Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 196

April 20, 2018

When possible, read this newsletter online in its permanent location.

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

.

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 196

Coming in August-- MSW's latest novel, Their Houses!!

"Tough-minded, compelling...a terrific read" -- Phillip Lopate

"Sweet, slyly humorous cadences of West Virginia" -- Diane Simmons

"A compelling series of mysteries" --Jane Lazarre

Phyllis Wilson Moore has received the The Women of Appalachia Project (WOAP)'s 2018 Women of Appalachia Project (WOAP) Appalachian Advocate Award. Learn more here.

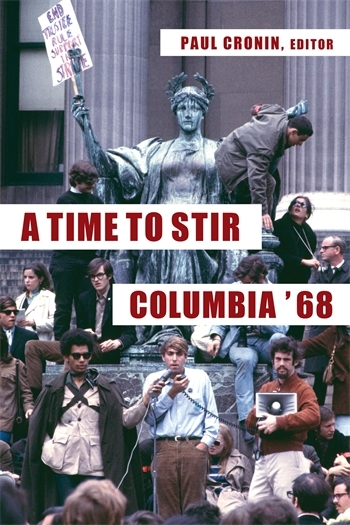

A solid left-leaning perspective and analysis by Eric Mann of events at Columbia University and beyond in the spring of 1968. Also check out A Time to Stir, from Columbia University Press.

Excellent publicity for Voices in Unity: Coming Together, Falling Apart, edited by Cat Pleska. The article is linked here from the Huntington, WV Herald-Dispatch was picked up by US News & World Report, The Houston Chronicle, Chicago Tribune, San Francisco Chronicle, the Kansas City Star and many more.

George Brosi writes reviews of books with Appalachian theme and perspectives. See below, and also visit his Appalachian Mountain Books site for more reviews as well as Appalachian events--updated monthly.

Contents of Issue #196

Books for Readers:

Various Books by Victor Depta

The Living and The Hunted by Matthew De La Peña

Democracy by Joan Didion

The Conformist by Alberto Moravia

A Book of American Martyrs

by Joyce Carol Oates

The Book of the Dead by Muriel

Rukeyser

Last Exit to Brooklyn By Hubert Selby, Jr.

William Tyndale: The Man Who Gave God an English Voice by David Teems

Reviews and Short Takes

Phyllis Moore's Revised Young Adult Appalachian Book List

Family Literary Games

With David Weinberger!

Follow up to Previous Issues

Things to Read & Hear Online

Announcements and News

Irene Weinberger Books

Anthologies of Appalachian Writing

The Appalachian region has been in the news this early spring with the the militant West Virginia teachers who went on strike and earned an improvement in their wages and health coverage, and with lots of debate and self-reflective coverage of the controversial Hillbilly Elegy (See Nathan Leslie's comments here). For a wide and deep way to learn something even more about this and all of the abundant literature of Appalachia, get to know the work, criticism, and activism of George Brosi.

Here at my new home, after nine months of fixing up and getting used to a new place, I am finally able to read again! As I wrote a couple of issues ago, during the move, I was only able to read narratives like Anthony Trollope or Michael Connolly's crime novels. I'm taking a break from Trollope, but still reading Connolly, a solid, clean stylist (MFA credentialed!), and his character Harry Bosch has an interesting back story (a murdered mother, highly stressful service in Vietnam). Harry, a homicide detective, sees himself as a kind of speaker for the dead on a mission to solve brutal murders.

For me, a major plus is that the Connelly books are mostly set in Los Angeles where my only son, only only daughter-in-law, and only granddaughter now live. I get a big kick out of Harry Bosch hopping on the 405 and then, when traffic gets too bad, going local. Bodies are discovered in all sorts of Los Angles spots: a park overlooking the Hollywood Bowl, a little funicular in downtown Los Angeles called Angels' Flight!

What books like Connelly's are not-- and I think this is true of most genre work-- is intellectually or emotionally challenging. The stories have surprises and suspense, but the outcomes are predictable. This is true also of Trollope and most of the other popular Victorians. The pleasure is in the worlds they create, the ride you go on. I don't think of it so much as escapist, but as viewing other worlds from a comfortable railroad observation car.

But now I'm branching out and trying to pick up some books from the past that I missed.

For example, after many years of avoiding it, I finally read Last Exit to Brooklyn by Hubert Selby, Jr. This book was controversial and popular when it came out in 1964. It is, historically speaking, extremely significant as a major break-through in transgressive writing. It's the one that explicitly described all things violent and ugly and grotesque. Along with William Burroughs' work and maybe Charles Bukowski, Selby set the standard for the real world as the lower depths, and for the cult of brutality that has influenced so much American writing of the second half of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first..

The book is actually several free-standing stories and novellas, and probably the most balanced and touching is the one about Georgette the Queen, a charmer who lives a drugged out, operatic tragedy of a life. Georgette is touchingly romantic as she wastes her love on the worthless Vinnie.

Next comes the famously ugly "Tralala" about the teen whore/robber who makes the world's fastest descent into binge alcoholism and ends up brutally gang raped to death. Has anybody ever topped this in fiction for making everyone see how depraved human beings can be? Lots of imitators, but this one has the strength of its conviction.

Then there is Harry who works for the union and has just about no redeeming social value: he beats his wife; steals from the strike fund (but then so do all the union officials); and rapes a little boy.

Vinnie, Georgette's true love, reappears (I think it's the same Vinnie) in the the final section, a long piece called "Coda." Vinnie and his wife have all of their dialogue AND SHOUTING AND PUNCHING IN CAPS LIKE THIS. This "Coda" is probably the most ambitious section with its group portrait of the projects in Brooklyn (probably Sunset Park near Red Hook), made up of various families and multi-ethnic voices: Italian-American, Jewish-American, African-American-- everyone poor, some hopeless, some striving, some stereotyped.

The book is hard on everyone, probably with more misogyny than racism, but there's plenty of racism too and homophobia as well. Wet shitty diapers play an important part in one section; sex is mostly transactional; at once point an untended baby crawls out on a window ledge and the people hanging out downstairs watch with mild interest the drama of whether it will fall or not.

In the end, I don't think you can evaluate this book in a normal way--what works, what gives pleasure-- it is rather a break-through period piece that insists everything is permitted in literature, and, by the way, human beings suck.

In my effort to cover books I have missed over the years, I also read The Conformist by Alberto Moravia, published in 1950. This is probably best known as a 1970 film directed and written by Bernardo Bertolucci, but I had wanted to read something by Moravia, and this is well worthwhile. The first chapter is gripping and richly foreboding: a lonely little rich boy discovers that he likes to kill animals, and has no idea what to do with his feelings and actions. He begins a precarious relationship with a pedophile defrocked priest, who he apparently kills. This extraordinary beginning struck me as possibly the backstory of a mass murderer, but instead, Marcello grows up to be a Fascist in the early years of the Mussolini regime. He is sent on a mission to set up his former professor for assassination. His real passion, however, is to achieve the life of a totally normal person.

The novel is dated by its possibly unconscious homophobia--maybe I'm being too kind to Moravia when I say that. A sexually predatory Lesbian, married to Marcello's former professor, for example, pursues Marcello's wife, who is in her vaguely bovine placidity, Marcello's greatest success in becoming normal.

Moravia pulls us into Marcello's strange, perverse, claustrophobic world view, and somehow manages to make this part-time Fascist secret agent engaging enough that we eagerly read his whole story.

Joan Didion's highly-praised 1984 Democracy was another book on my list of what I'd missed. She isn't my favorite writer--

I always feel she has contempt for most of us--that she would not, in person, give me the time of day. Yet, paradoxically, she works hard and with brilliant effect to bring us to where she is in her books. It's an odd combination of disdain and determination to communicate.

I have caveats about Democracy, but on balance, I think it is a strong novel. It begins by insisting on what it is not--a family epic-- and it drips with cynicism (realistic enough for its time period, which is the end of the Vietnam war). The protagonist Inez Victor leaves her life in the high altitudes of the American political world, and moves to southeast Asia to work for a refugee agency. It may not be a family epic, but it has echos of altruism in the end and a love story.

