A Journal of Practical Writing II

Contents

(Unattributed Articles by Meredith Sue Willis)

Latest Articles

May 2024 Adventures in Editing with Danny Williams

April 2024 Adventures in Editing with Danny Williams

Free Indirect Discourse: Two (or Three) Points of View at Once? by Eddy Pendarvis

One Story, Forty Submissions, Ten Years by Ed Davis

The Ninety-Nine Day Novel Course by Alison Hubbard

Cultural Appropriation in Creative Writing: Considerations and Practical Approaches

A Response from Kate Gardner

Adventures in Editing with Danny Williams

And More Notes on Editing

May 2024 Adventures in Editing with Danny Williams

April 2024 Adventures in Editing with Danny Williams

March 2024 Adventures in Editing with Danny Williams

February 2024: Adventures in Editing with Danny Williams

Book Reviews for Writers: Danny Williams on Meredith Sue Willis's Love Palace

Real Life Adventures in Editing by Danny Williams

Names in Fiction by Danny Williams

Should Your Book Have a Price on the Cover? by Danny Williams

More Hints from a Professional Editor by Danny Williams

Also, check out this Danny Williams extra on publishing with university presses.

More

Best Writing Advice I Ever Heard/Best Novels for Learning to Write a Novel

The "Stakes" Method of Outlining by Suzan Colón

MSW on Character Development Through Changing Names

Thoughts and Exercises for Writing Physical Action

Literary Recycling by Ed Davis

Five Lessons from George Eliot

Structuring with the Raised Relief Map Technique

Rolling Revision: The Interplay of Big Picture and Close-Up

Some Thoughts on Self-Publishing by Allen Cobb

(See Allen Cobb's website here)Making Your Own Deadlines by Anna Egan Smucker

A Revision Technique for Novels

Literature, Genre, and Me

A short inspirational passage about the meaning of art.

On Using the Omniscient Point of View Successfully

Anthony Trollope's Discipline

A Conversation About Keeping Drafts with Suzanne McConnell, NancyKay Shapiro, Diane Simmons, and Meredith Sue Willis

Those Handy Little Binoculars by Sarah B. Robinson

On Writers Groups by Troy E. Hill

Dialogue: The Spine of Fiction

For links to a list of various articles on the web of special interest to writers, click here.

- Free Indirect Discourse: Two (or Three) Points of View at Once?by Eddy Pendarvis

- One Story, Forty Submissions, Ten Years by Ed Davis

The Ninety-Nine Day Novel Course by Alison Hubbard

Cultural Appropriation in Creative Writing: Considerations and Practical Approaches

A Response from Kate Gardner

A Brief Note on Character Development Through Changing Names

Best Writing Advice I Ever Heard/Best Novels for Learning to Write a Novel

The "Stakes" Method of Outlining by Suzan Colón

Real Life Adventures in Editing by Danny Williams

Should Your Book Have a Price on the Cover? by Danny Williams

- More Hints from a Professional Editor by Danny Williams

- Names in Fiction by Danny Williams

- Also, check out this Danny Williams extra on publishing with university presses.

Some Thoughts and Exercises for Writing Physical Action

Notes on Literary Recycling by Ed Davis

Five Lessons from George Eliot

Structuring with the Raised Relief Map Technique

Rolling Revision: The Interplay of Big Picture and Close-Up

Some Thoughts on Self-Publishing by Allen Cobb (See Allen Cobb's website here)

Making Your Own Deadlines by Anna Egan Smucker

A Revision Technique for Novels

Literature, Genre, and Me

A short inspirational passage about the meaning of art.

On Using the Omniscient Point of View Successfully

Anthony Trollope's Discipline

A Conversation About Keeping Drafts with Suzanne McConnell, NancyKay Shapiro, Diane Simmons, and Meredith Sue Willis

Those Handy Little Binoculars by Sarah B. Robinson

On Writers Groups by Troy E. Hill

Dialogue: The Spine of Fiction

For links to a list of various articles on the web of special interest to writers, click here.

Adventures in editing, May, 2024

The six-week Meredith Sue Willis novel writing class is over. It went a lot faster than the six-

week Jillian Michaels tone your abs class. Another difference between the two educational

ventures is that I’m likely to continue to apply what I learned from the former.

I’m now back to my original novel idea, which I set aside because the first-person

narrator kept wandering off the path. I’ve fired that guy, and brought in a third-person narrator.So far, he’s a lot easier to work with.

It’s the story of a disabled engineer, 62 years old. Four years after a car crash killed his

wife and severely bunged up his leg, he’s cynical, bitter, and reclusive. The arc involves him

opening up a little, and tentatively re-engaging with the world.I have no intention of finishing the thing, much less trying to get it published. But the

wise authors who engage me to look at their work do have these intentions, so I’m pretending.

The lessons I learn ought to make me even more equipped to help my writers.

Here’s one of those lessons: Consider rooting your story more firmly in its time and

place. A fellow student is working on a cool-sounding fantasy novel. The setup is a familiar one,

a rather ordinary character discovering there’s another reality paralleling ours, and they are

something different in that reality than in this one. It’s a starting point rich with possibilities.

Think Harry Potter, and Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. I haven’t

seen enough of my classmate’s work to know where they’re going with it, but their advice from

the class was to localize. Include a tie to Appalachia as often as it reasonably fits. That’s a strong

distinctive element, and an important selling point when a reader—or more importantly, a

publisher—needs convincing that this story is different and special. In their cover letter to the

right publisher, “readers of Appalachian fiction” will be a point in favor of taking a closer look.I have my engineer living in South Point, Ohio. You can probably imagine about where

that is. Across the Ohio River are the two cities of Ashland, Kentucky, and Huntington, West

Virginia. It’s a reasonable place to have an engineer make his home and career. The Big Sandy

River, between Kentucky and West Virginia, is lined with chemical plants and associated

industries. The shipping facilities shared by the three states comprise America’s largest river

port. Lots of work for engineers.Problem is, the Ohio River is a severe cultural divider in the minds of many. Mention

eastern Kentucky or southwestern West Virginia, and people think “Appalachia.” Mention

southern Ohio, and they think “Huh?” So I’m going to move Mr. Weatherholt across the river to

a small city a half hour away, like Grayson, Kentucky or Wayne, West Virginia. Then I’ll give

him Appalachian-type stuff. Maybe make him a native of the region, with cousins to interact

with, or put some guys from farther out in the hills in his poker group. I think I can write these

people. I grew up with them. And in my imaginary cover letter, “readers of Appalachian fiction”

will look better than “readers of southern Ohio (or disabled engineer) fiction.”Meredith Sue herself pointed out another weakness in the small sample I shared with her.

I wrote a conversation between Mr. Weatherholt and a neighbor who was using his washer and

dryer, consisting entirely of quotations. Twenty-three of them, like I was writing a radio play or

something. The guy’s got a dose of his beloved single-malt. I could let him take a sip. And the

woman could fold her clothes while they talk. Maybe the man will comment on some of her

garments. The conversation goes on for several minutes, so most likely one or both of them will

look at their phone, reject a spam call, and curse a little. And in a lesson learned from an in-class

exercise, I’ll use sounds or smells, not just visual details. Maybe the peaty aroma of the Scotch,

or the sound of the dryer. A little bit of stuff like this will add a lot to the reality of the scene.I will act on these two pieces of advice, and some others from the class, and do my best

job of amending my manuscript. That will plant the ideas firmly in my already terrific editing

brain. (“Terrific” is Meredith Sue’s word for the job I did on one of her novels.) That’s two more

tools I’ll have in my kit when I work with you on your undertaking.Totally Irrelevant Aside. You can skip this paragraph. Researching for a book a few years ago, I

learned the story of “Tokyo Rose.” Iva Toguri, a native-born American of Japanese heritage, had

the immense bad luck of being in Japan on family business when World War II started. Unable to

return home, and unable to get a food ration card because she would not renounce her

citizenship, she supported herself by broadcasting American music over a radio station listened

to by many of the American sailors and Marines in the Pacific. After the war, General

MacArthur’s investigators examined her work, and found that she had never belittled America,

called on sailors to surrender, or in any way done anything detrimental to the country or the war

effort. On the contrary, she sometimes slyly ridiculed the Japanese government and military on

air, and she risked prison by smuggling food to Americans in POW camps. But in the US, there

was a tremendously influential radio commentator who built his reputation on sensationalism and

falsehoods. (Imagine that!) This was Walter Winchell, and he targeted Toguri, labeling her a

traitor. The country got stirred up, and somebody bribed two Japanese men to testify against her.

