NYU Novel Writing Workshop

Fall 2023 WRIT1-CE9357 OnlineNOVEL WRITING

WRIT1-CE9357 Novel Writing (Fall 2023)

9-13/2023 - 11/15/2023

10 Wednesdays 6:30 p.m. to 8:50 p.m.

Synchronous online by Zoom

Instructor: Meredith Sue Willis (She, her, etc.)

E-mail: meredithsuewillis@gmail.comUpdated 11-28-23

Class is over--Thank you for being a part of it!

Here are a few more things to read.

This page will stay up till Feb. 1, 2024.

From Victoria Trailes in the chat on 11-15-23:

"Epistolary elements in novels can be very powerful. I took a whole class in college just about the letter writing. The book Where'd You Go Bernadette is a modern epistolary novel (coincidentally also about a mother/daughter dynamic)."

FYI:

MSW does a few manuscript consultations

and occasional private classes.

CURRENT CLASS

Presentation/Critique Schedule

Assignments Due

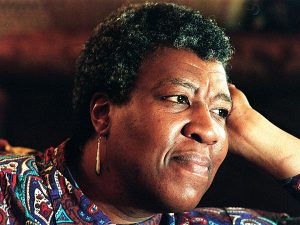

Do you know these novelists? Living and dead, best sellers and not, but all with vibrant, living work. See below for names.

Please note that this site changes often during the semester. It will be updated at least once a week, so check back often.

For an overview of weekly topics, click here.

Current Week "Script" is posted by Noon of Class Day

Optional Text for this Course: Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel by Meredith Sue Willis. This text is not required. (Available NYU Bookstore, from the publisher, and from all the usual online suspects including Bookshop.org.)

OUTLINE OF WEEKLY TOPICS (Subject to change)

Week 1. 9-13-23 Lots of basic Business. Introduction. Essential Importance of the Senses for writer and reader. Places, People.

Week 2. 9-20 Point of View. Presentation of Student Work for Critique

Week 3. 9-27Dialogue and Scene I: Writing Vivid Dialogue; Dramatize versus Summarize. Presentation of Student Work for Critique

Week 4. 10-4Dialogue and Scene II: Scene & Dialogue II: Group Scenes; Dramatize versus Summarize; Monologue (inner speech). Presentation of Student Work for Critique

Week 5. 10-11Structure I: Big Bins. Presentation of Student Work for Critique

Week 6. 10-18Structure II: When, How, & If to Outline. Presentation of Student Work for Critique

Week 7. 10-25Arc of Character and a Short Presentation on What To Do Once Your Novel is Finished. Student Work for Critique

Week 8. 11-1Things Novels Do Better than Movies and Things Novelists Can Learn from Film.Presentation of Student Work for CritiqueWeek 9. 11-8 Revision I: Diction and Fine Tuning. Presentation of Student Work for Critique

Week 10. 11-15 Revision II: Revising Novels. (Final Session) Presentation of Student Work for Critique

A Few Optional Things to Read: (Some may reappear as homework reading).

About Character Arc by Susan DeFreitas on Jane Friedman's Electric Speed

Writing ideas from Kurt Vonnegut by Suzanne McConnell.

Why a manuscript gets rejected--emphasis on the query letter and opening pages.

A good basic piece on setting fiction in the past (genre of historical fiction but also more) by Garth Petterson.

Do you need ideas for starting your novel? Check out MSW's article online from The Writer: "How to Get a Novel Started."

A close reading of a well-made first paragraph (Emily Temple on True Grit)

Deep Point of View (from Masterclass.com

More optional readings

Meredith Sue Willis's grandmother stories available online:

Session 1

9-13-23Business & Introduction of How to Talk about Novels;

Structure of the Class, Importance of Concrete Language

Reading Assignments Due 9-13-23:.

In Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel, read "Strategy 1: Separate Process and Product" or this excerpt from the book :Click on the "Read an Excerpt" at this link link. (Optional)Getting the right spacing between paragraphs in Word

A piece from The Guardian on adverbs

Look over copy editor's marks for times when you want to do hand written mark-ups--or understand the ones MSW puts on your pages!.

Writing Assignment Due 2-23-22:

The first page--a sample of your writing--from your novel! If you haven't written it yet, then it's an important exercise to try.

Business

A lot of business today--apologies to those who have taken this course before.

NYU Rules 'n Regs Here

This class welcomes beginning novelists as well as writers who are well-underway on a novel and need further discussion and stimulation to continue or restart. We will cover a lot of basics fast, beginning with a survey of common terms for discussing novels and a look at novel structure in general. If you feel you need more of the basic terminology and ideas, please take a look at the teacher's book, Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel.