Didion does not want it, of course, to be "just" a love story. She uses a circling structure and a meta style with lots of narrator commentary on the events. The narrator, called "Joan Didion," is peripheral to events, but seems to know everything. The story telling is somewhere between clever and brilliant, and if I sound critical of that, it's because it feels a little precious to me, a little too "written."

But the story is worth getting through that. The dialogue in particular is a delight--bracing and funny. There is also a weird and wonderful big murder scene and the incident of a runaway, Inez Victor's daughter, who becomes a bartender in Vietnam just as the the Americans are pulling out. One excellent character is the ironic spin doctor who runs Inez's husband's political campaigns, always faithful, even when he sees clearly how bad things are going. He gets a lot of the best lines.

Passages like the one below are typical of how Didion proceeds in this novel:

As a reader you are ahead of the narrative here.

As a reader you already know that Inez Victor and Jack Lovett left Honolulu together that spring. One reason you know it is because I said so, early on. Had I not said so you would have known it anyway: you would have guessed it, most readers being rather quicker than most narratives, or perhaps you would even have remembered it from the stories that appeared in the newspapers and on television...

She addresses and mildly flatters the reader; she reminds us of the novel's structure; she has something to say about the pace of prose narrative, and she makes up fake news stories. This is all more or less amusing depending on your appreciation of cleverness. Personally, I read the book for Inez's sad mistaken life and her quirky, fascinating family and acquaintances-- and for the love story.

SHORTER REVIEWS (notes by MSW if not otherwise noted)

William Tyndale: The Man Who Gave God an English Voice by David Teems

I read this on Kindle (with which "Tyndale" rhymes). Teems, who turns out to be a Christian musician as well as a biographer, tells the story of William Tyndale's life well. Tyndale translation of the New Testament is the precursor to the King James Bible. Much of the beautiful English in the KJV is the same as Tyndale translations.

To offer the sacred books to ordinary people was, in Tyndale's time, not only new but highly dangerous. Sir Thomas More is the villain in this biography, trying to stop this spreading of the Bible in the vulgar tongue. Tyndale was on the run much of his adult life, which wasn't a long one, but managed to do the famous translation from Greek of the New Testament, plus the Pentateuch, plus more.

He was arrested in one of the Catholic German states and after a year of imprisonment and interrogation (with apparently little or no torture), was condemned for heresy, strangled, and burnt. This form of executions was was considered gentle compared to what was going on in England with its grisly murders first of the "reformers" (the rising Protestants), then of the Catholics (including Tyndale's nemesis Thomas More) under Henry VIII.. There was a brief swing back to killing Protestants under Mary Tudor, then back to hounding Catholics under Elisabeth I. What a grim record for a religion ostensible of love.

One striking part of the story is that Henry VIII was given Tyndale's English Testament, probably, by Anne Boleyn, and Henry was moving toward Protestantism even as his agents were hounding Tyndale in Europe.

The argument between 16th century Catholics and early Protestants was clarified for me. The Catholics saw as the final religious authority the institutional Church itself, with all its history and study. For Protestants, the Word of God as embodied in the Bible, preferably in a translation readable by man, was the final authority.

A Book of American Martyrs by Joyce Carol Oates

In a recent issue of this newsletter, Shelley Ettinger praised A Book of American Martyrs, saying it represented Oates back and better than ever. The novel has great energy and class consciousness (it's very tough on liberals). It is amazingly well imagined, especially the internal life of the fanatic doctor-killing Dunphy, and there is also a lot of excellent writing about boxing (the eldest Dunphy daughter, D.D. " The Hammer of Jesus" Dunphy, becomes a boxer). Oates also does a wonderful job on delineating how ideology carried to extremes damages a lot more people than the assassin and the assassinated. She brings in through the voices of various minor characters many points of view on abortion, and she excels in honest appreciation for the strengths of the poor and oppressed.

The Living and The Hunted by Matthew De La Peña

These two linked young adult novels are narrated by "Shy" Espinoza, a 17 year old Mexican-American who is very likable, full of both self-doubt and reasonable self-confidence. His world is set slightly in a future that is just dystopian enough to feel both realistic and frightening.

I assumed The Living was a self-contained story, but it turns out it leaves things only partly solved, and carries on into The Hunted. I particularly liked the part early in the first book when Shy takes a summer job as a towel boy on a cruise ship heading out into the Pacific. Lots of class insight, and Shy falls in love, gets sort of rejected. There is a mysterious suicide, and then a tsunami and a lifeboat. All of which was plenty of adventure for me, but it's only the beginning.

The survivors end up on an island where it turns out medical research has been underway. The corpses start to pile up-- death by murder, massacre and a terrible illness. The book ends with even fewer survivors--five people including Shy and a mysterious shoeshine guy who is really (I think) special ops.

And then we're off on The Hunted. The little group sails home for California where there have been earthquakes and more of the deadly disease.The second book has moved from mildly dystopian to pretty much post-apocalyptic. More good guys die, along with tons of bad.

Through both books, Shy's voice holds it all together. This second novel ends with a few things still open for a possible third novel. It is inventive and gripping, and I look forward to more of De la Peña's work.

The Book of the Dead Muriel Rukeyser (a new edition with an introduction by

Catherine Venable Moore)

This is a very welcome, West Virginia-focused edition of Muriel Rukeyser's long poem about the Hawk's Nest/Gauley Bridge tunnel and worker silicosis in West Virginia. Nearly ninety years ago, hundreds of workers, while digging a big tunnel for diversion of water for power, contracted silicosis lung disease from drilling through silicon rock with dry drills and no face masks. Great numbers of them died. The dry drills and no face masks were all about speed and profit for Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation and their stockholders. This is said to be the largest corporate-industrial crime in US history.

Since many of the workers were brought in for the job from other states, and since many were also black in a time of segregation, West Virginians themselves tend to have had little acquaintance with the events. Rukeyser was herself an outsider, a poet and a New York Jew.

Thus the introduction by Catherine Venable Moore, a nationally known writer from West Virginia, is extremely valuable. She approaches the events as a sympathetic native and makes the connection to corporate crimes that people in West Virginia and the rest of Appalachia do know-- the Buffalo Creek flood, for example, as well as some natural disasters.

Great thanks to WVU Press for this new edition!

Some Books by Victor Depta

Brother and Sister: A Memoir

The Helen Poems

The Little Henry Poems

The Helen Poems especially are an interesting study in verse of single parenthood, from the breakup of a marriage through the vicissitudes of an intense and loving relationship between father and daughter, to the daughter going off on her own.

The Little Henry poems are more addressed to the grandchild, with verse and some silliness, but also the sadness of a grandparent separated by a continent from the beloved. That's one I really take personally.

Get the books online or from the publisher at www.blairmtp.net

FOLLOW UP

On Latin-American writers: Ingrid Hughes says, "Another must read in Latino lit is Junot Diaz. "

Nathan Leslie on Hillbilly Elegy :

Nathan Leslie says of Hillbilly Elegy, "I wanted to love this book, but overall found it underwhelming. My theory about this book is that it caught fire simply as a result of the Trump election. It was all timing. If it was not for Donald Trump, this book would have gone unnoticed. The prose is not terrible and Vance tells his story efficiently, but many others have done so more effectively--most notably Mary Karr's effervescence Liar's Club. Hillbilly Elegy has a great title and the timing could not have been better, but ....This book really...just tells Vance's story. Keep your expectations to a minimum here."

GEORGE BROSI ON APPALACHIAN BOOKS

George Brosi is one of the deep thinkers on Appalachian literature which he has taught, edited, and sold for many years. He is also a political activist, and always worth reading. Take a look at some of his reviews linked on this webssite, and also see his website. Sample writings include:Brosi on Hillbilly Elegy; Brosi on James Still; Brosi on Ramp Hollow (See our take on this book here).

READ AND LISTEN ONLINE

An updated version of Phyllis Wilson Moore's list of Appalachian related young adult novels! I'm proud to be on this list!

Check out a rediscovered piece by David Weinberger on family word games (truth in advertising: I'm part of this family!)-- Lots of fun. This piece made available thanks to the publication Wordways.

Ingrid Hughes, author of Losing Aaron, has a blog on Psychology Today called "Not the Whole Person." A recent posting about schizophrenia and marijuana was extremely popular.

Check out Hyperallergenic Week-end--an online journal of the arts.

An interesting piece online about physicians as storytellers.