She was convicted of treason, and served six years in the federal women’s prison at Huttonsville,

West Virginia. In 1976, the investigative TV show Sixty Minutes pieced together the story, and

even found the two witnesses, who admitted they had been bribed to testify falsely. President

Ford pardoned her, a veterans’ organization gave her a citizenship award, and she should have

enjoyed thirty years of life without the cloud over her head. Sadly, plain truth is no match for

spectacular lies, and many still think of her as a traitor. It’s just a story I believe needs telling. If

you’ve read this far, remember, I said you don’t need to.

Watch your Language

From the “Manifesto” of a group calling itself the “Patriotic Front”: After a sentence maintaining

that Black people are not Americans, “The same rule applies to others who are not of the

founding stock of our people as well as those who do not share the common unconscious that

permeates throughout our greater civilization, and the European diaspora.”

(And presumably, this is by one of the better masters of English in the outfit.)After fleeing from officers, the vehicle was later located in the 200 block of Oney Avenue.-

WVMetronews

(FOX40.COM) — Over 70 grams of methamphetamine, hundreds of counterfeit pills, goats and

chickens were seized from a stolen vehicle in Dunnigan, according to the Yolo County Sheriff’s

Office.“[name] confessed to strangling [name] after her body was found.” – WVMetronews

That’s harsh.And remember, unless it’s a quotation by a particularly unimaginative character, “taking the

world by storm” is never the right phrase. I found it twice in the NYT.GOOD STUFF FOR FREE! Send me a piece of what you’re working on, and I’ll spend a

couple hours with it and give some feedback, at no charge. For real, not like those offers where

you have to give them your credit card number up front, then they hope you forget to cancel

whatever it is and they can take your money without you noticing. I’m doing this because I love

my work and want more of it. And if you don’t end up hiring me, I’ll still have had the sneaky

little thrill of reading something the rest of the world can’t.

editorwv@hotmail.com

Adventures In Editing. April, 2024 with Danny Williams

The adventure around here lately is that I’ve had the opportunity to show a little of my novel idea to a bunch of other writers, and to get a peek at what they’re doing.

It’s Meredith Sue Willis’s novel writing class, six action-packed Zoom sessions. I don’t believe any of us actually wrote a novel in six weeks, but I’m pretty sure we all got at least a little more clarity on where we are going and how to get there.As you no doubt recall from last month’s treatise, my novel is actually my Plan B, hastily moved to the front of the queue when my original plan hit a wall. Some other students are also nursing infant projects, some are farther along in their journey, and one guy says he has a complete manuscript and is on his seventh draft.

We all shared one page at the beginning of the class, and about five pages later on. Because of the small sample size, most of our initial recommendations have been on the line and sentence level. Tighten the dialog, examine all pronouns, and the like. Then we got into a brief discussion of each piece, and the real stuff happened. In my own teaching, from kindergarten to college, answering students’ questions was always a real education for me. Putting what I knew into words distilled a clear picture from a foggy idea. And thus it was for some of us. Will there be any flashbacks or fast-forwards? Is this character really an asshole? What age are these people? Is it present-day, past, future, none of the above?

My novel (working title “My Novel”) draws on my experiences in the 1980s, when I worked for an agency which cared for developmentally disabled people, and also drank heavily and smoked a lot of weed. I worked in a three-client house in a family neighborhood, but in the excerpt I submitted for the class I imagined supervising one of the big eight-client houses outside of town.In one truly lovely paragraph, I described the scene in the great room, naming each of the eight ladies and saying what she was doing—pacing, laughing, looking out the window, playing with spit, whatever. The idea was to convey that the place was a lively circus of activity. “No,” came a chorus from the other authors. “Too much.” Somewhere on meredithsuewillis.com there’s an article on naming characters, and cautioning writers to hand out names sparingly. Okay, I wrote it. So according to me, whenever we learn someone’s name, we believe we ought to try and remember it. And here I was introducing eight names in one paragraph. Meredith Sue thought this might be from my background in non-fiction writing. I want to give complete information, because complete information is an ideal, and also because I wouldn’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings by leaving her out. So I replaced the paragraph with one describing the scene, but naming only two clients. Less lovely, more readable. I’m aiming for 60,000 words, so there’s plenty of time to introduce the others later on.

Lesson learned—again. If I ever submit any fiction for publication, I will certainly work with a professional editor.

In each Zoom session, Meredith Sue asked us to spend a few minutes writing from a prompt. One time it was to place a weapon—any kind of weapon—in our novel. I had my protagonist sitting in a particularly dull training session, imagining holding an invisible Nerf gun and zapping the presenter with an invisible dart once in a while. Lots of fun, and I wish I had thought of that fantasy back when I had jobs and went to meetings. So far, I have not found a good place to insert it. But another exercise was to write about sounds and smells (we get so caught up in sight), and that led me to a major improvement in My Novel. I imagined the protagonist on his first day at the eight-client rural house. He smelled fresh air and tilled earth, and heard a far-off tractor and an occasional “moo.” I liked what I wrote, and later I decided to place the guy in a three-person city site for a while, then transfer him to the large house. He could compare the new place with the street noise and artificial air of the old one. This led to shifting a couple chapters around, and I believe the manuscript is better for it.

The action takes place about 1983-1989, so I Googled around and came up with way too many potentially useful bits, including these:

The Madonna lace craze

Rubik’s Cube

“Where’s the Beef?”

Parachute pants

Return of the Jedi

The Police, Culture Club, Men at Work

The Mists of Avalon, Pet Sematary, The Little Drummer Girl

gnarly, grody, radical, chill, gag me with a spoon

Reagan was President, 1981-1989

Challenger disaster, January 1986

Without forcing the issue, I’ll use some of this. For one thing, many workers in the residential-care field were young women, so there will be opportunities to mention some clothing and music trends.

Euphemism of the Month, from WV Metronews, (with the mug shot of a beat-up guy): "According to court documents, during the arrest, police 'had to give compliance strikes to Mr. [name] in order to gain control.'”

Let me know about your own writing. Now that I’ve shown a little of mine, it’s only fair.

editorwv@hotmail.com

HOW I GOT MY BOOK PUBLISHED

By Alison Louise Hubbard

My Historical Fiction, True Crime novel, THE KELSEY OUTRAGE, The “Crime of the Century” was published by Black Rose Writing in January, 2024.

My journey from writing to publication began in Meredith Sue Willis’s Novel class at NYU. I wasn’t sure exactly when I had taken that first class, but on picking up my copy of Meredith’s book, OUT OF THE MOUNTAINS, I read her inscription: “To Alison, with best luck on your novel! 10-24-11.”

Oh, no! I thought. Did it really take me that long? For anyone attempting to write or publish a book, fear not. It probably will not take you that long. But if it does, take comfort in one of the things I learned along the way: each book in its own time.

For thirty years I had written lyrics for musical theatre. While I never had that Broadway opening I wanted, I did have touring musicals, productions, publications, and had received industry prizes. I made money; not enough to quit my day job, which was giving flute lessons, but enough to have an agent and consider myself a professional. But getting a musical from page to stage takes a village—writers, director, actors, set designer, sound person, stage managers, producers. Mounting even the smallest off-Broadway show costs millions. Many of my shows had industry “buzz” and seemed ready to launch, only to fizzle. Burned out and discouraged, I decided to step away from musical theatre for a while.

I had an idea for a novel based on an unsolved murder in my town. A plaque titled THE KELSEY OUTRAGE* marked the spot on a quiet street where a poet named Charles Kelsey had been tarred and feathered before being murdered “By Persons Unknown” in 1872. I began to do some casual research, and discovered an eye-popping tale of love, lies and lawlessness. But writing a novel was not in my wheelhouse. How would I even begin?

