passionate about his situation and his characters.

2. Establishing and maintaining character voice. I’m starting to wonder if my supporting characters are stronger than my protagonist?! Is this a common problem? I feel like I started off my book with a solid voice, but I feel that has faded in subsequent chapters. I find myself struggling to inject her personality into scenes with a lot of action. Any tips?

Interesting topic: a first person novel rarely really loses the first person: we are with/in the mind of the character. Sometimes she/he/they is self-examining, but sometimes giving us the experience. Especially true in action. In other words, the character is more or less insistent on her/his/their presence depending on what kind of passage we are in.

3.

This is a dinner conversation about the coq au vin the guests are served.

“Celia made coq au vin as if it’s no big deal, but she puts her experience and culinary knowledge to a classic like tonight’s fare, creating a memorable meal.”

“Celia made coq au vin as if it’s no big deal, but she puts her experience and culinary knowledge to a classic like tonight’s fare, and created a memorable meal.”

4. Someone asked where to find the Lo...ong interview with me: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x4PKU1FkK0c

III. Presenter One-- Lauren Thomas

IV. Write

A quotidian thing that could be in any novel:

Put some hair in your novel: your main character might be admiring a lover's hair; someone notices he has begun to go bald; discussion over a man's face hair; a hair in the soup. Whatever kind of hair, over write it to imagine it fully in your own mind. If you decide to use it later, you can cut out some of the detail.

V.

A very little (left over from last week) on Pacing and Arc of the Story

Manipulation of Time in novels:

Manipulation of time is something novels do perhaps better than any other art form, using strategies like flashback, foreshadowing, and special techniques like ellipsis, summary, scene, stretch, and pause.

We talked a lot early on about scene, which is the showing rather than telling of what is going on. It is the central way we move novels forward, and I suggested that one way of drafting is to make rough versions of the 5 or 17 most important moments in the novel (archipelago method of drafting). It is the closest thing in prose narrative to real time.

To stretch or pause time, on the other hand, allows us something all human beings seek, which is to stop and examine what is happening in detail, or to hold something that is precious or beautiful or powerful frozen for a while--or to get a second change, a do-over, a Take Two or Take Twenty-two.

One reason we write (even if it's fantasy or something ostensibly very unlike our own lives) is to get a new chance--to change what happened by going back in or stopping time.

Here are some more of the specific manipulations we use:

Flashback is not just "I remembered how we used to drink lemonade on summer nights," but when we stop the forward motion (the "present time") of our story and actually describe the flavor of the lemonade, quote what was said, write a whole scene that is as full and rich as a scene in the present of the novel.

Foreshadowing is useful in certain kinds of novels, often as a means of building suspense: here's the opening of Dennis Lehane's novel Live by Night:

Some years later, on a tugboat in the Gulf of Mexico, Joe Coughlin’s feet were placed in a tub of cement. Twelve gunmen stood waiting until they got far enough out to sea to throw him overboard, while Joe listened to the engine chug and watched the water churn white at the stern. And it occurred to him that almost everything of note that had ever happened in his life—good or bad—had been set in motion the morning he first crossed paths with Emma Gould.

Is Lehane manipulating us here ? For sure, and we are pretty darn happy to be manipulated. He sets us at a particular dramatic moment in time (a life ending) and then starts to tell us how we got there.

Memory, in its various forms, including brief summaries or little fragments. These work especially well when sense impressions set off (and transition to) memories. (see Proust's À la recherche du temps perdu !)

Dreams, day dreams, and visions. To be used sparingly, but can be very effective in in novels because we engage the reader's mind and imagination.

VI. Break

VII. Presenter Two-- Mark Evans

VIII. Mini lecture on Architectonics/Structure

Plot versus story plus character: Dennis Lehane on Elmore Leonard plots:

Where other novels zig, Leonard’s zag. Plot is not a series of bricks built upon bricks to erect a formidable edifice, but a loose collection of steps one or two primary characters take down a path that crosses another path that leads to a building with a room where more people are gathered. When one of those characters goes out the back door and down a fire escape, the original character follows and enters an alley which leads to another path which winds further away from that first path, which nobody remembers anyway because it’s, like, 10 paths back. In other words, Elmore Leonard’s plots feel less like plots and more like life.

Types of common novel structures are still excellent to use. There's nothing like a growing up story. Don't be afraid of them because you want to be unique. The bigger the structure, the more important it is to have it simple.

- Starts in present, tells how we came there (and goes on a little from there)

- Chronological order of events

- Episodic or picaresque--loose structure: a lot of stuff happens to the (usually naive) protagonist, who ends up fine at the end--everything from Homer to Henry Fielding.

- The genres often often structures to start you off: the HEA of the romance novel, the revelation of the perpetrator at the end of a mystery.