A Reading List from the Sewanee Writer's Conference by Lisa Fay Coutley

An interesting story by John Edgar Wideman

An odd piece on Joyce Carol Oates' tweets.

Poet Lucie Brock-Broido died in March (2018). Here are links to some of her poems, and here is her o

bituary in the New York Times.

Rachid Nachlin's story "See Andrew Run" is available online!

NancyKay Shapiro's excellent blog of reviews and ideas for reading, Reading Up: Books and Me.

ANNOUNCEMENTS, UPCOMING BOOKS, GOOD NEWS, AND MORE.

Marsh Hawk Press's yearly poetry books contest is closing soon!

Darren C. Demaree's poetry manuscript Two Towns Over had been selected by Campbell McGrath as the winner of the Louise Bogan Award from Trio House Press. "Darren is a dangerous dreamer, concocting love poems to his home state, and pastorals to his true love. But there's always something more beneath the surface: sex and violence, villainy, mutilation, uneasy redemption and troubled ecstasy. These poems are pins pressed deep in the disfigured heart of America. They work a dark magic on the reader — they're unsettling in necessary ways." Christopher Michel Learn more at Darren Demaree's website.

New Novel By Bill Luvaas

Bill Luvaas's new novel, Welcome To Saint Angel, is just out with Anaphora Literary Press and available on Amazon and elsewhere. The novel is a dead-serious comedy about development gone mad and a rural community’s—sometimes lethal—battle to stop unscrupulous developers and drought deniers from turning their beloved high-desert home into a suburban nightmare. Iconoclastic inventor Al Sharpe and his zany friends must stand up to powerful adversaries to protect their land from the bulldozers. Part environmental fiction, part social satire, it speaks to the impact of heedless development on the natural environment and on people’s lives. To learn more or order the book or go to the publisher's website .

This Red Land by Arthur Dobrin was just published by Nsemia, a Canadian-Kenyan publisher.

Latest poems by Barbara Crooker on her website.

Check Out These Excellent Anthologies of Appalachian Writing

CURRENT FROM IRENE WEINBERGER BOOKS:

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 197

July 12, 2018

When possible, read this newsletter online in its permanent location.

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

.

Latest Meredith Sue Willis news:

Post up on WVU Press's blog, "Booktimist."

Review of MSW's website at Woven Tale Press Central, the web presence of Woven Tale Press.

Book tour with Their Houses in September! I'll be visiting Huntington, WV, Fairmont, Parkersburg, Shinnston,Morgantown, Clarksburg, and Shepherdstown.

Excellent pre-review of Their Houses from Foreword

Contents of Issue #197 Books for Readers:

Two Books by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Delta Wedding by Eudora Welty

Middlemarch Again

Edwina Pendarvis on Gretel Ehrlich

Follow up to Previous Issues

Reviews and Short Takes

One More on Hillbilly Elegy

Manhattan Beach by Jennifer Egan

The Color of Lies by Donna Meredith

Thug Lovin' by Wahida Clark

The Round House by Louise Erdrich

Fools by Joan Silber

Amy Stewart Mysteries

Ron Chernow's Alexander Hamilton

Things to Read & Hear Online

Announcements and News

Anthologies of Appalachian Writing

Irene Weinberger Books

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 197

If you are reading this newsletter, then you are invited to send me a review of a book you like--or hate! I'll take any kind of book, but have some preference for ones that are not getting a lot of play in the media. That includes older books and overlooked books as well as small press, university press, micromini press and self-published books-- anything you want people to read or know about. You have all the rights to your review, so feel free and even encouraged to post it on Amazon.com or Goodreads or wherever else you'd like.

The books I review myself include ones that are popular and commercially published, although those generally only get short notes from me. I have never tried to keep up with all the terrific books being published, but I do like to read books I've missed. Thus, some of my recent reading includes Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Half of a Yellow Sun and Louise Erdrich's The Round House among others. I also try to make occasional forays beyond my comfort zone, as I did with Wahida Clark's Thug Lovin'. Also, this issue I once again have something to say about Victorian novels (Middlemarch one more time!).

First up this issue is Eddy Pendarvis's review of This Cold Heaven: Seven Seasons in Greenland by Gretel Ehrlich. (There's also a short review by Pendarvis of The Color of Lies by Donna Meredith).

As usual, reviews and comments with no other name attached are by MSW.

A Definitely Unparadisaical Heaven: Edwina Pendarvis Reviews This Cold Heaven: Seven Seasons in Greenland by Gretel Ehrlich

I never would have picked up Gretel Ehrlich’s This Cold Heaven: Seven Seasons in Greenland if I’d come across it in a bookstore. I have no special interest in travel books and very little curiosity about Greenland, a country my college roommates years ago referred to facetiously as “the sleeping giant” in their many rounds of “Risk” (a board game that has players represent different nations and vie for global domination).

Ehrlich’s book showed up in a stack of used books a friend gave me to look through in case I wanted to read any of them. Of the books she sent, This Cold Heaven had the prettiest cover, so I started reading that one. The first few pages didn’t impress me much, as the author seemed to strain after metaphors. Either I grew accustomed to them or she left off a little; but by the second chapter, I was hooked on her striking tale of travels on the coldest and darkest island in the world.

I’m still not sure why I liked the book so much. As I read, I wondered if maybe it just made me glad not to be in Greenland. But that wasn’t the main reason. I learned a whole lot about what life is like in

a world that I came to see as both beautiful and implacable in its resistance to domestication. The Greenland Ehrlich describes seems so imposing and austere in its beauty that it must be the opposite of Eden. It made me think about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and why her monster fixed on the frozen north for his end. But the contrast between the icy surroundings and the warmth of the people who populate Ehrlich’s adventures is central to its appeal. Her story includes Inuits who take her along on hunts and long-distance travels by dogsled; and, in a surprising narrative move, she intersperses her account of seven seasons in Greenland with accounts from the journals of the Danish-Inuit explorer, Knud Rasmussen, who spent seven years journeying in Greenland and across the far north in the early twentieth century. This technique allowed her to enliven her story with the exploits of Rasmussen and his comrades and to compare the lifeways he found with those she found nearly a hundred years’ later. The book is filled with exciting tales of wandering across the ice, falling into bone-chilling water, near-starvation, and the bravery of people willing to risk life and limb to survive there.

Another appeal of the book for me was trying to figure out what drove the author to love Greenland so much that she endured the kind of discomforts she described. She never completely won my trust, but she intrigued me and I definitely admired her boldness. Some “facts” I took with a grain of salt. For example, according to Ehrlich, the Inuit people she met belonged to a group that, wherever they live, from Alaska across Canada and in Greenland speak the same language and have done so for centuries. Knowing how quickly language changes across distances of space and time, I figured she was exaggerating some. A quick search on the Internet confirmed that there are Inuit “languages” not one Inuit language and that understanding of one group by another separated by much distance is not the case. She wasn’t completely off the mark, and whether they’re Inuit languages or Inuit dialects might be debatable; but she was romanticizing. On the other hand, I liked her matter-of-fact—neither prudish nor prurient—accounts of what could’ve been capitalized on: the communal and open attitudes toward sex that were common a century ago among the indigenous people who faced so much danger together.

I guess what finally sums up my affection for her book is that Ehrlich introduced me to an exotic new geography and history, alien to ones I’d been familiar with. Even better, she made me feel the cold and darkness surrounding humans in the northernmost latitudes and, in contrast, the warmth of the human spirit facing up to death and disaster to get the most happiness possible out of a short stint on earth. Those gifts from the author (and from the friend who sent the books she’d finished) are a pretty fair exchange for the few days’ time spent reading a travel saga I happened onto.

Delta Wedding by Eudora Welty

I thought I was going to have trouble finishing this well-known novel because of Welty's casual racism. Part of the problem was that I couldn't separate Welty's own attitudes as she was writing in 1946 from those of the white characters of the novel, which is set in 1920's, on a plantation where the family (attractive and quirky and all those things we love about our white

Southern book characters) depends totally on their "Negroes." The problem is that the Fairchilds still think of the people who work for them as "theirs." The black people become a little more complex as the story goes on, but they aren't given any inner life.

I did keep reading, though, and in the end got caught up in this big snakeball of a novel.