For those with longer or revised manuscripts, this course may be repeated.

This syllabus will be updated regularly online, so please check this web page at least once a week. Access to the website is also available from MSW's home page. Look at the top left.

All writing and presentation selections should be from the novel you're working on.

During the course, you may bring a total of up-to 50 manuscript pages for critique (some of these pages will be for the whole group, some only for the teacher). Assignments are optional and go only to MSW. Anything you turn in to MSW, however, counts towards the total of 50 pages to be reviewed during the semester.

Please be prepared to discuss the work of classmates when they present.

Presentation pieces go to the instructor and whole class. Homework assignments go only to the instructor.

You will receive a grade for this course unless you request a NonEvaluative mark. For the Non-Evaluative, please see the attached form. A copy of this request must be filed with the department. Send it by e-mail to .

No letter grade will be given below a B. To earn a B, you must attend regularly, complete 50 pages to the professor's satisfaction plus present work for critiquing by the class at least once. To earn an A, you must attend regularly, complete the 50 pages, present work for critiquing by the class at least twice, show evidence of having done any outside reading, plus participate in class discussions.

It should be noted that all NYU policies on academic integrity, i.e., plagiarism, are fully in effect in this course. For various NYU policies, click here.

Disclaimer: Syllabus is subject to change due to current events, guest speaker schedule changes, and/or level and interests of students.

No-evaluative Grade Information: if you don't want a grade, you must follow these instructions.

Take a look at weekly topics.

Sign up for class critiques

Pick a session to present 5-10 pages to the class. Everyone should read the material BEFORE class (it will not be read aloud), and the presenter needs to e-mail .doc files to everyone by Sunday night of the class you are presenting on.

Structure of the course & more business. Things we'll do during class-time:

Preferred e-mail-- I'll be charing list unless I hear otherwise.

Send MSW by chat or e-mail: your snail mail address;

Names you want to be called; corrections to e-mail, etc

Readings for homework (some optional, most online)

All writing from the novel you're working on.

Read class members passages for presentation/critique

Mini-lectures (MSW talks)

Discussion (as much as possible)

In-class writing

For general topics by week, click here.

Material you send in for responses ("Homework"). There are three kinds:

1. The weekly assignments should be @ 2-3 pages long. They are not required, but are a good way to move your novel forward. These pages are sent only to MSW. They are due on the day of class (thus, the "Writing Assignments due" for Session 2 are due any time March 2, 2022 (before or after class). If they don't arrive that day, there is no guarantee they will be returned by the next session. You may send longer passages, but please let MSW know your plan so she doesn't get swamped at the end!

2. Substitutions: especially for people taking this class again, or who have an in-process novel--you may send any pages you want to the instructor for feedback. These pages are sent only to MSW. They are due on the day of class (thus, substitute pages for Session 2 are due some time on March 3, 2021. If they don't arrive that day, there is no guarantee they will be returned by the next session.

3. Presentation pieces for critiquing (as short as you'd like, but no more than 10 pp. double spaced, 1 inch margins, roughly comparable to 12 pt. New Times Roman Type face) are sent to the entire class. These presentation pieces are to to arrive in people's e-mail in boxes by Sunday night before the presentation.

VIP: the total pages you may turn in to MSW cannot be more than 50 pp. This includes worked to be critiqued by the whole class and assignments sent only to MSW.

When there is work to critique, be prepared to discuss it by the time the class member presents

III. Class guidelines with Zoom

-- Please have your camera turned on.

-- Put yourself on mute when you're not talking so we don't have to hear your puppy, your partner in the kitchen, etc. The mute button is at lower left of the Zoom screen.

-- Raise your physical hand if you want to speak.

-- Speak one at a time--in practice, this means waiting for the instructor to call on you.

-- Try to be succinct.

-- Listen and respect each other's ideas. We are writing different kinds of novels, and if possible, try to make suggestions based on helping each other write the best novel of the type we are writing.

-- Use the chat function for procedural notes to the instructor ( you got a text from a classmate who can't get in; the name of a book you couldn't think of and wanted to share....)

-- Apologies in advance: I may have to interrupt/cut you off. We try for equal time for each person, and I also have an ambitious plan for what to cover.

-- Technical note for Mac Users on Zoom: To view screen share in Zoom at full screen, see the top drop down menu and set to "100%"

IV. Go round of introductions-- name, a line or two of background (try not to apologize that you have not written much yet!)