I went to the NYU website, found the School of Professional Studies, and signed up for Meredith’s Novel 1 class. Luckily, I found a teacher who was both structured and inspiring. I marveled then, and still marvel, that Meredith is able to read and comment on fifty pages of each student’s writing in one semester. Her charts and assignments taught me the rules of the road for this new journey: the difference between omniscient and third person POV; how to write a crowd scene; when to slow down or speed up the action; what makes dialogue crackle. Writing a novel was refreshingly calm after writing for musical theatre. Sitting at my computer, I was the producer and director, could have an unlimited number of characters in my cast and an unlimited number of scenes and props. I was free to do whatever I liked! I believe I completed my first draft in Meredith’s class the following semester. It was the journeyman work of a novice, but getting that first draft written was an important milestone.

Over the years I took Meredith’s novel class many times, as well as other novel and short story classes at NYUSPS and the New School. I signed up for summer courses at the University of Iowa; Yale; Kenyon Review; New York State Summer Writers and Bread Loaf. I attended the New York Pitch Conference and took Tom Jenks’s Art of the Story workshop. With each class my manuscript evolved and deepened. There were three significant turning points along the way. The first was when I decided to make it completely fictional. Freed from the shackles of historical truth, I used my imagination. The second was when the victim’s sister, Cathleen, became the protagonist. The third was when I cut down the number of POV characters from sixteen to five. Each of these revisions took time, but helped to make my book more focused and dramatic. Also shorter: I cut about fifty pages, ending up with 370 pages (92,000 words). I concentrated on one goal only: getting readers to turn the page.

In the fall of 2022 I began querying agents and small publishers. I found names on the internet, in PUBLISHER’S MARKETPLACE (a monthly subscription) and books such as WRITER’S MARKET. The online publication AUTHORS PUBLISH (Caitlin Jans) had lists of small indie presses that did not require agents. These are only a few suggestions; there are many websites and books out there that list agents and publishers. Querying is like applying to college. Each agent or publisher has specific requirements for what to send. Some want only the query, a one-page cover letter consisting of a hook (one line description of the novel) the book (how many words, what genre, comparable titles of successful books published within the last few years) and the cook (a brief bio). Others ask for sample pages or a synopsis also. It is very important to research who the agents are and what their MSWLs (manuscript wish lists) are, so in your one or two sentence introduction, your agent or publisher knows you have done your homework. Of the fifty-one queries I sent out, three agents and two publishers asked for the full manuscript to read. When Black Rose Writing offered a contract, I signed.

I can’t vouch for other publications. Black Rose is a small indie publisher in Texas. They are in some ways a mom and pop operation. The owner, Reagan Rothe and his wife Minna choose the books to publish, and they have a small team for design, marketing, sales and PR. They have quite a large catalogue, and were organized and professional about producing my book. They strongly encourage their writers to purchase packages for sales and marketing. After being hit with a blast of emails, I made the decision to hire Diana Bassett, who had done PR for my daughter Emily’s shoe company. Diana is young, practical, and full of positive energy.

A note here. Although I have a publisher for my book, I have spent a fair bit of money promoting it. On paper this is not a sound investment. But I was faced with a choice: let Black Rose put it out there and be done with it, or hire a pro to create an outreach and also a collection of press interviews I can keep in my “scrapbook.” I realized trying to promote my book myself would be like trying to fix my car. So far Diana has gotten me some nice interviews. (Here’s the latest: https://medium.com/authority-magazine/alison-louise-hubbard-on-the-5-things-you-need-to-know-to-become-a-great-author-c070ee882fd6). She organized my book launch (very successful: a great crowd, and sold over fifty books), and lined up another signing at Barnes and Noble in Manhasset, Long Island, in May. Beyond this, she has acted as an agent, interfacing with Black Rose, book stores, and the Long Island Authors Group, where we’re hoping to have THE KELSEY OUTRAGE in the Gold Coast Book Fair this June. Having a weekly meeting with Diana has helped me to strategize; her wisdom and experience have been invaluable.

I didn’t realize, but soon learned, that PR and Marketing are two different things. Diana does not handle social media. My daughter Emily organized a social media campaign for me before my book “dropped.” I was blessed to have her time and expertise. While my social media imprint is not what you would call high profile, and I have fewer followers than I would like, I have a URLs where people can find me, and a place to post information about events. Emily also manages my website, which I built with the help of the Authors Guild. If you check out my website, alisonhubbardauthor.com, know that it is in need of updating, and is pretty basic.

Before publication, I sent my book off to be reviewed in a few places, both organic (free) and paid. Most of the paid-for reviews cost a small amount, but Kirkus, the largest and most prestigious reviewing company, cost about $400. I decided to pay, because I wanted the imprimatur of a Kirkus review. So far my reviews, organic and paid, and on Amazon and Goodreads, have been good. That said, once your book is out there you have no control over what people will say and how many stars they will give it. I know a Black Rose author who had a person post a one star review because of the controversial subject matter of her book (a sex transition). On a positive note, Kristen Anderson-Lopez—a musical theatre colleague who went on to write the sound track of the Disney movie Frozen— was incredibly generous, and provided a beautiful blurb for my cover.

So there you have it. At the moment I’m curating a collection of my short stories to send out. But I’m also getting ready to write another book. If I do, and am lucky enough to get it published, I will be much wiser the next time.

Alison Hubbard invites readers to reach out with questions or comments to alisonhubbardauthor@gmail.com. She says, "I don’t have all the answers, but am happy to help."

The Kelsey Outrage is available from the usual online suspects like Amazon as well as from Bookshop.org, the online store that shares profits with brick-and-mortar stores.

mechanics: replace

The “replace” function can be a powerful tool for fine-tuning a text. (In Word, it’s under “edit” on the formatting bar. There are a coupleof ways I like to use it, and if I am in early enough on a manuscript and the author is open to my input, I often recommend they do it themselves. (When I amfortunate enough to have work at all (wink-wink).)

First, “replace” can identify clusters of is/are/am/been/was/were verbs, the words a more innocent age labeled as“copular verbs.”. Nothing wrong with any of these words, but probably you want to be aware if they are massing anywhere. Rewriting with a stronger verb can oftenimprove a sentence. Plus, every passive sentence contains one of these words, and probably you don’t want to dwell too long in passive-voice land. (Yes, passivesentences are necessary. They are especially useful if you or your character want to avoid stating the sentence’s subject. Richard Nixon: “Mistakes weremade.”)

So here’s how. Replace each of these words with boldface. (I like to go a chapter at a time.) Now you can spot densely-populated regions byjust swimming your eyes over the pages. I wish I had thought of this 40 years ago. The first paragraph of the liner notes for that Glenville recording stillhaunts me.

One of my weaknesses as a writer is an occasional over-fondness for long sentences. To identify passages where I’m channeling myinner Faulkner, I replace every period with a couple of paragraph symbols. Since I’m already adding space after each paragraph, this makes every sentence clearlyannounce its girth. To do this in Word: From the “home” tab, go to “editing” (the little magnifying glass), open “replace,” then the “special” menu. Hereare all the formatting commands. Just put a period in the “find what” field and a couple of “paragraph marks” in the “replace with” field. All your sentencesare now isolated, and you can readily see any clusters of three- or four-line—or longer ones. Even though I feel like every one of my tumescent constructionsis a thing of beauty, I shed not a tear as I bust up gangs of them.

I also like to temporarily embolden “very,” and any other throw-away words I suspect may be lurking. of, that, really

Email me (editorwv@hotmail.com) if you have any comments on this or anything else. I have an opinion on nearly every topic. And tell mewhat you’re working on. Don’t send a sample, just a few words about your baby. I’ll reply with an encouraging sentiment or two.

Last book that kept me up literally all night: The Red Tent, by Anita Diamant. ISBN 13: 9780312195519

March 2024 Adventures in Editing with Danny Williams

In some police departments, trainees are required to zap themselves with a Taser. The idea is that, if they are going to be carrying this thing and potentially inflicting it on people, they ought to be aware of what it feels like.