The Fairchilds are all presented as spoiled, charming, wildly attractive, and both imaginative and clannish. Many of them get a point of view, including Ellen the mother, who is not a blood Fairchild. She can't be much over forty but has had ten pregnancies. She reminds me with her delicate and sharp perceptions of the mother in Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse. Another important point-of-view is from Laura, the visiting orphaned girl whose mother was a Fairchild.

The novel is held together nicely by a tight time frame (just over a week) and by the wedding (Dabney's to someone "unsuitable," the plantation overseer from the mountains). Threads that lead us through the complex cast of characters include preparations for the wedding, a missing brooch Ellen wanted to wear for the wedding, her husband Battle and his fury over who his daughter is marrying, but also his inability to stand in the way of it. He loves his children fiercely and is constantly threatening to kill or at least beat them all.

Another piece that comes back repeatedly is an incident when the family is walking on a railroad trestle, and the developmentally disabled cousin gets her foot caught in the track. Heroic George stays with her-- but the train stops just in time. Robbie, who is married to George, sees the whole incident as George choosing family over her, and leaves him. But the novel has the ending of a classical comedy– Robbie comes back to George, there's the wedding. All happy outcomes.

Welty seems indulgent to these people who I found to be generally spoiled brats, but it's a fascinating story anyhow..

For a review when it first came out, see the New York Times comments.

Half of a Yellow Sun and Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

I loved Half of a Yellow Sun and admired but didn't love Americanah. Half of a Yellow Sun is a rich and broad war novel, about middle class Igbo people during the Biafran War period. Educated people who live with servants in lovely homes have to leave their places and struggle for food and share sanitary facilities with lots of others. Babies die of disease and starvation. People of no particular political involvement are assasinated.Two major point-of-view characters are Olanna and Ugwu, the former part of the intellectual elite of a university town and the latter a bright village boy who becomes a houseboy for Olanna and her partner.

There is some less-than-spectacular plotting, especially the foreshadowing of coming events (I usually knew when a major character was going to be endangered or killed, or let live), but that is a minor flaw.

Adichie handles beautifully all the important parts of her novel: how war looks on the ground to civilians as well as conscripted soldiers; small details of everyday life; indigenous methods for changing the course of events (how to make someone love someone else, etc.)

She isn't afraid to include a white British male point-of-view character (Richard, who loves Olanna's twin sister Kainene), or to leave some things unexplained or mysterious. She takes on deeply disturbing moral dilemmas, like the gang rape Ugwu participates in while a conscripted soldier. There is also the mystery of what happened to Olanna's charismatic twin sister.

What do we really know about each other across oceans and ethnic divides? We see images of some spectacular horror-- the bloated starving baby or the little body dead in the surf or the girl fleeing napalm with her clothes ripped off. This novel gives us people, and gives us the Biafran war.

For me, Americanah has a feeling of having been written for an audience, with a deadline, while Yellow Sun seems to have been written for Adichie's personal past, for her parents, for her people.

Don't get me wrong: Americanah amply demonstrates Adichie's gargantuan talent. If is innately interesting for what it says about color, race, all sorts of isms--and hair and beauty parlors! But Yellow Sun is a richer novel.

Middlemarch, One More Time

(Also see Joel Weinberger's review in Issue # 192 and a note by Francine Prose about it.)It is probably still my favorite novel of all time. Again I noted how 19th century literature is far more readable to me

than it was fifty years ago– this is not about me being smarter or more patient, because I'm neither, but rather about having become accustomed to the rhythms of the prose, and also no longer afraid of not getting it.

On the other hand, the mystery is gone– that's the flip side (like when I was really young and fantasized about what a samovar was when I first read Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky). What in the past seemed final and tragic now seems to have much more to do with the constant changes of life and young people suffering and finding their way

The saddest figure, in the end, is Lydgate, who dies young and disappointed (I'd forgotten the summaries at the end of what happened to people). His wife, Rosamund Vincy-Lydgate is in a lot of ways the villain of the piece, but also a wonderful example of a Victorian woman's distorted talents. She acts in totally certainty that her pretty face and perfect manners give her eternal moral high ground– and she is superbly persistent in getting what she wants.

Dorothea seems much younger now, and also terribly impetuous. Yes, it would have been great if she had had more space to develop her talents and passions, but this reading I saw many more of her flaws. She represents, (along with Rosamund) the powerfully negative effects of how middle and upper class British women's lives were distorted by the rules of class and gender: "Marriage," Eliot writes of Dorothea, "which was to bring guidance into worthy and imperative occupation, never freed her from the gentlewoman's oppressive liberty: it had not even filled her leisure with the ruminant joy of unchecked tenderness. Her blooming full-pulsed youth stood there in a moral imprisonment which made itself one with the chill, colorless, narrowed landscape, with the shrunken furniture, the never-read books, and the ghostly stag in a pale fantastic world that seemed to be vanishing from the daylight." (Location: 3,903 in the e-book version).

Bulstrode and Harriet Bulstrode are still wonderful in their little subplot, which I still think is one of the best parts of the book. This time I liked Will Ladislaw so much better than in my early readings. I think I originally bought into the "Italian with white mice" comment on him. I always thought he was too light and curly for Dorothea, but that was mostly my romantic over-estimation of her. True, the perfect match for doing good in the world would have been Dorothea and Lydgate paired up, but that's part of the conscious theme of the book: how marriage can break as well as make people (Fred Vincy's love of Mary Garth and their marriage will certainly make something of him).

I was also struck this time by how funny Eliot is– it's a heavy kind of humor, sometimes laboriously built up, but still much funnier than she gets credit for. Sharp, witty Mrs. Cadwallader and her laid-back clerical husband are entertaining and completely believable. Eliot rather idealizes the Garth family, especially Caleb (who supposedly was based on Eliot's father, as was, in part, Adam Bede of the eponymous novel.)

It's really the story of a community, as the name implies as well as a study of marriage– real, in-process marriages, not happy endings. It's a love story with lots of obstacles, there is a little melodrama, some science.

I get it that 21st centurions find it too heavy, too long, but. oh, it's a pleasure to me to dwell in that place for a while.

FOLLOW UP ON PAST ISSUES:

Carole Rosenthal writes, "I always liked Last Exit to Brooklyn too (See our review of it here) and found it very moving back in the day. I even taught it one year; re: Vinnie as a name--lots of Vinnies and Marys in this book but they are not necessarily the same characters."

SHORTER REVIEWS

Manhattan Beach by Jennifer Egan

I liked Manhattan Beach more than enough to recommend it, and I do. There was a lot of brouhaha about it being an historical novel (set mostly during WWII) after Egan's previous experimental novel in linked stories, A Visit from the Good Squad (that book included one story in the form of a power point presentation, for example) and also had a touch of science fiction.

This one is solidly researched, and I enjoyed the world it creates, even if it feels a little clotted with detail. This novel is more conventional, too, than Goon Squad, in using the standard multiple third person point of view among her three main characters, giving each character a chapter or several chapters before switching off. They begin in a scene together and then separate and finally, with considerable satisfaction for the reader, reconnect. There is also one crucial and skillfully handled chapter in the middle which has multiple points of view among two of the main characters and one character's disabled younger sister. The younger sister's sudden awakening from a kind of existential boredom is really stunning.

It sometimes has, for me, a self-consciousness the mars the illusion. That is, Egan rarely lets you forget for long how skillful and brilliant she is and how much effort went into creating the world. But more often than not, I was totally engrossed: the ship wreck and its aftermath; Anna as a little girl; one really knock-out sexual encounter. I just liked the parts where I got lost in the novel more than the times when I stood back and admired the technique.

For a longer review, see the one in The Atlantic.

The Round House by Louise Erdrich

This is very strong, with a mostly thirteen year old boy first person narrator who is sometimes older, reconstructing his thirteen year old self and occasionally telling us what happens to the other people-- who he marries, who lives and who dies. This does not. however, mar the suspense of what is

going to happen in the summer of the novel. It is also satisfying for having a real political theme-- the failure of the law to prosecute rapes of Native American women. There is a lot about modern tribal life and--probably most fascinating to me-- about people who move in and out between Indian and white worlds. There is a white girl who was adopted into a Chippewa family who is one of a set of white twins. The one raised white turns out to be a monster, and the one raised as an Indian, in spite of being stunted in many ways, is the opposite of her twin.