V. WRITE

Using Timed Writing, write a physical description (not narrated but rather focusing on what can be observed with the senses--especially those other than sight) of a character the protagonist meets for the first time.

In Timed writing, you write steadily for given time. Write slowly but steadily. If you get stuck, repeat a word till you're unstuck. But try to keep the words coming.

VI. Share

VII. Senses in writing

Extremely Mini-Lecture on the uses of description

First: Concrete description is best, using the senses whenever possible. Like the Courbet apples above, we best communicate in words what we see in our minds by sharing the lowest common denominator: red, warm, smooth, crisp, sweet, juicy. That is to say, sense details. It's not the only thing in writing, but it is essential for those of us writers (novelists and other fiction writers!) who aren't illustrating their work or depending on costume designers and actors to give the timbre of the voice, the fabric and folds of the cloak.

Second: Drafting lots of rich description will help you see your work more completely and clearly and may even give you ideas for new scenes, new characters, new depth! Over-write as you make your first draft.

Third: In your final product, cut most of the description you drafted. Make your descriptions as concise as possible, retaining only the very best details, See "The Lady Sheriff."

We do Macro (big pictrure stuff) and Micro which means here detail, especially concrete detail.

1. Everything is built with concrete observation and sense details.

2. All senses (not just sight) come into play.

3. Here's an example from fiction-- a story called "Consultation" by Ariel Dorfman

What sense or senses are missing?

4. Here's one I like that describes a person.

5. Example from one of the first pages turned in today.

Separating Process and Product. (Click on "Read an Excerpt." If you have the book, you can read the full version In Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel, "Strategy 1: Separate Process and Product.")

A few important terms Terms for Novel Writing.pdf and Types of novels.

Optional:

Two chapters in Ten Strategies: "Strategy 1: Separate Process and uct" and "Strategy 2: Taste It, Touch It Smell It..."

Advice for Writers from Novelists

Jordan Kisner in The Atlantic on failing to cross cultural divides in fiction (a review of Geraldine Brooks's Horse).

Something to think about: Using the latest technology in your novel

How a story was submitted forty times over ten years, and finally....

VIII. BREAK

IX. Share some.

X. How do we talk about ("critique") novels

What do you find useful? Not useful?

For me, it's always How to make this novel (scene, passage) the best it can be at what it wants to be.

Here's a sheet to help people critique your passage. You might want to print out--use as a reference.

XI. Common Vocabulary

Common vocabulary--Process versus product, pacing, when to dramatize, when to elide. Essential importance of Point of View in all fiction. Scene and summary. What is Scene? Why is it important? The building block of novels. But at the heart is concrete details.Process versus product, pacing, when to dramatize, when to elide.

See Terms we'll be using this semester.

XII. SCHEDULE PRESENTATIONS FOR CRITIQUE.

This is for many people the most important thing. PLEASE GET WORK TO WHOLE CLASS BY SUNDAY NIGHT. Also, part of your job is to read and respond. Ask questions to direct us in what you need. (close line editing? Or is this rough and you mostly want general reactions?

Consider using the critiquing sheet mentioned above (or your own variation on it) for responses.

XIII. Write a Macro Exercise

Macro exercise about the novel you are planning/engaged in. Your novel--write about it, talk about it.

Answer these questions about your novel using this list of Types of Novels if you need it.

XIV. Homework and readings for next week

Writing assignment:

An important room or other place in your novel (indoors or out).

Focus on concrete language and senses, and try to make it psychologically accurate--that is, not every possible detail, but maybe an over view first, or maybe a person entering the space, noticing first the temperature, then one large object, etc.

WHo is tellig this? A first person narrator? The main character from 20 years in the future?

Reading Assignments:

Ten Strategies, "Strategy 4: Find Where You Stand as You Tell Your Story." (optional)

Point of view chart online plus skim a few of these examples of various points of view.

Also, if you haven't read it before, check out the Kilted Warrior example of amateurish (IMHO) omniscient POV.

Session 2

9-20-23

Point of View: Where I Stand as I Tell the Story

Assignments due today:

Writing assignment:

Your main character comes into a room or other place for the first time, indoors or out. Use all or most of the senses to have the character become aware of the place. Focus on the concrete, and try to make it psychologically accurate--that is, not every possible detail, but maybe an over view first, maybe noticing first the temperature, then the sound level, the layout, one particular person...

Also, be aware of who is telling this: is it a first person narrator? Is it the main character from 20 years in the future? It is a godlike omniscient narrator?

Reading Assignments:

Make sure you've at least skimmed the first pages to learn something about the other class members.