With similar reasoning, I am now writing a novel and editing it myself. It’s only fair that I experience firsthand the kind of grief I visit upon my authors. (Expect a giant plot twist in this column, nine paragraphs down.)

The story comes from a character I developed for an author about 10 years ago. One of his people needed a lot more substance, so I gave the writer an example of a detailed backstory and personality. He didn’t like my idea at all, and he wrote his own. That’s a fine example of me succeeding at my job. I don’t know if he appreciates how my failure at improving his work led to improvement in his work. I kind of hope not. It’s fun to feel sneaky.

That left me with an unbooked character, somewhat fleshed out and ready to go. He’s an engineer in his early 60s. A car accident a few years back killed his wife and severely bunged up his left leg. Now he’s cynical and withdrawn. The “action” will be him making a few modest steps toward re-engaging with life.

I always overthink stuff. I enjoy it, and it’s harmless as long as I step back after all the thinking, and use the necessary parts and let the rest go. Now on to the timeline. I want the guy—Chris Weatherholt—to be an undergrad in the days when all the science majors carried 20-inch slide rules on their belts. The first scientific calculator was introduced in 1972, meaning the slide rules would have been necessary before that, and probably for a year or two after. I birthed Chris in in 1949, and enrolled him at Sandusky Polytechnic in 1967.

Location will not be a large factor, and maybe won’t even be mentioned, but I’m going with Ironton, Ohio. It’s not far from my boyhood home, so I know the territory. I can have a large-ish hospital, rolling hills, a river, a university 20 minutes away, and whatever other details I find useful, without needing to double-check everything for consistency. I’m not going to goof up and have the university an hour away in one scene, because I know it isn’t.*

Then a classic overthink, deciding how to deal with Vietnam. Chris turns 18 at the height of the war. Did he serve a couple of years? Join ROTC? What? When my brain returned to reality, I realized it doesn’t matter now.

After I got 1949 as a beginning, the rest of the timeline was not that difficult. If he’s early 60s, 2012 works. I gave him a grown daughter, and decided she’s 28, and living and working in Minneapolis, making her a 1984 baby, when Chris was 35. That works out. There’s room for an older child, or even more, if I decide that would be helpful. He could also refer to a previous marriage. Plenty of time to get out of marriage one, recover a bit, remarry, and become a dad at 35. I’m putting the fatal and crippling car crash four years previous. I believe his daughter and friends would be telling him it’s time to let it go a little. I want him to be able to drive a car despite his injury, but have a quite difficult time walking or climbing stairs, and I want his mobility impairment to worsen with time. Sadly, I have a dear friend I can model this on. (About the most cheerful, positive guy in the world. Working together at a playground, we used walkie-talkies. He called his a limpie-talkie.)

Some stuff is still not resolved. I want the story to occupy about one year, so at some point I’ll probably want snow, school graduation, fresh tomatoes, or something, and the months will fall into place. (I’m a stickler for that. Long ago one of my victims authors tried making ironweed bloom too early in the year. Count on me to spot details like that, Sometimes I’m saving an author from an embarrassing goof, and other times I’m being an obsessive buttache.)

Now for a fatal self-inflicted wound. Inspired by the inspired writing of Love Palace, I decided to give my guy a voice kind of like Martha’s—cynically playful, self-consciously inventive and erudite—and let him narrate his own story. Reading Meredith Sue Willis’s work, it seemed like a pretty easy way to go. Yeah, and Joe DiMaggio famously made center field look pretty easy, too. He never had to run or dive, all the balls came right to him. A couple thousand words in, I realized I’m not a DiMaggio or Willis, and I would not be capable of controlling Chris’s language for 90,000 words. I asked him to look on life with ironic amusement, but he kept drifting into flat-out comedy.

I’ve begun an alternative novel instead. Stupid, maybe, but the family I was visiting with in Florida the past couple of weeks said that their previous house guests went tent camping in the Everglades, so I’m not way out there on the right-hand limit of the stupid spectrum. My new plan is to work this other novel to completion or near it then bring back Chris, but let an anonymous narrator relate the story. I’ve written a few episodes of the relief novel already, and made notes toward a few more. By this time next month, I will have 30,000-plus words on imaginary paper. Maybe.

*Check out Naked Came the Stranger, a 1969 literary hoax in novel form. As a spoof of what they perceived as an American appetite for over-the-top sex in a novel and no concern for literary merit, a group of writers created an intentionally bad but sexually explicit work and published it under the name of a single author. The writers agreed on the names of characters and little else, and wrote chapters without collaborating. The result was a ludicrous mess of writing. For example, one woman’s nude body was bronze in one chapter and alabaster in another. But it was nude, that’s what mattered. The book validated the authors’ point. Sales were brisk, and readers apparently did not know or care that they were being made fun of.

Watch your language!

Electronic Arts, a maker of video games, miscalculated, and needed to can about 670 of their workers. In the press release announcing this, the company said the “streamlining” would “deliver deeper, more connected experiences for fans.”

The PR term for this is “spin,” but we all know the correct word is “crap.” And not even amusing crap. The father (maybe grandfather) of a character in Cormac McCarthy’s Child of God was publicly hanged for murder. Telling about his father’s death later, the guy would say his father “was taking part in a public occasion, and the platform gave way.”

“ . . . while a soaring lobby across the top will house restaurants, bars, an art gallery a glass-floored (and glass-ceilinged) viewing platform and — should a license be granted — a subterranean casino.” ‘(nyt)

No, the soaring lobby across the top will not house a subterranean casino.

Headline of the month:

Trump Lawyer Argues ‘Appearance of Impropriety’

Is Enough to Disqualify Prosecutor – (nyt)

We don’t want any appearance of impropriety here, do we?

“She didn’t believe it until she found the $600 bill on the table.”

From a news story about a waitress receiving a huge tip.

“Payl Feig and his baroquely profane star, Melissa McCarthy . . . ” nyt

Brilliant! Baroquely profane. Mating two words which people don’t usually expect to see together can create so much more meaning. I once wrote that a festival which celebrates Appalachian music and strictly prohibits bluegrass and other modern genres was “aggressively traditional,” and had to arm-wrestle the magazine editor to prevent him altering it to “steadfastly traditional.” My way says a lot more.

One current speech habit which mildly irritates or amuses me is beginning every locution with “So,…” So I searched, and found I had used “so” 26. Too many times in 1,500 words, I believe. So I fixed it, got it down to 6. In my old typewriter days, I would almost certainly not have noticed, and if I had, I would have groaned and left it rather than retyping. Also caught a redundancy, “about 120 or so,” and deleted “or so.” Sometimes this job really is easy.

“Watch Your Language” book review. Edwin Newman, Strictly Speaking, 1974. A roundly condemned book, and rightly so. It’s prescriptive grammar, lamenting that people nowadays don’t talk right, and urging them to start. In my mind, I totally agree. My late lamented Sally Ann, best dog ever, would bark and snarl if anyone told her to “lay down.” If you wanted her to lie down, you needed to tell her that. I practice a great many bygone “correct” language conventions. But I know better than to publicly urge others to do so. Language is a living thing, and there’s no cryogenic lab large enough to freeze it. But Newman made a second point, that news people, in particular, are prey to adopting and spreading lazy or pompous habits. Written and verbal news reports invariably referred to the president of Argentina as “Juan D. Peron.” “Presumably,” Newman writes, “this is to avoid confusion with Juan Q. Peron, who is also the president of Argentina.” Newman proposed creating a special award for news people who manage to not, after a major triumph of some sort, ask the winner, “How does it feel.” (Like we need to hear some athlete, pulse still racing, try to piece together synonyms for “good.”) Or entertainment reporters who go a week without using the phrase “taking . . . by storm.” That’s still a phrase most often used automatically and thoughtlessly, and these days we have the related “go viral.” In both his misguided appeal to “save” the language and his eternally valid appeal to avoid mindless writing, Newman’s adjuration is simple: Watch your language.

Attempt at a pickup lineWant to see some examples of Chris Weatherholt going off track with his narrative voice and wrecking my embryonic novel, or a page or two from my hastily substituted alternate novel (warning: contains graphic stupidity), or a completely crafted scene or two which might or might not fit somewhere into something some day, or a currently in-process short story which I intend to be highly humorous? Show me a little of yours, and I’ll show you mine.