There is bad behavior and monstrous behavior and half reconstructed tradition and powerful tribal bonds and acceptance of dream meanings and visions and ghosts. Beautifully structured and really excellent.

For more, check out the reviews from The New York Times and The Guardian.

Hillbilly Elegy by J.D. Vance

I finally gave in and read it. It is, in fact, better than I expected, as long as you read it as the memoir of a young person. If Vance had just told his story, it would have been sad and a little uplifting and fascinating in its particularities. But Vance makes what I consider the enormous error of extrapolating from his experience to vast generalities about Appalachians. This is best in its comments on the psychology of a damaged but also well-loved young man who has become a real American success. He is at pains to claim that he is still a hillbilly, even if he shops at Whole Foods and usually controls his impulse to fight physically if his honor seems impugned.

What I actually like best is his portraits of the people around him who did not end up at Yale Law School, who made changes in their lives and have had solid successes of a far less spectacular kind: his grandfather stopped drinking and became an essential support of his family. Vance's aunt ran away to an abusive marriage, but left it and founded a family with a kind man. Vance's sister also got pregnant early, married, and seems to be living the kind of striving and loving life that surrounds us quietly even in the highest crime and drug neighborhoods in the country.

There are, in other words, a lot of ways of having a fulfilling life besides going to Yale Law School and learning the ins and outs of life among the elite. It's a decent story, but just not everything Vance wants it to be.

See Denton Loving's review of the book in this newsletter , and also take a look at my notes on Ramp Hollow, which sets out an interesting theory for how some of the so-called hillbilly folkways came to be.

Edwina Pendarvis on Donna Meredith's The Color of Lies

Donna Meredith's The Color of Lies is about a teacher in a school in Georgia where most of the

teachers (including the novel's protagonist) are white and most of the students are black. The teacher is a widowed mother of two sons and she is the daughter of an alcoholic father (his wife, her mother, is dead).

Meredith manages to raise lots of serious issues and have her vulnerable but quite competent, slightly overweight female lead confront them in very human ways. One of the things I like about the book, is her sort of placing in parallel the daughter's overeating with her father's alcoholism. She doesn't come out and say "think about these two frailties and what they have in common" just as she doesn't get preachy over any of the big issues that are raised in the story. Really relevant to so much that goes on in schools everywhere these days. This book is worth reading for entertainment and for thinking about what's right and wrong in the situations. I hope some teachers pick it up for their professional development book groups!

Thug Lovin' by Wahida Clark

Thug Lovin is what is usually called urban or street lit, but with a romance angle. The author,

Wahida Clark, has herself spent time in prison and is now also a publisher and motivational speaker as well as a writer. This is actually #4 in a series with some of the same characters. The sex is explicit, vulgar, and obvious, and also very hot! But there is equally explicit description of brands of cars, clothes, alcohol, high end drugs, clubs and dancing, and travel.

The main characters are married and starting a family, which interested me, and they aspire to fidelity and love, but there is inevitably with this setting, infidelity.

There are also sudden nodules of violence. Trae, the romantic lead and mostly loving husband, is also a stone cold killer. He murders the man who killed his friend (okay, that has a kind of moral excuse), and he also puts down a probably schizophrenic woman who is in his way.

The marriage begins to fall apart, mostly because no one can ever say no to sex.

What I can't figure out is if this is supposed to show what it calls "thug life" in a way to keep young people out of it, or is it really making thug life attractive? Power, sex, consumer goods, more sex. It is egalitarian in that its women seem to want "dick" as much as men want "pussy." There is a lot of action, but it sounds exhausting to me. Surely these 30 something characters will either get dead or old someday soon.

Fools by Joan Silber

This is a book of short stories very loosely linked. A Florida hotel appears a couple of times; an apparently-shallow Frenchwoman

commits a minor crime, but comes back matured and complex in the final story. There are several young male narrators and an appearance by Dorothy Day of the Catholic Worker in the first story.

The last story had a ending, but the worlds of the stories are thick enough and engaging enough that I wanted novels. I don't know if this is me or the book, that maybe four of the six seemed to have plenty of narrative for a complete book. So maybe I'm just straight up wrong (I always want things I like to last longer), or maybe Silber rejected ideas for novels and turned them, extremely efficiently, into stories.

Anyhow, she's good, can give shape to anything, and cover long periods of time in the long story form with great aplomb.

Girl Waits With Gun and Lady Cop Makes Trouble by Amy Stewart

The first book is better than the second one, which I read first (Lady Cop Causes Trouble). Girl Waits With Gun, seems more serious. There are flashbacks to how the main character Constance had an illegitimate daughter with a Jewish Singer sewing machine lover!), and there's an illegitimate baby in the plot as well, which gives an emotional connection to the crime fighting. The villain is a nasty Captain of Industry who abuses women and uses his goons to threaten and attack the Kopp sisters. Over the course of the book, Constance, who needs and wants a job but is frustrated by the limitations for a woman in 1915, begins to learn what will be her trade– how to sleuth.

Sheriff Heath a good character, as is sister Norma and the supposed little sister Fleurette who is a theatrical teenaged seamstress.

The second book felt lighter and thinner, but the research was fun, New Jersey and New York City in early days of World War I when New Jersey was still mostly bucolic. There is mention of labor struggles in the city of Paterson, and there is an appearance by "Dr. Williams," who I missed entirely was Dr. William Carlos Williams.

Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow

I am not even going to try to do justice to this excellent biography (Lin-Manuel Miranda's source and inspiration for his wildly successful musical play). It is just super, and very, very long: I started reading it

on a library-borrowed Kindle e-book and saw pretty quickly I had no chance of finishing it before the loan ran out, so I bought a cheap used hard copy online.

It's worth reading on many levels, but especially how it shows a time of incredible polarization of politics--yes, probably as ugly as now-- with feuds and scurrilous language and, of course, dueling, which is explained in enough depth that I think I've finally begun to get what it was about.

No wonder we have wars.

And of course, Hamilton's life story truly is amazing. He was brilliant in multiple ways, a fantastic mix of genius and occasional extreme bad judgement. He's the great voice of commerce and capitalism, but he's also personally honest, and a strong abolitionist. His great nemesis, Jefferson, is all about democracy, but of course, simultaneously a deep-dyed hypocrite who freed very few of the enslaved people who served him. Even among his children with Sally Hemings he only freed two formally, supporting the surreptitious disappearance of the two lightest skinned, who apparently passed into the white world.

For more on the Hemingses, see my enthusiastic review of The Hemingses of Monticello.

Talking about contradictions in Hamilton and the other Founders doesn't begin to capture the complexity, but Chernow's book is a tremendously worthwhile read.

THINGS TO READ AND HEAR ONLINE

Francine Prose's Five Classics to Read and Re-read--one is Middlemarch, of course.

Literary Hub has links to 25 Alice Munro stories to read online! Wow.

Latest reviews from George Brosi's Appalachian Mountain Books

Climate Fiction

Just for fun: Title Generator for all genres: Obsidian Warrior and Demon and the Dark!

5 Tips for Writers by Mystery writer Laura Lippman

Two lovely stories about the connection between the elderly and the young as well as about Jewish life in the present day by writer by Lewis Brett Smiler:"The Old Rabbi" and "The Yiddish Burial Ceremony"

ANNOUNCEMENTS AND NEWS

Don't forget to subscribe to the CRWROPPS listserv for submissions opportunities.

Writing prompts and exercises from Poets & Writers.

My writing exercises.

Contests! See The Masters Review list of current contests.

Woven Tale Press's latest Literary and Art Competition.

Fiction Collective contest

Jeff Biggers' latest book is Resistance: Reclaiming an American Tradition, which came out on July 4th "Well-informed and witty...Biggers succeeds in showing how the long tradition of resistance movements

continues today."--Publishers Weekly "A widely ranging history of intellectual and moral resistance within American politics...The author writes clearly and with a firm grasp of historical comparison intimately focused on compelling figures." —Kirkus Reviews Jeff Biggers website

The following poems "Happiness" and "This Summer Day" were added to the "online poems" section of the Barbara Crooker website.