A little more on the senses: don't forget we have five (at least) senses. Don't get stuck on sight. Here's an example from fiction-- a story called "Consultation" by Ariel Dorfman. What sense or senses are missing? Why?

Here are several descriptions I like from James Joyce's The Dead: Everything is built with concrete observation and sense details.

Point of view chart online plus skim a few of these examples of various points of view.

The Kilted Warrior-- example of amateurish (IMHO) omniscient POV.

BELOW HERE, INTERESTING BUT OPTIONAL

- Challenge: Revising 3rd Person to 1st Person POV by George Lies

- Free Indirect Discourse: Two (or Three) Points of View at Once? by Eddy Pendarvis

- Ten Strategies, "Strategy 4: Find Where You Stand as You Tell Your Story." (optional)

I. Business

New:

Double space your homework and presentation pieces (for readability)

Please give everything page numbers.

SIGN UP TO PRESENT! I hope for two presentations for each ot you, at least those who want them. Do try for at least one--it's good for you and your novel!

A few things people would like covered: Show & tell; dialogue writing; structure (including movement/pacing & "clearing a path); more complex characters; too many characters; accountability (deadlines); getting out of a slump; improving one's style.

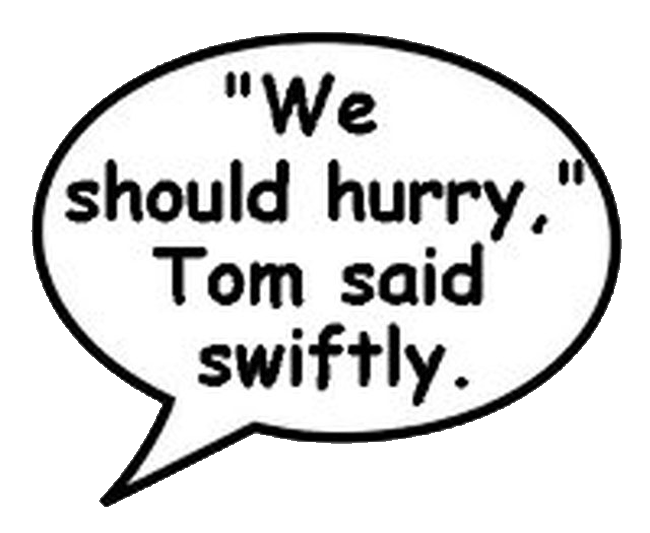

Basic dialog punctuation. Here's a sample of conventionally punctuated dialogue from a story called The Two Lindas. Note where commas come, how "said" is generally the default "tag." Also notice verbs used in preference to participles "(I can't believe it.” She extended her arms and embraced me... " rather than, "I can't believe it," she said, extending her arms and embracing me...." Some languages use dashes; you also see single quotes where U.S. convention is double quotes. There'll be a lot more on dialog later.

Reminders/Old:

Remind about non-eval. Who wants? Who wants no grade? You will receive a grade for this course unless you request a NonEvaluative mark. For the Non-Evaluative, please see the attached form. A copy of this request must be filed with the department. Send it by e-mail to .

Please send Snail mail addresses to MSW.

It's your choice to do the assignments or substitute, but everything should be from your novel. The total number of pages you may turn in for response from the instructor is 50 (that includes pieces presented to the whole group and homework for the instructor alone).

1. The weekly assignments should be @ 2-3 pages long. They are not required, but are a good way to move your novel forward. These pages are sent only to MSW. They are due on the day of class.

2. Substitutions: you may always substitute pages from you novel of your choice.

3. Presentation pieces for critiquing are to to arrive in people's e-mail in boxes by Sunday night before the presentation at the very latest.

II. HOW WE TALK ABOUT NOVELS AND NOTES FOR CRITIQUING

Common vocabulary--Process versus product, pacing, when to dramatize, when to elide. Essential importance of Point of View in all fiction. Scene and summary. What is Scene? Why is it important? The building block of novels. But at the heart is concrete details.

Terms for Novel Writing.pdf and Types of novels.

Who has been critiqued (in class, by peers, by teachers, by editors?) What do you find most useful? Not useful? For me, it's always How to make this novel (scene, passage) the best it can be at what it wants to be.

Again, when you give class members copies of the pages you want critiqued, include questions!

A Short Go-Round... on how you responded to the presenters' writing.

Your responsibilities as a critiquer:

Bare minimum: read and be prepared to talk.

For this class: at least a short paragraph of holistic response and/or answers to the writer's questions.