Danny Williams, editorwv@hotmail.com

Adventures in Editing, February, 2024

Danny Williams

editorwv@hotmail.comIt's a great time to be me right now. I've been actually editing an actual manuscript, for an actual author, who sends actual money. Despite my plus rep in the business, including Meredith Sue calling me her Featured Editor and saying the work I did as editor of one of her novels was Terrific, traffic has been slow. But this one author has hired me, and the job will go a ways toward filling the money hole left by our new furnace.

The novel is one I would choose to read. Not that it matters. I'm providing a service, like a house painter. I'll take pride in doing a beautiful job on your house, whether I personally would like to live there or not. I probably would not choose a big, fat, intricately detailed corporate history of a pioneering high-tech business from my Boring Book Club monthly flyer, but it was a blast to edit, and it added to my already-fearsome trove of useless knowledge. But, on to my job.

"Before We Left the Land" is a simple story. Not necessarily as a reader, but as an editor. It's America in the 1940s, with no flashbacks, fast-forwarding, foreshadowing, or supernatural creatures or events. There are no words or concepts I needed to look up (though I enjoy that).

It is a multi-generational family in their semi-rural ancestral home. Semi-rural because there's a modest city a half-hour away, and the road to their house is passable most of the year--to beat-up farm trucks, anyway. The house has electricity and a refrigerator, one neighbor has a telephone, and another has a non-truck car. The winds of change have begun wafting into their century-old lifestyle, and--and this is the book--a tornado is coming. As in most aspects of American life, 1950 will be beyond the imagination of 1940.

I couldn't think of one major large-scale thing to recommend to the author. The structure and pacing are sound, the dialogue crisp and natural (unnaturally natural in one masterful scene of a few friends getting drunk and ragging on each other). My most substantial edit to the narrative was in the account of a baseball game. The game was important to the tale, but the author is apparently not a fan.

I place commas by ear. I read a manuscript aloud to myself--away from my wife--and I can hear the commas. In the sentence above, I do not hear "apparently [comma] not a fan." So suck on that, auto-suggest.

If you know my work (and you really ought to) [comma] you can predict I got all over the pronouns. If there's any way the reader could misattribute a pronoun, I want the antecedent there. A favorite from an IMDB summary: "A naked man with a gun points it (the gun) at a woman." Some wise editor inserted the reference to the gun because a reader could possibly be confused about what the naked man was pointing at the woman. I get somewhat obsessive about this, and authors quite rightly reject many or most of my edits. That's a win for the author, being prompted to take one more look.

Many of my edits are to my edits. Two characters take a car trip from north-central West Virginia to Tampa. The author doesn't say enough about it, just kind of says they were one place then they were the other. I found out that US Route 19 was open by this time, and went all the way. It would have been a trying journey, with town and city stop signs and traffic lights, gravel sections of road, poorly-marked changes from the route being constantly shifted, livestock crossing the road, and such. I wrote a couple paragraphs worthy of the delightful Bad Trips, a sampling of amusing or terrifying travel-gone-wrong writing. When I stepped back and looked, I had tilted the chapter out of balance. So I took it back, and with a sentence here and a phrase there, the author simply made sure the reader understood that the two arrived in Tampa tired, sweaty, and thoroughly sick of each other.

An aside, in praise of the author: The men received sobering news in Tampa. On the trip home, the two long-time antagonists came to some small understanding and appreciation of each other. Nicely done, unnamed author!

I also trim unnecessary words, even though a lot of unnecessary words are in fact necessary. Nobody wants to read a book consisting of telegrams. [Un-old people, ask a grayback what a telegram was.] But, like with the pronouns, it's a good thing when the author looks at an excision and decides I am wrong. Somewhere above in this missive, I wrote "one of the neighbors has a phone," then tried "one neighbor has a phone," and decided I liked the shorter version better. If you like the longer one, that's cool. Really.

Also--and here's a clue to my level of business acumen--I'll share some steps you can take to lessen the amount of work you need to pay me for. Somewhere on Meredith Sue's site, I've placed a suite of "Search and Replace" maneuvers. This One Weird Trick! will expose the bones of a manuscript, and let you quickly make some editing decisions I might have really soaked you for. And there are others.

So, a fun month for me, but now it's over. Get hold of me and let's talk about your baby. Even if it's a big, fat, intricately detailed corporate history of a pioneering high-tech business.

Notes.

According to The Chicago Manual of Style, which costs so bleeping much we feel like we ought to follow it, a published book gets set in italic, and an unpublished manuscript gets quotation marks. Why? Because Chicago, that's why.

Keath Fraser, editor. Bad Trips: A Sometimes Terrifying, Sometimes Hilarious Collection of Writing on the Perils of the Road. (various editions) Passages from works by Umberto Eco, Anita Desai, Jonathan Raban, David Mamet, Martin Amis, John Updike, and others.

***

Fun exercise for writers, from an NYT article:

Wasn't billed as about writing, but we know everything anywhere is about writing. For a short period, like 10 or 15 minutes, just write down what you see, hear, smell, or feel, in a barebones way. So here's my unedited scrawl from 10 minutes in the Blue Moose downtown.

Sweatshirt: I Look Better Bent Over.

Big, athletic-looking lady, maybe 20-something, much piercing. Shaved head except long, straight hair in back and a blue tuft and a pink tuft in front of ear, poofed over glasses arm. Pink and blue swirly-colored Crocs.

Mild house music.

Four teenage girls chatting happily.

Hot water in the hand sink is very, very hot.

Two-tone orange paint in bathroom.

Large, maybe 3x5 feet, blackboard with detailed, artfully-done menu.

Occasional ice-in-the-blender sound.

4 men in a Mustang convertible, top down.

NJ car with bumper sticker "Using Your Turn Signal Is Not Giving In to the Enemy."

***

Headline of the Week, from the Charleston Gazette:

Book Reviews for Writers: Danny Williams on Meredith Sue Willis's Love Palace

In this “book review for writers,” I plan to bypass much of the usual book-review matter, and look instead at what the author is doing and how they are doing it. This may or may not be of use to someone, but for me, reading a book from this new angle has been fun and instructive.

Love Palace, by Meredith Sue Willis, is a Meredith Sue Willis novel. She’s written a boatload of them, and covered quite a range of action, setting, and characters, but from time to time she comes back to a familiar place.

In this type of Willis novel, setting and action retire to the background. The time and place are familiar. Modern amenities exist, the location is urban or suburban, but there's no strong tie to any particular location or time frame. No Eiffel Tower, Windows 9, side-ponytail fad, Grand Canyon, Barbie movie, or Biggest Ball of Twine in Minnesota. The central character is a woman, not especially old or young, who’s facing some challenges or decisions. She is intelligent, more or less articulate, and likeable, but maybe not loveable. Her situation might be unusual, even extreme, but it’s recognizable and relatable to readers. There are a very few other important actors, not enough to muddle the story or distract attention from the star. Minor characters all have some function, some reason to appear on the stage. If Hollywood makes a movie of one of these novels, there won't be any need for elaborate costuming and makeup, stunt doubles, exotic props, or on-set medical facilities. There are no fistfights, alien beings, explosions, whalebone corsets, weapons of mass destruction . . . not even one little car chase. Within all these parameters, about the only way left to advance the story is to put the characters together and see what they do.

And so to Love Palace. Martha narrates the novel, which means it's first-person writing, which means it's all about Martha and her encounters with herself and other characters. Chief among these are John, a slippery sort-of spiritual leader/political organizer/compulsive womanizer, and Robby, a 21-year-old man eager for something or other. The small cast also includes Martha's sister, her therapist, and an assortment of characters at the Love Palace, a sort-of church/community-action center/flophouse in a blighted urban section where upscale development looms over the lives of the remaining residents. The building is a former adult entertainment venue. The new occupants removed the "A" from the facade and attempted to redub it LOVE P LACE, but of course that didn't work out.