Welcome To Saint Angel by William Luvass has just gone up on Vimeo. In this David versus Goliath story for the 21st Century, small land owners take on greedy developers to save their rural homes. Bill Luvaas's novel is just out with Anaphora Literary Press and available on Amazon and elsewhere. The novel is a dead-serious comedy about development

To learn more or order the book go to the publisher's website .gone mad and a rural community’s—sometimes lethal—battle to stop unscrupulous developers and drought deniers from turning their beloved high-desert home into a suburban nightmare. Iconoclastic inventor Al Sharpe and his zany friends must stand up to powerful adversaries to protect their land from the bulldozers. Part environmental fiction, part social satire, it speaks to the impact of heedless development on the natural environment and on people’s lives.

"In the mildly apocalyptical near future, a community of colorful high desert characters fight off developers and water thieves during CA's worst drought. These decent whackos...transcend their flaws with hilarious courage. SA is a painful, redemptive belly laugh and well worth it." - Doug Peacock, Environmental Activist, Author of Grizzly Years

ANTHOLOGIES OF APPALACHIAN WRITING

IRENE WEINBERGER BOOKS:

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 198

August 23, 2018

When possible, read this newsletter online in its permanent location.

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

Some of this Issue's Reviewers

Donna Meredith Belinda Anderson Phyllis Wilson Moore Eddy Pendarvis Dolly Withrow

Contents Issue #198

Book Recommendations from Dolly Withrow

Earthly Remains by Donna Leon

The Land Breakers by John Ehle

The Leavers by Lisa Ko

Marking Time by Elizabeth Jane Howard

Middlemarch Reviewed by Belinda Anderson

The Mill on the River Floss Reviewed by Eddy Pendarvis

The Reluctant Fundamentalist by Moshin Hamid

Chuck Kinder's The Silver Ghost Reviewed by Donna Meredith

Vada Faith by Barbara Whittington Reviewed by Phyllis Wilson Moore

Wet Work by Donna Meredith Reviewed by Phyllis Wilson Moore

Follow up to Previous Issues

Reviews and Short Takes

Things to Read & Hear Online

Announcements and News

News!

If I'm in your neighborhood this fall, please stop my one of my appearances in the schedule below! I'm in West Virginia in September and then back for the Charleston Book Festival.

Also, for me and all the other authors--if you read one of our books and like it, please consider posting short reviews on on Amazon, Good Reads, and/or Barnes & Noble. These online places have become increasingly important for selling books. I recycle many of the reviews I write for this newsletter at Amazon and the others.

Meredith Sue Willis's appearances, Fall 2018

Monday Sept. 17, 2018: 7:00 PM Writers Can Read, Huntington WV

Tuesday Sept. 18 Fairmont State University, Fairmont, WV 1:30 - 2:45 College Class; 3:00 to 4:15 College Class; 7:00 PM--Reading Folklife Center

Wednesday Sept.19 Parkersburg, WV Wood County Library 7:00 PM

Thursday Sept. 20 Shinnston, WV Library book signing, 1:00 - 4:00 with a short reading at 2:00 PM

Friday Sept. 21 Morgantown, WV Barnes & Noble 6 to 7:15 Reading/discussion/writing workshop

Saturday Sept 22 Clarksburg, WV Library/Waldomere 11:00 am--1:00 PM: Writing workshop: Starting Your Novel! 2-4; Meet and Greet

Sunday Sept. 23 Shepherdstown, WV Four Seasons Bookstore 1:00 PM

October 1: New York City: Novel Writing at NYU's SPS in New York begins

Saturday, October 6th 2:00 to 4:00 Turn of the Corkscrew, Rockville Centre, Long Island–Reading and Workshop

Thursday, October 11 Montclair, New Jersey, Montclair Library, Write Group 6 - 8

Tuesday, October 16 WORDS bookstore in Maplewood, New Jersey 7:30 PM reading

Friday Oct. 26 Charleston, WV Book Festival workshop 10 AM

November 3, 2018 New York City: Jump Start Your Novel One Day workshop at NYU's SPS

Wednesday, November 14, 2018 Next Year's Words: A New Paltz Reading Forum, Jewish Congregation of New Paltz Community Center, 30 North Chestnut St. (on Route 32) from 7:30 PM to 9:30 PM New Paltz, New York.

Thursday, November 29 New York City: Reading at the Jefferson Market Library in New York, NY with Diane Simmons 6:00 - 8:00

I've been pretty busy with all this the last few weeks, and I've done a little reading. Most of my book comments this issue are in the Short Takes section, while the longer reviews come from a number of kind friends. They include essays on the work of George Eliot, Chuck Kinder, Barbara Whittington, and Donna Meredith. The reviewers include Belinda Anderson, Donna Meredith, Phyllis Wilson Moore, Eddy Pendarvis, as well as a special list of favorite books from Dolly Withrow.

Take a look!

MSW

“In death they were not divided,” A Review of The Mill on the Floss by Eddy Pendarvis

Not long ago, I came across an old schoolbook my mother has kept for years, probably not one of her own schoolbooks—the inside cover has a childish cursive naming “Horace Thacker” as the owner. Anyway, I was surprised to find that one of the stories in that fourth-grade reader, published in 1918, is an abridged excerpt from George Eliot’s Mill on the Floss. Entitled, “Maggie and the Gypsies,” the excerpt omits the hardest words, like “obloquy,” and has a short glossary of not quite as hard words, such as “treacle” and “placid.” I’m sure one reason for including the excerpt was to acquaint children with “classic” literature. Other authors represented by stories or

poems in the book were Jonathan Swift, Victor Hugo, Robert Louis Stephenson, Lewis Carroll, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Johannah Spyri (author of Heidi), with, as my list suggest, male authors far outnumbering female authors.

I wondered if another reason to include the Eliot excerpt was because it featured a girl. It was one of just a few stories with girls as lead characters. Most were about girls helping other people, like a story about a lighthouse keeper’s daughter who risked her own life to save survivors of a shipwreck. The Maggie in the excerpt isn’t self-sacrificing, though. She has run away from home to live with the gypsies. The excerpt ends with Maggie’s being glad to be returned to her family, as the gypsies were far less appreciative of her than she’d expected them to be—they definitely weren’t going to make her their queen.

However, Maggie’s character as developed in Eliot’s novel is certainly self-sacrificing. To me, she is one of those unforgettable women in literature, like Sophocles’ Antigone, Thomas Hardy’s Tess, and, yes, Margaret Mitchell’s Scarlet O’Hara. Maggie is a headstrong, self-pitying, ugly duckling of a child who, naturally, grows into a beautiful woman. Her mother, Bessey, is ashamed of Maggie’s behavior; her father, “Mr. Tulliver” (“Mr.” even to his wife), takes up for the “little wench”; her brother, Tom, puts up with her, mostly. Maggie is sometimes resentful toward her mother; she loves her father dearly, and she adores her brother. Conflict between her desire to please her father and brother and her desire to make other choices drives the plot.

In re-reading Mill on the Floss and thinking about that fourth-grade reader, I wondered why read Victorian novels now? Wouldn’t the time be better spent reading something contemporary? I know, supposedly the quality of a work is established if it’s stood the test of time; but there are books of equal quality that have been published in the 21st century. If I looked up other reasons, I’d see a mention of the historical value of classics in helping us to understand, among other things, what’s changed and what hasn’t in the way people think and act. Published in 1860, Mill on the Floss depicts middle-class lifeways in a small town in the middle of England in the 1820s as charming and disturbing.

Part of the charm is the nostalgic perspective of the story. The narrator and characters look lovingly on the past. Eliot’s understanding of the deep identification with nature that is shared by people whose childhood was spent playing outside; her apparent love of myths and fairy tales; and her patronization (in good and bad ways) of children, rustics, and “underlings” are part of her popular appeal.

The “Midlands” dialect Eliot has many of her characters speak is charmingly quaint. Especially notable to me was the use of the word “doubt.” For example, in bemoaning Maggie’s dark hair and skin-coloring, one of her aunts says, “I doubt it’ll stand in her way i’ life to be so brown.” The context makes clear that she means she fears it will stand in Maggie’s way. Another example from an aunt reads, “But I doubt high living and high learning will make it harder for you, young un, nor it was for me.” The speaker means high living and high learning may make life harder for Maggie than it’s been for the aunt, who has the advantage of very little education. In sentences like the latter one, “nor” seems to mean “than.” I liked coming across that substituted “y” ending so typical of English and American dialect, as in “baloney” for “bologna.” Maggie’s mother dreads losing her good “chany” (china) in the family’s financial disaster.