Even better: notes in the text (what I do: try to catch typos; look for things that can be cut--tighten; things that could be clarified; point out phrases and parts I like)

Objective is to help a writer write the best novel possible of the type they are writing.

III. PRESENTER ONE: (A lot of the "instruction" in this class comes as we go over people's work.)Beatriz Fontes

IV. FIRST PAGES--what POV?

This leads to...

V. A Mini-Lecture on POINT OF VIEW

Essential importance of Point of View in all fiction. The guide through the novel or other. Voice we are listenng to.

But also, for the writer. How we approach and discover our story.

Point of View chart to establish the vocabulary.

Point of view samples

An article on various 3rd persons

illusion of how the story is told

A Point of view problem example: "The Thriller Bar Scene."

Danny Williams on Writing in the First Person" In my own fiction writing—rarely more than a few hundred or a couple thousand words, I'll admit—writing in first person is in one small sense mechanically easy. There's no consideration of what other characters know or don't know or what they may be thinking, so the writer doesn't need to decide how much of that to include, and where and how.

"In first-person narrative, the writer's task is constructing the narrator's personality through the character's use of language. Here's the hard part. The reader will be trapped in an elevator with this person for the duration. If we don't on some level enjoy the way this person talks, we will start looking around for an escape, and likely find that the only way out is to put down the book for "later." And we need to find out who this person is, but this needs to happen gently, piece by piece. If the narrator begins reciting an Apologia Pro Vita Sua, we'll soon be eyeing the little access hatch on the elevator's ceiling."

-- Danny Williams

VIII. BREAK

IX. Presenter Two:

Kristen Ballard

X WRITE

A short scene in which two people in your novel are having a conversation at cross-purposes. This can be something subtle like one wants the relationship to move to the next step and the other doesn't, even though they both are attracted to each other. It can also be totally open: one person is challenging the other to a knife fight. It can be a a business negotiation or a parent and child at the table struggling over the child eating a certain food.

XI. SHARE?

XII. Assignments for next week:

Writing Assignment:

Use the in-class writing: a dialogue in which two characters in your novel are at cross purposes. This can be something subtle like one wants the relationship to move to the next step and the other doesn't, even though they both are attracted to each other. It can also be totally open: one person is challenging the other to a knife fight. It can be a a business negotiation or a parent and child at the table struggling over the child eating a certain food.

Try to have this be from somewhere in the middle or the novel

Reading/Listening Assignments:

Student presentations coming by e-mail attachments.

Short readings on dialogue and scene: : Dialogue Tags ; Types of Discourse; and " Dialogue: The Spine of Fiction." (article by MSW about dialogue online).

A good example of a scene focused on dialogue: note that this one does NOT use conventional dialog punctuation!

Read possibly the greatest summary in twentieth century literature--told not shown!--from Virginia Woolf's To The Lighthouse, the

death of Mrs. Ramsay. The bracketed "scene" is as Woolf wrote it.Ten Strategies, "Strategy 5: Master Dialogue and Scene" (optional)

An eleven minute recorded mini-lecture by me on Scene (optional)

Of possible interest (optional). Chat GPT and writers: research by George Lies:

Wired article on using Chat GPT to improve your writing

Training Chat GPT to imitate your voice/style: from Forte labs

Session 3

Scene & Dialogue

Writing Vivid Dialogue;

Dramatize versus Summarize

Movie version of Great Expectations; a scene from one of

Trollope's Phineas Finn political novels; from the movie version of

Hemingway's story "The Killers."

Presentation/Critique Schedule

For an overview of weekly topics, click here.

ASSIGNMENTS DUE:

Writing Assignment:

Use the in-class writing: a dialogue in which two characters in your novel are at cross purposes. This can be something subtle like one wants the relationship to move to the next step and the other doesn't, even though they both are attracted to each other. It can also be totally open: one person is challenging the other to a knife fight. It can be a a business negotiation or a parent and child at the table struggling over the child eating a certain food.

Try to have this be from somewhere in the middle or the novel

Reading/Listening Assignments:

Student presentations coming by e-mail attachments.

Short readings on dialogue and scene: : Dialogue Tags ; Types of Discourse; and " Dialogue: The Spine of Fiction." (article by MSW about dialogue online).

A good example of a scene focused on dialogue: note that this one does NOT use conventional dialog punctuation!

Read possibly the greatest summary in twentieth century literature--told not shown!--from Virginia Woolf's To The Lighthouse, the

death of Mrs. Ramsay. The bracketed "scene" is as Woolf wrote it.Ten Strategies, "Strategy 5: Master Dialogue and Scene" (optional)

An eleven minute recorded mini-lecture by me on Scene (optional)

Avoid Creative Dialogue Tag Syndrome.