- Various types of fantasy (sword and sorcery) and science fiction.

- Summary of how you structure Multi-plot projects including Braided plots--three story lines, alternating, or in sections, coming together at the end. (This link loads very slowly).

- Coming of age novel (bildungsroman) (formative years or spiritual education)

- Fictional biography (or autobiography)

- Bins (Structure by big containers: several cities or certain years or several months of a particular year)

- When to Outline

- A few more thoughts on outlining and stories:

– The hypothetical method for creating a plot: make up a hypothetical or test plot. Write down a beginning, middle, and end. Write as if that made-up plot were your plot, but be ready at any moment to change it. This gives you a structure to work with (especially an end point) but gives preference to changes that your imagination might come up with.

– The chronological outline: This is probably worth doing at some point in any novel. Simply write a time line and make sure it makes sense. When is the protagonist's birth date? When do they first meet? What is the farthest forward in time the story goes? If you are in a fantasy world or don't know the exact year, do it as Year One, Month One, Day One. Day Two, etc.

– I always use "running outline," which is a daily record of progress and changes.

-- Beat Sheet

-- Best Seller: How to write one (James Scott Bell)

IX. WRITE: An exercise for finding the end of your book:

Write a short paragraph epilogue for your novel. This can be a kind of comment on what has happened--sometimes the main character just says something like "Now, all these years later, I still sometimes mourn the loss of...." It could also be a mini scene of the characters' "now:" our youthful hero in his nineties sitting in front of a fire; the teen-age characters now married with children. More often, it's just a short commentary in roughly the same style as the rest of the novel. The purpose of this exercise, though, is to help you think about the end of your novel.

X.

Assignments for April 10, 2024

Write:

Put hair in your novel OR the Epilogue

Read:

One hundred tips to improve your novel or not by Ryan Chapman at Literary Hub. This is amusing and, when it isn't being purely funny, useful

Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel , If you haven't read it yet, read Strategy 6: Structure Your Novel--Story, Plot, and Architectonics. (Optional)

Yiun Li in Lithub on what writers can learn from War and Peace.

When to Outline

Running outline

Session 6

April 10, 2024Monologue (inner speech); Micro and Macro Revision (revising whole novel manuscripts).

Right: Joseph Finnes in Shakespeare in Love

Assignments for April 10, 2024

Write: Put hair in your novel OR the Epilogue

Read:

One hundred tips to improve your novel or not by Ryan Chapman at Literary Hub. This is amusing and, when it isn't being purely funny, useful

Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel , If you haven't read it yet, read Strategy 6: Structure Your Novel--Story, Plot, and Architectonics. (Optional)

Yiun Li in Lithub on what writers can learn from War and Peace.

When to Outline

A sample "running outline"

I. Business

Notes on Final Extra Pages: All pages for response from me must be in my in-box by this Sunday night, April 14,2024. I am going away for a few days immediately after the class ends. It will be at least a week before I return homework for today and final extra pages. If you don't get your pages back by Wednesday, April 24, 2024, please get in touch and let me know! Stuff happens in cyberspace....

- This web page will remain up and available to you until June 15, 2024. So feel free to use, make copies, etc. After that, I'll take it down to make room for new projects.

II. Things you might find useful:

1. A class member asked for resources for writing short stories, especially how to structure short stories. One from writers.com offers several possible structures, including Freitag’s pyramid: https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-story-outline

A couple of books that are old but useful are Master Class in Fiction Writing by Adam Sexton and How Fiction Works by James Wood. I often get older books at bookfinder.com.

The best sources for where to submit are the classified section at NewPages.com. There are others online. I have a somewhat out-dated list on my website: https://www.meredithsuewillis.com/places%20that%20publish.html

2. Always fun and useful:

April 2024 Adventures in Editing with Danny Williams

3. Article by Alison Louise Hubbard (also at A Journal of Practical Writing) about how she published her first novel:

HOW I GOT MY BOOK PUBLISHED by Alison Louise Hubbard

My Historical Fiction, True Crime novel, THE KELSEY OUTRAGE, The “Crime of the Century” was published by Black Rose Writing in January, 2024.

My journey from writing to publication began in Meredith Sue Willis’s Novel class at NYU. I wasn’t sure exactly when I had taken that first class, but on picking up my copy of Meredith’s book, OUT OF THE MOUNTAINS, I read her inscription: “To Alison, with best luck on your novel! 10-24-11.”

Oh, no! I thought. Did it really take me that long? For anyone attempting to write or publish a book, fear not. It probably will not take you that long. But if it does, take comfort in one of the things I learned along the way: each book in its own time.... Continued here

4.New book by another former student!