Martha resembles a few of Willis’s other protagonists. She’s a woman, neither young nor old—43 in this case. She’s facing some challenges, internal and external, but there’s no immediate threat to her life or health. Some aspects of her makeup or her situation may seem extraordinary, but it’s only an issue of degree. Her issues and her reactions to them are part of humanity. Some life changes are surely coming, and by the end of the novel she’s likely to have a different daily life and a different relationship with herself and others, but she will be the same Martha. There will be no transfiguration. This is Willis, not Dickens.

Well if Martha’s the narrator, that means Love Palace is first-person, and that brings a special set of considerations. In my own fiction writing—rarely more than a few hundred or a couple thousand words, I’ll admit—writing in first person is in one small sense mechanically easy. There’s no consideration of what other characters know or don’t know or what they may be thinking, so the writer doesn’t need to decide how much of that to include, and where and how.

In first-person narrative, the writer’s task is constructing the narrator’s personality through the character’s use of language. Here’s the hard part. The reader will be trapped in an elevator with this person for the duration. If we don’t on some level enjoy the way this person talks, we will start looking around for an escape, and likely find that the only way out is to put down the book for “later.” And we need to find out who this person is, but this needs to happen gently, piece by piece. If the narrator begins reciting an Apologia Pro Vita Sua, we’ll soon be eyeing the little access hatch on the elevator’s ceiling. Willis has committed to having Martha narrate Love Palace, so now the task is to tell us everything, but without sounding like she's working at it.

So what does Martha's voice sound like? Playfully intelligent. Amusingly self-deprecating. She’s well aware of her shortcomings, overindulgences, challenges, and self-defeating behaviors, and she thoroughly enjoys a cynical laugh at herself. Maybe she places her problems too close to the center of her self-identity, and unconsciously holds them dear. Her first words to us are “I had a meltdown after my birthday.” Seven words into the novel, and already we know we've met a woman who's capable of observing herself, and who intends to involve us in the process.

Here are some more bits of Martha from the first eight and a half pages of Love Palace, the first chapter.

During the years of the longtime boyfriend, who I call Rotter the Third (Rotter two being my divorced husband and Rotter One being my father) . . . I’m good in bed, too, by which I don’t mean particularly skilled, just happy. . . . There is something really satisfying about sinking to the bottom like this. . . . Rotter Three decided that, unlike his hedge funds, I was not increasing in value. . . . There was a pretty up-front competition in my therapy group over who was most self-destructive. . . . My God he’s dumb, I thought. Unless it was Thorazine. . . . I could feel my neuroses clearing away like a stuffed nose shot up with Afrin. I could feel the breezes, I’d take a poetry workshop. I’d get a job counseling teenagers. . . . Dr. Landowska says there are worse reasons to have sex than to feel beautiful, but there are also better ones. . . . like a lot of what Dr. Landowska says: practical, true, and way beyond my power to put into effect.

There’s a lot of personality there. Martha very much wants to tell us about herself. She’s not harshly judgmental of people different from herself, but she does feel at least a little superior. Superior to the Rotters, certainly, but also gently superior to “ordinary” people, like the ones who actually believe in traditional avenues of self-improvement like poetry or satisfying employment. Her affected wordplay tells us she is unusually intelligent and deeply creative, and she puts effort into the game of words and ideas. “Rotter.” Probably the immediate word would be asshole, jerk, or maybe fucker, with rotter way down the list. Willis enables Martha to educate the reader about herself, and deftly do it like that teacher who was such an engaging person to spend time with, you didn't realize how much you were learning until after class.

Willis conscientiously maintains Martha’s playful language, whatever the topic. On her aged, infirm grandmother Martha’s pronouncement is grimly playful: She wasn’t dead yet, just warehoused at Miriam Sisters. (47) At a Chinese restaurant: It had been the China Tea Cup for about a million years, and then then when the area began to come up, they remodeled and started cooking their actual original native cuisine, which they remarkably remembered how to cook after all the years of chop suey. (95) Out of place at a posh restaurant, she tells the wealthy man who has invited her, “You order, I’ve always been a good eater. I’ll eat anything higher on the food chain than beetles.” (128) Assessing the current trend in cars: Parked in front of the Love Palace was an enormous silver block of an SUV with one of those aggressive names like Colossus or Incursion. (188) These examples are in page order because I found them by casually flipping through the book and looking for an apt sentence wherever I landed. Martha’s voice permeates nearly every page.

Of course, some things are happening outside Martha’s mind, in the so-called real world. She has revealed that she’s broke, about to lose her apartment, unemployed, and not really looking for work. She seems unable or unwilling to plan and accomplish anything. Poverty has reduced her diet from spaghetti with canned sauce to spaghetti without the sauce. But she still has enough money for some day drinking at a local bar, and as she sits staring at her reflection between bottles in the big mirror behind the bar, pretending to look at the want ads and blithely wallowing in her impotence, she seizes an opportunity to exercise the one power remaining to her—the power to attract men. At the moment, the nearest potential conquest is a cute man less than half her age. The man wants to tell Martha about Jesus, so their conversation bypasses the usual phatic phase and goes straight into substantial matters. When it turns out the man is a virgin, the possibility of bedding him appears epic, enough of a triumph to jump-start her life. “I decided that if I could get Robby to come home with me, my luck would change. I would make the phone calls. I would have a job within a week. . . . Get rid of the five pounds I’d picked up, and be so self-confident and svelte . . . ”

Playfully exaggerating of course, but Martha does actually attach some authentic power to the act of seduction. And here's an important piece of Willis's art. Martha's first real action in the novel reinforces our understanding of her character. Willis could have had Martha tidy her apartment, apply for a job, buy some groceries, call her sister, or any number of deeds, but those would have been a time-out from our education. Martha's attractiveness as validation of her self-worth--and her genuine enjoyment of sex--are part of her, and part of the journey the reader will be sharing with her.

And it sort of works. Through Robby, Martha gets a sort-of job, organizing the neglected office of the jumbled mess of the Love Palace. It’s a fitting site for Martha and her vague, shapeless notion of who she is and where she’s going, combining fragmented elements of a church, flophouse, neighborhood action committee, cult compound, soup kitchen, and love nest. Bringing some order to the chaotic office reminds Martha that she does possess some ability besides seduction. She makes a beginning at throwing out papers and organizing others into piles. She plunges into sorting out the haphazardly kept finances. When she learns that the new-looking dishwasher doesn’t work and nobody seems to even wonder why, she finds the manual, calls the 800 number, learns that the machine is under warranty, and gets it fixed the same day. She tells her therapist, “At the Love Palace I haven’t even started, but I already feel good, competent. I go diving into the piles of papers for a phone book and find a wallet that belongs to one of the girls. They think I’m a genius. . . . I could do a dozen things before Robby and the others even got up in the morning. I felt a glow of competence and superiority.” (60-62) She even goes some brief time without seducing a man or allowing herself to be seduced by one.

So now instead of directly letting us learn more about Martha, Willis is letting us watch as Martha learns more about herself.

Martha doesn't revel in her superiority. She flashes it, mentally checks the box, and moves on. A long-ago college English graduate and apparently a lifetime reader, she likes to drop an apt literary quotation or reference into a conversation, no doubt aware that few if any in her circle are conversant with Shakespeare or Tolstoy. When nobody seems to notice it, she happily moves on instead of calling attention to the little boost she's given herself.

The more time we spend with Martha, the more we see the essential wholeness behind her at times puzzling behaviors. Early in her Love Palace tenure, Martha discovers that someone is making ATM withdrawals from the agency’s bank account, a couple hundred dollars or so at a time. Trying to learn what’s going on, she finds out nobody even knows how many ATM cards exist, or who has them. Martha continues to probe the mystery over the course of probably weeks. Wouldn’t anyone just go to the bank, cancel all the cards, and wait to see who shows up asking for one? Confident that Willis had thought of this, and Martha’s failure to take this simple, obvious step was somehow rooted in who she is, I held that thought as I read on. Eventually I realized that, of course, Martha is enjoying the heck out of this. Delving into old papers, suspecting this or that person among the raggle-taggle of the Love Palace, discreetly questioning people, exercising her intelligence, placing herself as the person with the power to examine the others—this is Martha’s playground. Willis never attaches many weighty adjectives to Martha’s character, but by now we know her well enough to integrate a seemingly absurd behavior into our understanding of who she is.