Of possible interest (optional). Chat GPT and writers: research by George Lies:

Wired article on using Chat GPT to improve your writing

Training Chat GPT to imitate your voice/style: from Forte labs

I. Business

Make sure you have Jackie's email: jackiedorward@gmail.com

Here is corrected (I hope!) email list:

philipai@verizon.net,labestseller@optimum.net,

kristennballard@gmail.com,mcc1@nyu.edu,

jackiedorward@gmail.com,

beatrizcosta.fontes@gmail.com,alexisgogh@gmail.com,

birgitmatzerath@gmail.com,1980pom@gmail.com,

klp396@nyu.edu,snschieffer@comcast.net,

knh190@hotmail.com,vrt226@stern.nyu.edu, meredithsuewillis@gmail.com

Double space your homework and presentation pieces (for readability)

Please give everything page numbers.

SIGN UP TO PRESENT! I hope for two presentations for each of you, at least those who want them. Do try for at least one--it's good for you and your novel!

Next week: Kea Pedersen and Marie Constanza present.

Presenter work due Sunday night

Homeworks due by midnight of class day. Thus homework for 10-4-23 is due midnight 10-4-23. I'll return homeworks by the next class day.

Please let me know how you plan to give me up to 50 pp. You don't have to do 50, but I'd like to know roughly when I'm getting what.

Everyone is down for one presentation. If you want a second and don't' have it yet, let me know ASAP! One option is a few extra pages on the day you are signed up for.

Any questions on business at this point?

II. Leftover from last week:

1. A Point of view problem example: "The Thriller Bar Scene."

2. Time frame/span: Think about what I call the " present time of the story" for your novel. This is for your process not for the reader.

What is the chronologically farthest forward time? That is, not back story, not flashbacks, etc., but chronological time going forward. The present time of James Joyce's novelistic long story "The Dead" is the 5 or 6 hours of a party followed by a carriage ride to a hotel to sleep--plus a a lot of the past given in memories, dialogue, and narration. The present time might be one instant as a man remembers his life before the firing squad releases the bullets; the thirty-five year old narrator in an unspecified present goes back over her growing up in long dramatized scenes.

This is useful as you structure your novel: having a "present time of the story" and a chronology of events can help you keep organized.

II. WRITE: A Macro Exercise

I promised we'd be going macro and micro-- here's a Macro exercise about the novel you are planning/engaged in. This is a structuring exercise, to get a grip on the novel-as-a-whole. We touched on these first session, but more here. Answer these questions about your novel, the first are one word or number answers:

Short answers:

– What genre? (Fiction autobiography? Para normal Romance?)

– How much is done written so far?

– How long will it be when it's finished?

-- Who is reading my book? Where? What format?

– Some books I think people would like who would like my book– the way Barnes & Noble stores have a shelf of “If you like this one, try this."

This next should be a few sentences:

– Someone has written a review of your novel. They describe its best quality-- and an area where it could be improved!

III. Discuss the exercise (briefly)

IV. Presenter One

Marie Constanza

V. Go-Round--where we areHalf of How's-it-going go-around. Setting aside time? "Challenges?"

VI. BREAK

VII. Presenter Two

Paul O'Malley

VIII. Mini lecture on dialogue

We are talking today about how dialogue works. We all know what it is. BUT for novel writing: Dialogue is where the drama is-- conflict, confrontation, love!

It is also the closest thing to "real" time as anything in prose narrative. A sword thrust in fiction isn't much like one in life or movies. But dialogue is.

On the other hand, we have to make an illusion. The transcription of a real dialogue too long and boring. Our job is to create the illusion of people ;speaking.

Types of Discourse: all useful and common in novels and other conventional fiction.

Dialogue Tags Try to minimize drawing attention to them for momentum and pacing of the story. Check out this article, if you haven't yet: Avoid Creative Dialogue Tag Syndrome."

A little dialogue and a lot of "enriching" material: from Yonnondio

IX. More Dialogue

If it isn't natural to you, a good technique to try is to write down JUST THE WORDS SAID, then go back and add:

setting

descriptions

tags

modifiers to the tags

some inner monologue

If you haven't seen it yet, see from Yonnondio

And then go back a third time and cut away everything that isn't interesting!

X. WRITE

See if you can put this in your novel.

Hi.

Hi.

I guess this is it.

I guess it is.

Then enrich it with settingk descriptions, modifiers, inner dialogue--whatever. But try to start with the skeleton of words and then the sense details and narration.