Patricia Park's new novel WHAT'S EATING JACKIE OH?, comes out on 4/30. JACKIE OH. She is inviting everyone to a book signing at the Strand on Tuesday, 4-30-24 at 7:00 p.m. She says, "JACKIE OH is appropriate for ages 12 and up, 12 (grade 6) and up, so it'd mean the world if you can share the book with teachers, students, and kids in your life...as well as adults."

III. Query Letters:

Alexis asks, "Hi Meredith, is it possible in Wednesday’s class to go over how to write a query letter or what the characteristics of a query letter are and what separates a good one from a bad one?"

Main/best answers: 1. Research agents' websites (I'm assuming this is about querying agents). They are very explicit about what they want, including what should go in a query. 2. Be concise! A single paper page with lots of margins is best. 3. If you have any credentials (previous publications, history of writing in an other genre--journalism, grants, etc.) include that.

Here are some older queries of mine https://www.meredithsuewillis.com/samplequeryletters.html

And a piece on bad queries: https://writersweekly.com/angela-desk/worlds-worst-query-letters-11112020

IV. Me as I look back over this course:

I've been looking over what we've covered, often lightly, in these six weeks.

We began with scene and dialogue, and especially with scene as a method of structuring (archipelago method),

We touched frequently and in different ways on logistics and grounding and the manipulation of time (foreshadowing, flashback).

Much of this was in the context of revising, not drafting. My suggestions for drafting new material also came in different ways, often centering on "quotidian objects and scenes" to stimulate writing.

Most of my comments on micro revision came through looking at pages handed in. Tonight, we'll touch directly on revising novels.

V. Presenter One: Philip Ai or Dreama Frisk

VI. WRITE

A monologue: your character is lying in a hammock, on the beach, on a long train ride gazing out the window. Set them up in a slow moment of life. What goes through their mind? Memory? some philosophizing? Stream of consciousness observations?

Monologues are one of the best ways to explore character— both for the writer and the reader. In first person fiction or in a memoir, you can have a secondary character tell a story about herself/himself in dialogue. You might also get in a minor character's inner life via an e-mail letter or social media post. A friend of mine is writing a memoir, and she has a cache of old paper letters between her mother and father which she is using generously in order to give her parents, of whom she is often critical, an opportunity to speak for themselves. This is a good way to learn more about a character who feels a little flat.

VII. BREAK

VIII. Mini lecture on revision

I distinguish

- "chunky" revision, moving stuff around, writing more Mostly structure.

- "deep revision" when you go slowly and try to make it deeper and thicker.

- more tries at deep revision

- Polish-- but they do get all mixed up. Lots of

First version to second version: I just tightened. It's what I think of as soft, squishy sentences getting tougher and more wiry. By the third, I was also making changes about what information is conveyed: information about the school, and the vice-principal. The original version has two women teachers talking naturalistically, but doesn't go very far with the story. I was still in my mind just listening to how they talked, to the relationship between the narrator and Fredda. It was about what can be observed on the surface. By the third version, I had what I wanted about the narrator and Fredda in other places. The final version, with the narrator and the vice-principal, is exploring a new character, the veep. It has more about the culture of the school.

I get tremendous pleasure in seeing the story come into view like this, like an old fashioned developer bath for photos. Another way I think of this is as sculpture: I get that elephant's general bulk hacked out, then the details that come into view.

Some Specifics of novel revision:

Housekeeping: Check consistency in a character's appearance AND behavior. What have I revealed? Best technique: do a search for "Karen" and check all her details through the whole manuscript You can do this with action, too, or the appearances of certain places (do a add a new detail with each appearance).

Revision of Tenses for character: This is a bit of micro editing based on the character of the narrator. I originally wrote:

I had aleady decided I wasn't sticking around Hawkinsville for long.

This careful use of correct tense slows things down; more importantly, it takes offstage an important decision the character is making. Also, the narrator is a kid. During revision, I changed it to

I decided I wasn't sticking around Hawkinsville for long.

This is very small, but it adds directness and puts the thought in the present time of the novel. The directness is appropriate to this character. It moves the narrative toward dramatizing rather than narrating, and even moves the passage along a continuum from narrative toward scene. It isn't a scene, but moves in that direction.

MACRO-REVISION for Novels

A. Overview on Special Techniques for Revision Novels:

REMINDER: Before you do anything else, get a lot written. That is, if you work best by revising as you go, do it, but don't over-do it. Do less than you may want to. Going over what is written is reassuring. We know how to make it better. Voyaging out with new material if scary, but you need a lot of material for a novel. Get something roughly novel-sized written before you make final decisions.

This is what Matt Bell calls "Generative Revision"

- 'generative revision' -- moving from drafting chaos to new ideas, rough order, new typing!

- 'narrative revision' -- moving to structure--finding the story arc?