The truth emerges, other matters arise, and characters not mentioned here play their parts. These will be addressed in more typical reviews. This review for writers is about how Willis contrives to make our entry into Martha’s life feel as natural and spontaneous as the relationships we’ve played out so many times before, in real life and in other skilled and insightful fiction.

When we say goodbye, Martha is in a quite comfortable position . . . for her. Her job is certainly not long-term, and she will likely lose her apartment soon. She may or may not be sort-of married (it’s complicated, of course). She’s had a couple of unexpected sexual flings, has no immediate plans for another, but that will happen. Importantly, she has discovered she can accept and even embrace her unorthodox makeup, and survive and even in some small way thrive without plans or directions, finding some foothold wherever circumstances land her. Willis has made Martha real for us, and we would like to know where she goes from here. We wish her well.

Got a nice novel manuscript in the shop this week. Has some mildly magical elements—something more than natural, but way short of dragons and crystal balls.* About half of it is set in 1860 or 1861 Virginia, on a quite wealthy horse breeding, trading, and racing concern. It’s very carefully written, and even with my nearly pathological attention to detail I couldn’t catch the author in a timeline slip or a substantial tense shift or anything.

Most of my advice was to take greater advantage of the setting, an opulent estate in the final years of the Virginia slave economy. There was a magnificent plantation mansion, and gala feasts and dances. Don’t just say the woman was dressing for dinner, tell me about her gown, bustle, wig, or corset. The gaily clad menfolk, too. And that feast—what’s on the table? All the bounty of farm, ranch, orchard, and sea are withing reach, so tempt me with some. And that opulent mansion, I want to hear about its colonnaded veranda, English oak woodwork, and manicured landscape.

The author had written some nice old-time-sounding dialogue, and I encouraged him to do more. Many of the suggestions I’ve actually learned in my academic study of Appalachian speech, which differs from modern Standard American English largely in its retention of obsolescent syntax.** Adding essentially meaningless auxiliaries to verbs: I might could do that. Other quaint redundancies: I like these ones. Using “anymore” positively, and “of” with times and seasons: Anymore, I like to sleep later of a morning. And one character was visiting horseman from Louisiana, so I would give him a little belle femme, merci, excusez moi, and à tout a l-heure.

Speech idiosyncrasies can add differentiation to dialogue. An individual might be prone to throat-clearing before speaking, cursing, or substituting long or obscure words for simple ones. A former co-worker ended every sentence with rising pitch, so every utterance sounded like a question. Nowadays, in every group of speakers there’s probably one who begins every remark with “so.” All these tools are obvious, but it requires awareness and effort for authors to prevent dialogue from sounding like their own.***

Maybe my input will prompt the author to reexamine the manuscript, maybe not. I honestly do not care much. This work brings me joy.

* Paola Corso, Giovanna’s 86 Circles and Other Stories. Twenty-some years ago I had the pleasure of reading the manuscript of this collection. Ms. Corso's habitual setting is urban Appalachian, a much under-recognized genre, and many of these stories feature just this type of quasi-magical touches. Sadly, in the end I was denied the opportunity of working with this gifted fiction writer, poet, and photographer. University of Wisconsin offered her a quite modest advance, and my tightwad director would not allow me to match it. (No budget concerns on his pet projects, of course.) Anyhow, read this, and more of her work, for enjoyment and for instruction.

** Walt Wolfram and Donna Christian, Appalachian Speech. After all the years and scholarship, this slender 1976 opus is still the place to start on Appalachian (or other old-timey) dialect. Quite possibly it will be as far as you need to go with the subject, sparing you some of the more ponderous tomes.

*** Must mention Ken Sullivan, former long-time editor of Goldenseal magazine. He had a real knack for taking submissions from all types of informants and somehow doing a great job of editing while keeping the writer's individual voice. I try to keep him in mind while doing my own work.

Send me some of your stuff—vague notions or developing manuscripts. I'll put a couple hours into checking it out and giving an opinion, for free. I would do every editing job in its entirety for free, except that I'd get so immersed I would have no time for cleaning the bird cage or showering.

Danny Williams, editorwv@hotmail.com

(see one of my other personae at Facebook Page "Sassafras Music Shop.")

Names in Fiction

by Danny Williams

People’s names are a big deal. They’re such a big deal that—except for ms. lang and mr. cummings—they begin with capital letters. When someone tells us their name, we try to remember it, and sometimes feel guilty if we don’t. Here’s some stuff I think about names in books, from my reading and editing.

In most stories, I believe awarding a character a name ought to be a special recognition, like giving a letter to a school athlete. Just like in the putative “real” world, we can’t help but take special notice of someone’s name. If the character is just passing through, never to return, giving them a name is asking the reader to spend a tiny bit of effort on something that in the end doesn’t matter. We’ve all had that boss. Give your readers a break. Back to a Maugham sentence I remarked upon before, “The doctor was a small, beardless man with a dismissive air.” Besides painting a sharp portrait with a very few words, the sentence tells the reader, “It’s okay to forget this guy. He won’t be back.”

As for what to name your people, you can figure that out. Time and place are important. If I were setting a realistic story in my youthful days in Wayne County, West Virginia in the 1950s and1960s, there would be no Gonzales or Nakamura, no Pierre or Mercedes. Year after year I sat between Linda Watts and Debra Witham, and I believe Lindas and Deborahs made up about half the girls in my class of 1970.

One of my writers, who admits he does not read, populated a government research facility in Northern Virginia with names which would have fit right in with my childhood. I talked him into a Mustafa, a Devonte, a Negrescu, and a few others. He had a Dick Dangerfield he would not part with, but I nudged him into making the man kind of a wimp. (Dick also complained continuously about the humidity in his basement office, so I suggested to the author that the man might enjoy growing bromeliads.)

And with Dick Dangerfield, we come to characternyms. (I made that up.) Besides choosing a set of names appropriate to the setting, you could decide to use names which say or suggest something about the character. Annie Proulx (author of my favorite Appalachian novel, though it is set in Newfoundland) uses this tool for central characters in much of her writing. Homer Quoyle feels like he doesn’t fit in anywhere. Loyal Blood is tragically upright. Bob Dollar manipulates down-on-their-luck farmers into selling their land. An unfaithful and abusive wife, Petal Bear, tries to sell her daughters, Bunny and Sunshine, to sex traffickers. Dolor Gagnon is a very sad man.

Unless you’re writing a children’s book or a fantasy, the decision to go this route is a big one. Some readers will absorb the name into their perception of the character, and others (raising my hand) will probably find it distracting, maybe fatally so. If you can’t resist the fun of it, you might apply the name to a relatively minor character. A barrister named Mr. Bideawhile appears in a few Anthony Trollope novels, and a fabulously rich nobleman, the Duke of Omnium.

As a final check, along with the dozens of other final checks, just list all the names in your story. One of my very good writers found she had named four characters with forms of William. One of them was so minor he could be anonymized, and she redubbed the others.

I love big fat novels, ones so thick and dense the author has to supply a list of characters. If you write one of those, then obviously much of what I just said does not apply. Also, tell me how to get a copy.

React to this post, tell me about your current project, send a sample, or even talk about us working together. Or anything else. I have an opinion on every topic. Also, I have written a chapter of yet another imaginary novel, and I would adore some feedback from y’all. Show me yours and I’ll show you mine.

Danny Williams

“An editor should have a pimp for a brother, so he’d have someone to look up to.”

–Gene Fowler

From Middlemarch George Eliot From The Mill on the FlossFive Lessons from George Eliot:

Celebrating Her 200th Birthday 11/22/1819

(With writing exercises)If you don't know the story of George Eliot's life, it is worth a novel in itself: her religious rebellion; her unconventional

twenties as a single woman trying to earn a living editing and translating; how she finally met a man who fully supported her work, but could not marry her because of what now seem like ridiculous divorce laws; how she and he considered themselves married by their own commitments and morality; how the rest of the world did not; how she became one of the most famous and morally influential writers of her century. Indeed, a lot of us believe that her novel Middlemarch may be one of the five best novels ever written in English.