XI. Finish Go-round on where we are

Second half of How's-it-going go-around. Setting aside time? "Challenges?"

XII. Assignments For next week:

Writing Assignment:

Finish the in-class writing dialogue: Try to have this be from somewhere in the middle or the novel

Or, substitute a passage from your novel you want feedback on.

Reading/Listening Assignments (Some of these are repeats, in case you didn't check them out yet):

Student presentations coming by e-mail attachments.

Dialect Issues: Ed Davis's article in the Writers Digest's Blog about writing dialect.

Dialect Samples

Dialect Issues: Ed Davis's article in the Writers Digest's Blog about writing dialect.

Dialogue in Two Languages

Read possibly the greatest summary in twentieth century literature--told not shown!--from Virginia Woolf's To The Lighthouse, the death of Mrs. Ramsay. The bracketed "scene" is as Woolf wrote it.

Scene and summary. What is Scene? Why is it important? The building block of novels. Some ways of telling a story– central one is scene. Please be sure and read the things online about scene, but in a nutshell, it's the unit of the novel–not the only thing, and some novels it isn't even the main thing, but always crucial for drama, for the reader visualizing the action.

10 Tips for Strong Scenes (from Masterclass.com (optional)

Ten Strategies, "Strategy 5: Master Dialogue and Scene" (optional)

An eleven minute recorded mini-lecture by me on Scene (optional)

Session 4

10-4-23

Scene & Dialogue II:

Monologue (inner speech), Group Scenes

Presentation/Critique

Schedule

For an overview of weekly topics, click here.

ASSIGNMENTS DUE 10-4-23:

Writing Assignment:

Finish the in-class writing dialogue: "It's Been a Long Time..." Try to have this be from somewhere in the middle or the novel

Or, substitute a passage from your novel you want feedback on.

Reading/Listening Assignments (Some of these are repeats, in case you didn't check them out yet):

Student presentations coming by e-mail attachments.

Dialect Issues:

Ed Davis's article in the Writers Digest's Blog about writing dialect.

Dialect Samples

Dialect Issues: Ed Davis's article in the Writers Digest's Blog about writing dialect.

Dialogue in Two Languages

Read possibly the greatest summary in twentieth century literature--told not shown!--from Virginia Woolf's To The Lighthouse, the death of Mrs. Ramsay. The bracketed "scene" is as Woolf wrote it.

Scene and summary. What is Scene? Why is it important? The building block of novels. Some ways of telling a story– central one is scene. Please be sure and read the things online about scene, but in a nutshell, it's the unit of the novel–not the only thing, and some novels it isn't even the main thing, but always crucial for drama, for the reader visualizing the action.

10 Tips for Strong Scenes (from Masterclass.com (optional)

Ten Strategies, "Strategy 5: Master Dialogue and Scene" (optional)

I. Business

One more time: corrected email list:

philipai@verizon.net,labestseller@optimum.net,kristennballard@gmail.com,mcc1@nyu.edu,

jackiedorward@gmail.com, beatrizcosta.fontes@gmail.com,alexisgogh@gmail.com,

birgitmatzerath@gmail.com,1980pom@gmail.com, klp396@nyu.edu,snschieffer@comcast.net,

knh190@hotmail.com,vrt226@stern.nyu.edu, meredithsuewillis@gmail.comOnly a few people don't have second sign ups. If we get into four a session, there will be shorter discussions.

Non-evaluative Grade Information: if you don't want a grade, you must follow these instructions. Or just get in touch with Kenneth French at kenneth.french@nyu.edu

- Don't forget to use editorial proofediting marks if you are writing on papers by hand. There are many links to show these on th 'net. Here's one: Northwestern U. Proofreading Marks.

- Next week: Alexis Gogh and Victoria Tralies present.

- Any questions on business at this point?

II. Discussion -- Finish go-round on how my novel is going....

III. Write:Put some feet in your novel. Main character studying own or someone else's-- getting a pedicure; feeling of feet during a run or with uncomfortable shoes, watching feet on a subway and thinking, or anything else with feet. Ugly monster feet about to attack, sweet-smelling pink-soled baby feet.

IV. Presenter One

Kea Pedersen

V. BREAK

VI. Presenter TwoMarie Constanza

VII. Mini-lecture on scene ONE

Dialect is the dramatic heart, but scene is the building block, the essential structure of a novel.

In common speech, "scene" is the place where an action or event occurs, such as the scene of the crime. It is also commonly used to refer to a public display of passion or temper as in, "She tried not to make a scene." It is also a sphere of activity, as when we speak of observing the political scene. In slang, it is a situation or set of circumstances– "a bad scene.