Eliot’s use of dialect, though not as heavy as the dialect in Sir Walter Scott’s novels, is reminiscent of his. Fond of Scott’s novels, Eliot has Philip, the character who is truest in his love for Maggie, turn up with the second volume of Scott’s The Pirate in his pocket one day when he and Maggie are on a walk. Maggie tells him she’s read the first volume, but couldn’t get the second volume, and so doesn’t know what happened to Minna, the novel’s heroine.

This scene and some others make me want Philip to be the narrator of The Mill on the Floss, the one who remembers Maggie as a child. After all, Philip has the ending of one woman’s story in his pocket and, as the last person mentioned in the book, he knows the ending of Maggie’s story. His first name “Philip” has “love” in it from the Greek “philia,” and his last name “Wakem” is easy to link to his efforts to get Maggie to wake up and consider what will make her happy and fulfilled, rather than trying to live the way her brother and father want her to live. In other words, he tries to keep her from being so self-sacrificing. He fails, and the novel ends in romantically satisfying tragedy.

This disturbing isolation of a 19th century woman unable to fit into a society which is in many senses too small for her is repeated in infinite regression in the novel. Maggie’s alienation is foregrounded in the novel, but every character treated in any detail is alienated from other characters in some important way. Even Philip, who seems emotionally closest to Maggie, never fully connects with her. His truth is not her truth. The terrible flood at the end of the novel seems like a deus ex machina to eliminate a problem that has no real solution. When Maggie is finally united with her beloved brother, the book ends. In the alienation of individuals from each other, the story recognizes not only the devastating effects of industry and business on agrarian ways of life, but the possibility that shared understanding of truth also suffers from modern realities, which are divergent, complex, and rife with conflicting material interests. Read in the context of our current political economy—in which truth is not just contested but often irrelevant to outcomes, George Eliot’s classic, The Mill on the Floss, is as prescient as it is historical.

A Middlemarch Meditation by Belinda Anderson

Somehow Middlemarch had escaped me until recently. I had read other works of Mary Ann Evans, writing as George Eliot, but never Middlemarch. When I discovered it was available as an audiobook through my local library, I immediately checked it out. The appeal of listening to a classic read in a charming British accent overcame the somewhat daunting prospect of an unabridged recording of a 800-page 19th-century novel.

Just as I’d hoped, I thoroughly enjoyed Middlemarch, though it does take a bit of commitment at first to shift into the author’s measured pace. But Kate Reading, in her performance for Phoenix Recordings, is brilliantly vivacious. She understands how to enunciate the narration so that the flavor of the writing, from humorous to dramatic, is imparted – too many actors use I’m-reading-you-a-story

voices. Her renditions of the characters’ voices were appealingly distinctive.

I came away with the impression that Middlemarch is a literary soap opera, elevated by the author’s astute observations of human nature. Or: Middlemarch is an examination of human nature, cloaked in a compelling soap opera plot.

There are many lofty summations of Middlemarch that address politics, religion and other themes. This synopsis from the Avid Reader’s Musings blog is perhaps the most succinct: “Everyone has their own secrets and money problems and everyone knows everyone else’s business.” In a later post replying to a reader’s comment about the length of the book (“Holy crap,” to be precise), Melissa, the Avid Reader, said, “Audiobooks are perfect for slow classics. They become so much more accessible when someone is telling me the story.”

As my listening to the book proceeded, I began to better appreciate Eliot’s discussion of her characters in a manner that might at first seem like author intrusion, but becomes more of an invitation to us to consider our own judgmental natures. Just as we’re getting riled on Dorothea’s behalf about the behavior of her husband, Casaubon, the author directly asks us to consider his point of view. Perhaps the warmth of Kate Reading’s voice made me more inclined to accept the author’s discussion points. I found myself reflecting that yes, all of us need to try to better understand others’ points of view.

During the period it took me to listen to the audiobook, Middlemarch kept popping up on my radar. I came across My Life in Middlemarch, a book by Rebecca Mead dedicated to Mead’s experience of the novel. (I read the book in print, but Kate Reading also narrated it for Blackstone Audio.)

Mead explores the book in the context of the life of George Eliot’s life, even describing Eliot’s work routine: “most days, Eliot retreated upstairs immediately after finishing breakfast, at 8:00 a.m., and worked steadily for five hours.” Very admirable. But this is the ultimate writer’s dream: “Affairs were arranged so that she was as free from domestic concerns as possible. Two servants … kept the household running along well-established lines.”

Mead addresses directly my experience of feeling called by Eliot to expand my compassion, in quoting a letter Eliot wrote in 1857: “My artistic bent is directed not at all to the presentation of eminently irreproachable characters, but to the presentation of mixed human beings in such a way as to call forth tolerant judgment, pity and sympathy.” Her intent seems very relevant today.

In an essay written the year before, in 1856, Eliot said, “Art is the nearest thing to life; it is a mode of amplifying experience and extending our contact with our fellow-men beyond the bounds of our personal lot.”

(However, Mead says, she has not been able to verify a very popular quote attributed to Eliot: “It’s never too late to be what you might have been.”)

Mead neatly distills this theme as “we each have our own center of gravity, but must come to discover that others weigh the world differently than we do.”

Eliot’s very last line of Middlemarch, a tribute to Dorothea, echoes her essay’s stated intent about contact beyond the bounds of our personal lot: “But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.” (The original manuscript, according to Mead, concluded with an addition phrase: “having lived a hidden life nobly.”)

With such a striking conclusion, I can understand why author Anna Quindlen called Middlemarch perfection, in Pamela Paul’s By the Book feature for The New York Times Book Review. She ranked it with Bleak House and Pride and Prejudice as contenders for her favorite book of all time.

Author Gary Shteyngart confessed in another of Paul’s interviews to being a new discoverer (like myself). When asked what was the best book he had read recently, he said, “Middlemarch! Can you believe I read the whole thing? When I finished it I expected a Publishers Clearing House-type van to pull up to my house and some British people to pop out and present me with a medal.” When he was asked what books he was embarrassed to not have yet read, he said, “Dickens’s Bleak House. What’s wrong with me? On the other hand, I finished Middlemarch! So lay off me.”

He should check out London Records’ audio recording of Bleak House. It’s read marvelously -- by Sir John Gielgud.

And it’s abridged.

The Silver Ghost by Chuck Kinder Reviewed by Donna Meredith

First issued as a hardback by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich in 1979, Chuck Kinder’s The Silver Ghost is now available as a paperback published by Braddock Avenue Books.

While the novel’s characters are not always likeable, the story captures the essence of a mythical era in American history, the late 1950s. Kinder’s great accomplishment in The Silver Ghost is a nearly perfect rendition of teenage angst. In the first half of the book, anyone can relate to Jimbo Stark. His mooning over his girlfriend Judy. The impossibility of meeting the macho expectations of his war-obsessed father. The agony when Jimbo is forced to move away from friends and girlfriend to finish out his senior year in a podunk town in southern West

Virginia. He is the epitome of the disgruntled, rebellious teenager, the only poet in a small town high school, wallowing in despair as he imagines his girl cuddled up to some other guy at the Valentine’s dance.

Kinder’s over-the-top, poetic language captures the intensity of a lovesick teen: “It is the late 1950s and America is a lush, electric, song-filled garden for teenage truelove, and Jimbo and Judy fully expect that their own truelove will grow and grow until the end of time, until the twelfth of never.” Reality is fluid in this story, dream-like, shifting from real events to movie scenes, both incorporating fragments of songs, all while diving through time.

Jimbo’s adulation of a popular movie star rings true. He attempts to emulate James Dean’s iconic cool in Rebel Without a Cause, a point Kinder emphasizes through lyrical variations of this image: Jimbo “arched his eyebrows and wrinkled his forehead and let his lower face collapse into smiles, which was his perfectly Cool James Dean moviemask, mastered after earnest effort.” The protagonist is even called Jimbo after James Dean’s role in Rebel.