- 'polishing revision.' lots of editing and polishing approaches: reading backwards, reading aloud, etc.

Here is a simplification of my process:

-- Draft the whole thing if possible, but at least a hundred or a hundred-fifty pages

-- Let it rest.

-- Go through adding and enriching.

-- Go through moving things around to find the best order--look at conflict, crises, story arc, climax etc..

-- Go through again cutting and tightening. Respect your audience's time!

-- Go through for housekeeping.

-- Cut and tighten again.

-- Clean up grammar, continuity, etc.

-- Let it sit, maybe a long time.

-- Go over it again.

B. MSW's Seven Layers of Revision

I wrote up ideas from my process in an article for The Writer magazine, "Seven Layers to Revise a Novel," where I say more about some of these different types of revision.

I want to point out a couple of crucial "layers:"

1. Do a revision from the middle or three-quarter point. This will focus you on the final sections which often don't get the close attention the beginning does because of our tendency to obsess about the beginning.

2. The character/place/other proper name check: Do a search for every appearance of an individual character or bar or beach or whatever. Read just those parts to see what is missing, if you have been too repetitive, if you can spread out some of the descriptive details. Do you, in fact, need that character to have a proper name at all?

3. "Continuity" flows from #2. Check for the hero's eye color. Does it stay chocolate brown and turn steely gray fifty pages in? This is part of housekeeping, and since you are the whole crew for your novel, you're responsible.

4. Go through at a reader's pace. This is also known as a revision where you sit on your hands. Read at least a chapter without taking notes. Be aware of where your interest flagged, or where the story runs smoothly. Take notes at the end of a chapter or section, but then go on and read again, as a reader. This is almost as if you were reviewing your own novel. You're looking for pacing problems, missing information, scenes you told instead of showing.

C. Quick Revision Types from Matt Bell

Ideas on different drafts from the an article that appeared in Poets & Writers of May-June 2022): "Eight Final Revisions to Try Before You Submit" by Matt Bell. I recommend this publication anyhow, at least to look at occasionally: craft articles, classifieds, contests, conferences, etc. A lot of what he has to say is probably more appropriate for short stories, but I especially like these two ideas:

1) Go through only the dialogues--all of them

2) and cut the weakest sentence from every paragraph (I'd suggest picking one chapter or section to try this on).

D. More Novel Revision ideas

IX. Presenter Two: Philip Ai or Dreama Frisk

X. WRITE

Describe the cover of the first edition hard copy of your book.

XI. Final discussion

Go round on where you'd like to be with this novel at the end of Summer 2024.

XII. Some "Homework" for after class:

Write:

Some quotidian scenes and things to try to put into your novel as expanders and starters.

Read:

- Here are a couple of interesting articles on revision: A close reading of a well-made first paragraph (Emily Temple on True Grit) and How some contemporary writers revise (from Lit Hub).

- Seven layers to Revise your novel

Eight Final Revision Steps Before You Submit by Matt Bell

One page list of novel revision suggestions.

- (Optional) Strategy 10 in Ten Strategies "Revise Your World."

List of Presentation Dates

If you are presenting, please get the piece to the class by midnight on the Sunday before your presentation.

Session 2. 3-6-24

1. Norman Danzig

2. Alexis Gogh

No Class 3-13-24

Session 3. 3-20-24

1. Paul O'Malley

2. Danny Williams

Session 4. 3-27-24

1. Louise Williams

2. Linda Atlas

Session 5. 4-3-24

1. Lauren Thomas

2. Mark Evans

Session 6. 4-10-14

1. Philip Ai

2. Dreama Frisk

Octavia Buter, Sarah Waters, Valerie Perrin. Elmore Leonard, Richard Wright; Michael Connelly, "Mrs." Elizabeth Gaskell, Barbara Kingsolver, Denise Giardina, Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, Michelle Zauner, Jesmyn Ward, Douglas Stuart. Images are stock photos or borrowed.

Subscribe to Meredith Sue Willis's Free Newsletter

for Readers and Writers:

Please fill in your e-mail address

to receive Books For Readers NewsletterE-mail address: Subscribe Unsubscribe Complete List of Meredith Sue Willis's Books

MSW's Bookstore: A percentage always goes to

local brick-and-mortar bookstores.Images, photos, and text found on the pages of this web site may be used by anyone, but please attribute the source when it is specified. See the license below.

Meredith Sue Willis Author and Teacher is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

RESOURCES For WRITERS

NEWSLETTER ON BOOKS & WRITING

HOME

MSW's Online Classes

About MSW

MSW News

Upcoming Appearances and Publications

MSW's Books

Biography

Services MSW Provides

Contact

Journal of Practical Writing

What's On This Site

Writing Exercises