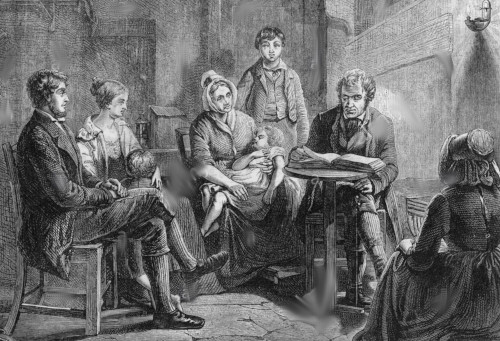

You may or may not have the patience for the long descriptions and pontificating of nineteenth century fiction, but if you haven't read George Eliot, at least give her a try. A good place to start is The Mill on the Floss. It has a feisty girl protagonist whose fatal flaw is that she wants too much to be loved, especially by her honorable but rigid and self-righteous brother. It paints a splendid picture of life in rural England in the first half of the nineteenth century and has a satisfyingly melodramatic climax (see illustration).

But Middlemarch and The Mill on the Floss are recommendations for reading. What does Eliot have to suggest to us about writing?

Lesson I:

This first lesson is not exclusively from George Eliot, but rather from all the best nineteenth century novelists (the Russians, the French, certainly the English). These writers believed that everything can go into fiction. Nothing is forbidden--not teaching moments or philosophical speculations. I strongly recommend that at least in your first draft, you should reach out broadly. Don't hesitate to include religion or current events or scandals of the day along with the close-focus of physical detail and internal experience. Include dreams and recipes and baseball box scores if the spirit moves you.

This is not, of course, to suggest that you write a story strictly to push a particular political or religious belief. That isn't fiction but rather journalism or an op-ed piece. The point is that these are part of real life, and prose narrative in its many ways tends to be about real life--even when it is fantasy or science fiction or horror.

I consider it enriching to your fiction to give a character some of the doubts and queries that may run through your own mind. You can do this in monologue or dialogue. Sex and violence and descriptions of weather and meals are all part of fiction, but so may be discussions about politics and work

One of George Eliot's novels, Felix Holt: Radical is set firmly at a time of labor unrest in England. She was interested in how a change in the law (the First Reform Act of 1832) would affect workers and farmers as well as in the terrible secret of one of her characters. She sometimes goes off on not-so-little tangents that show off her learning (probably in more detail than a twenty-first century reader appreciates), but the point here is that you can use everything in even a lean, minimalist story. Put the events or ideas in dialogue or have a television in the background of a bar. Have your main character mull over the big issues as we sometimes do in real life.

Exercise 1: This is another of those all purpose exercises for restarting a stalled story or book, or to get more material. Have your main character hear something on the radio or see something on TV or on the smart phone, some world event or famous crime. You can use this to ground the story in its time and place (which impeachment hearing is this?), but more importantly, What does it mean to your character? How does the character react, if at all? With anxiety? With cynicism?

Exercise 2: Think about the media your characters are using. Are there thematic news stories that can add to the mood and ambiance? If your story is set in 1976-77, for example, how do your characters react to the Son of Sam serial killings?

Exercise 3: Rather than have your protagonist react internally to the events, have them come up in conversation before class, at the dinner table, etc.

Lesson II:

Eliot is famous for her awareness of and appreciation of farming and the lives of farmers of various social levels. One of the things we often leave out of our fiction is work--that is to say, what people do day-to-day. Obviously you don't just write little essays about how things are done and set them in the middle of your fiction undigested, but anything in which you have interest or expertise can enrich your fiction. It may lead to some plot element, or it may lead to a deepening of the main character or a minor character. Phillip Roth has wonderful descriptions of glove-making in American Pastoral. It is part of what his main character does in his everyday life, and it eventually takes on symbolic meaning.

Exercise 4: Have a character watch her grandmother make tortillas (or do some other work with the hands): break down the physical action, mention the rich odor, the slapping sound. Or, give a character a job as a car salesman--What are the little tricks to keep up the customer's interest. Does the character like the challenge or hate the job? In other words, include your characters' professions or jobs.

Lesson III:

Eliot tends to use the omniscient viewpoint. She uses it very well, as do many of the nineteenth century novelists, but she always stays close to one character long enough to capture the full emotional depth of what that person is going through before pulling back to an overview or the next character. This is the essential challenge with the omniscient viewpoint. It is too easy to move around too much, creating a kind of narrative vertigo. Be sure you stay with one character long enough to learn something about him or her.

Exercise 5: If you are working with the omniscient viewpoint, experiment with following some peripheral character and following them very closely for a while--longer than you might without the special instruction. Choose a figure that almost disappears in the background. Maybe it's a dark gray city rat with a broken tail hurrying to the drain with a piece of pizza. Once you start following the rat, let us feel its struggle with the big piece of pizza. Is it a mother with hungry pups? How does the world look at drain level?

Lesson IV:

Our most vivid sense impressions probably happen when we are very young. This is one reason people often write successfully about their own childhoods. When we are small, many things are Firsts, and our senses are open and sharp. George Eliot wrote till her death about people in farm landscapes similar to the one she grew up in.

I'm not suggesting you suddenly put a toddler in your story (although that might be fun to see what happens) but rather that you use your characters' senses with the vividness of a child.

Eliot's probably least popular novel today is called Romola, and it is set in fifteenth century Florence. I didn't like it the first time I read it--I could feel her research weighing down the story, I thought. But then I read it again years later, after I actually visited Florence, and it suddenly lit up for me. I had my own sense impressions of the place that added to the book. I was also older, and the book's strengths are its portraits of traitors and turncoats: it isn't a cheerful book.

So the lesson is the importance of vivid sense impressions for making our fiction alive for ourselves and readers. Whether we've got a detective being beat up by bad guys or a child tasting bread hot out of the oven, we will go deeper into our created world and bring readers with us when the sense description is sharpest. Not longest, note, but most vivid.

Exercise 6: Go back to some scene you are having trouble with. Re-envision it with your eyes closed, starting with your senses other than seeing. Get some details of touch and the sensation of breeze or dampness in the air. What music is playing in the car down the street? What do you smell? Give these observations to one of the characters in your story, or just set the scene differently. Does it change what happens?

Exercise 7: Okay, try putting a toddler in your story! Maybe it's a child being smacked in a public place. How does you character react? Maybe it's a lost child, or the main character's family member. What does this stir up? Change about the plot? Daughters have become a cliché for tough guy thrillers and detectives. They are always getting kidnapped or threatened! You can borrow the cliché or try something different with the kid: humor? Disturbing a stake-out? Reminding the hero how much she doesn't want to have children of her own?

Lesson V:

Write what fascinates you, or don't bother. Eliot was through-out her life highly sensitive to criticism--pretty neurotic about it, really, to the point that her partner wrote letters to friends asking them not to send comments on her publications. She suffered during the process of writing a new book over how bad she thought it was, and dreaded reviews.

At the same time, while she accepted technical and stylistic suggestions, she always wrote what she wanted to. She had the good fortune to write in a way that led to great popularity and financial success, but she didn't seek popularity. She wrote to find out what her characters were really like, and she often surprised her readers, and possibly herself, about the depths of characters that in another writer's hand would have been caricatures.

For example. Maggie Tulliver's mother in The Mill on the Floss is a ridiculously superficial woman who is far more concerned about her beautiful linens and Maggie's unruly hair than about the child's moral or intellectual development. Still, as the story goes on, and after the family suffers heavy financial setbacks (and her beautiful linens have to be sold), she is faithful to her family, and more importantly, when Maggie suffers the the deepest social disgrace, she sticks by her.

Dickens would have handled it differently. He had one of the most amazing imaginations every employed in fiction writing, and his characters are so wonderful with their memorable tics and catch phrases, their inimitable names, extreme behaviors and large gestures. But in general, they don't change a lot.

Eliot, on the other hand, believed that the function of a novel is, among other things of course, to chart the gradual changes people go though from start to finish. She turns her characters before us as on a potter's wheel, gaining form, expanding here, narrowing here.