The Silver Ghost of the novel’s title is a Porsche belonging to Judy’s brother Frank. A status symbol, it could burn every other car in town. Quite generously, Frank lets Jimbo borrow it for dates.

When Judy spots a diamond ring with a heart of perfect small pearls shaped around it, she declares it is “the only ring in the whole wide world for us.” Lovesick Jimbo is determined to buy this token for his girl. He sells all his own treasures, but still doesn’t have enough money. Desperate, he steals the soldiers in his father’s painstakingly assembled WWII battle scenes, scenes representing the defining moments in his father’s life. The theft delivers a devastating gut-punch, psychological revenge against the father who never understood his poetry-inclined son, replicating the father/son relationship in the movie.

Banished from his more-than-irate father’s sight, Jimbo suffers through his senior year angry, alone, and lonely. He finds relief by drinking alcohol, smoking and telephoning Judy.

After an epic struggle to return home and deliver a Valentine to his beloved Judy, Jimbo learns from Pace, his best friend, that “teenage truelove” isn’t so true after all. There’s a snake in the “song-filled garden.” Judy has slept with Jimbo’s rival, a star football player.

Devastated, Jimbo steals the Silver Ghost and the two boys set out for Florida. Unfortunately, the gullible teens meet Morris, a charming criminal who preys on young boys. Jimbo soon finds himself on a bad road, one filled with robberies, violence, and betrayals.

In the novel’s final scene, the adult Jimbo sits alone in a bar. He wonders if it wouldn’t have been best if he’d committed suicide back when the authorities caught up to him—died at the moment he was “perfectly seventeen,” with his youth preserved forever like James Dean, who died in his Porsche at the age of twenty-four.

Kinder’s structure allows events to flow freely through time, with a prologue and epilogue adding thematic development and perspective. Fishing imagery appears frequently in this literary novel, with meanings that shift and waver as if seen through water. Sometimes the image seems to suggest fear of delving too deeply into the past: “You never, however, try to imagine fishing that 180 degrees of current lost in space and time.” Kinder himself never flinches from an author’s duty to dive into the past and surface with characters fully formed and seriously flawed.

The novel’s first draft was completed in 1977 while Kinder was an Edith Merrilees Fellow at Stanford. In a December 2017 interview, Kinder said he has always seen the world through a cinematic lens. He claims almost every word of The Silver Ghost is true, close to autobiography, except for a homosexual rape scene late in the story.

Born and raised in West Virginia, Kinder taught at the University of Pittsburgh for more than three decades and served as director of the creative writing program. His other books include Snakehunter and Last Mountain Dancer, recently re-published by West Virginia University Press; and Honeymooners, as well as several volumes of poetry.

Vada Faith: A Novel by Barbara Whittington Reviewed by Phyllis Wilson Moore.

Set in the fictional small town of Shady Creek, West Virginia, the novel Vada Faith has a very southern feel to it. Vada Faith Waddell and her twin sister Joy Ruth are co-owners of the only beauty shop in town. Their lives are tangled in every way possible including their mutual attraction to Vada Faith's husband, John Waddell.

Back in high school, the handsome young athlete was Joy Ruth's boyfriend. To be blunt,Vada stole him. Sister is still single while Vada Faith and John live happily in their old historic house with their twin daughters. Life is good.

Unbeknown to everyone, Vada Faith has issues. She wants to be someone. She wants to help someone. As far as she is concerned, she has never done anything significant and she never will. She never has enough money to spend. She wants a big new house. Now.

When a local couple places an ad offering a huge payoff to a qualified surrogate mother, she answers it. The wealthy couple is prepared to be very generous with the surrogate fee and will absorb all expenses. In addition, they offer perks: clothes, jewelry, etc. If she agrees, she will be the first surrogate mother in the county, ever, and she can quit waiting for the big fancy home. How can she refuse this childless couple?

The way Vada Faith sees it, it should be her decision, and hers alone. In fact, she keeps this good deed a secret from everyone (except her sister) including John and her daughters. After all, it is her body and she is a mature woman, right? Duh.

Pregnancy as a secret is laughable and so is this humorous novel. Her family's reaction and that of the townspeople are just what a thinking person might expect, ramped up a tad.

The novel covers a serious subject but is chock-full of southern humor in a style reminiscent of Fannie Flagg. I can see a young Dolly Parton as Vada Faith and can hear the gossip-fest in the shop.

Water, Water, Every Where and…. WET WORK by Donna Meredith Reviewed by Phyllis Wilson Moore

Authors strive for a hook, and this novel certainly has one. In four succinct pages, Donna Meredith, introduces a likeable illegal immigrant, a former Mexican engineer named Paulo.

Paulo, soon to return to his beloved family in Mexico, is eager to rejoin his mother and wife and see his newborn son for the first time.

In just a few paragraphs, I like the homesick Paulo. Then, bam, Meredith shoots him dead. On the fourth page. Now I call that a hook.

The novel is an environmental thriller set in Florida, first in a swamp, then a university campus, and then out into the lush rivers and byways. I’m rather new to the environmental novel but I like thrillers, especially when they are set in places I’d like to visit, and I like novels with characters from other cultures.

The novel has interesting characters and Summer Cassidy is a good example. Pretty, intelligent, and quick with a witty response, she is finishing her research for a master’s in hydrogeology. Her work is groundbreaking. Some of the ogres of big business are sure her report will be detrimental to their businesses. As Important donors to the university, they assume a woman as intelligent as Cassidy, a woman in need of a scholarship to pursue her Phd, can be convinced to give more thought to her research findings. After all, just how important is clean water compared to jobs?

Well researched and well written, I suggest readers add this work to their stack of books waiting to be read. I’ll go even further and suggest it be placed on the top of the stack and next to a box of tissues and a tall glass of water.

(Wild Women Writers. Tallahassee, Florida, 2014 )

SHORTER REVIEWS

The Land Breakers by John Ehle

I met the late John Ehle at a conference some years back, and he was handsome and courtly and fragile with age. He was carefully watched over by his wife, the British actor Rosemary Harris. Their daughter is Jennifer Ehle, an accomplished actor like her mother, famous for playing Elizabeth Bennet opposite Colin Firth in the BBC's Pride and Prejudice series. As this opening paragraph indicates, I knew much more about Ehle's wife and daughter than about him, and more's the pity, because his work has is rich and full of adventure.

This novel, and the ones I have not read yet that follow it, concern the European-American settlers of the Appalachian mountains. It celebrates the kind of work people used to have to do for food and shelter: clearing forest, skinning animals, smoking meat; weaving linsey-woolsey. There are natural dangers all around-- the bears are particularly present, and there is a scene with rattlesnakes that I

wish I could forget. Like Harriet Arnow's great Hunter's Horn, this novel doesn't focus on the solitude of hunters and trappers, but rather about people who want a community. They don't all define community in the same way, but they want to be near other people. The main character, although he is only one of many , Mooney Wright, and his long time love buy land on a mountain in what is now Western North Carolina. Shortly after they build their cabin, other people start coming to the same area, and Mooney's beloved sickens and dies.

Soon there are five or six families, all with their own interesting stories, and each representing a type of "landbreaker:" Mooney is physically powerful, adept with his hands, and hard working. An orphan boy, he is about as self-made as is realistically possible. The second group in is led by a patriarch called Harrison who is old and viciously determined to be the big man in his new settlement. He comes with enslaved people, a beaten down son, a new child bride (who happens to be his blood niece), and his daughter and her young sons.

The daughter, Lorry was abandoned by her husband, and is in her own way as determined as her father to find what she needs in this place. She, like Mooney, is especially good at the tasks needed to make a home here. There is also a ne'er do-well musician with a string of daughters. One of them, Mina, is beautiful and imaginative and free-spirited and determined not to be like her mother. Another group lives across the river, primarily made up of hunters.

The big plot question is whether Mooney will pair off with teen-age Mina or turn to Lorry with her knowledge and her sons? The next big question is will the community survive? What if Lorry's original husband shows up and challenges Mooney? Will the wild animals kill all the stock?

There are hunts and conflicts, a murder, that snake story, and a livestock drive that seems to be the settlement's last chance to survive. The book is a wonderful trip, and the answers to the questions the story raises are the least of itspleasures.

The Leavers by Lisa Ko

This is the story of a damaged kid named Deming, sometimes Danie