In theater, film, and novel, it is an essential unit of action. In drama, there is a new scene when a new character enters. The setting is fixed and the time continuous, usually "real" or natural time. In film, a scene is a shot or series of shots constituting a unit of continuous related action. In the novel, it is above all a dramatized moment– shown, not told. It can include dialogue, monologue (thinking) description, action, etc. etc. The dynamics change. People talk and act. Something happens.

We remember great scenes in movies and novels.

In fiction, while there are lots of things besides scenes– passages of narration and long internal monologues, for example– most writers eventually come to the point where they want to dramatize their story with a scene. Dialogue or other interaction between two or more characters often marks the heart of a scene. You can have pages and pages of narration, or pages and pages of the vicissitudes of one character's thoughts or suffering, but the building block of fiction is a series of scenes with connecting and surrounding material.

The sene is the way the story moves to its next level: this is where the other parts of the story come together; or, it may be the beginning of everything, after which the next parts deal with the repercussions of this dramatized part.

A scene is "dramatized," although not necessarily dramatic in the sense of having a lot of shouting or overt action. It generally demonstrates or "shows" rather than tells.

One excellent way to outline a novel is to list twenty or thirty scenes--and then write them.

One of the optional readings I suggested for today was 10 Tips for Strong Scenes (from Masterclass.com. This is worth looking at but it, like so many articles for writers, is really about revions--the product--rather than the preocess of drafting. So look at it as some good ideas for critiquing or revising your work.

VIII. Write or Think of the five most important scenes in your novel. List them. If you don't know them already, make them up.

IX. Anything you want covered in the next weeks? Please email me.

X. Assignments for next week:

Writing assignment:A fleshed out scene in your novel (dialog,setting, characters, maybe thought etc.) that includes FEET (or other body part)

Or substitute anything yhou want feeback on from your novel.

Reading assignments:

So-called "inner dialogue" or monologue (from Editor's Blog).

A Man Told Me by Grace Paley A short short story that is a single scene in the form of a monologue.

Reedsy's six "unbreakable" rules for dialogue punctuation.

Just for fun: Fifty-very-bad-book-covers-for-literary-classics

(Optional) In Ten Strategies read "Strategy 6: Structuring Your Novel," pages 77-96.

Presentation Schedule

Session 5

Catch-up On Scene;

Structure I: Plot, Story, Architectonics

Structures for novels: architectonics (Moynihan Station); Big Bins; Episodic epics (The Odyssey)

Assignments for this week:

Writing assignment:

A fleshed out scene in your novel (dialog,setting, characters, maybe thought etc.) that includes FEET (or other body part)

Or substitute anything you want feedback on from your novel.

Reading assignments:

Reedsy's six "unbreakable" rules for dialogue punctuation.

So-called "inner dialogue" or monologue (from Editor's Blog).

A Man Told Me by Grace Paley A short short story that is a single scene in the form of a monologue.

Just for fun: Fifty-very-bad-book-covers-for-literary-classics

(Optional) In Ten Strategies read "Strategy 6: Structuring Your Novel," pages 77-96.

I. Business

- Please let me know if you don't get back a homework or critiqued presentation piece from me!

Jackie Dorward is STILL not getting e-mails. Please! Everyone! Now! Change her e-mail address on your class list to Jackiedorward@gmail.com.

- Don't forget to use editorial proofediting marks if you are writing on papers by hand. There are many links with these on the 'net. Here's one: Northwestern U. Proofreading Marks.

- Non-evaluative Grade Information: if you don't want a grade, you must follow these instructions. Or get in touch with Kenneth French at kenneth.french@nyu.edu

- Next week: Paul and Lingxiao do second presentations.

- Also, I'll be sending a link to a google form for my self-evaluation/course correction. Just four or five short questions.

- Dialogue punctuation: Start with all of one character's speech, gestures, thoughts, in one paragraph. New paragraph for a new speaker (and the speaker's thoughts, actions, etc.) Don't make a new paragraph unless there's a new person directly quoted. See Reedsy's 6 "Unbreakable" Rules on Dialogue Punctuation.

II. Mini-lecture on scene PART TWO (leftover from Session Four):

A. Strategies for group and crowd scenes

Here are a couple of practical strategies for dealing with logistics and large groups. Not tricks-- all prose narrative, after all, is an illusion of reality-- but as you revise your enthusiastic, energetic, hasty first draft, you might try these things to make the storytelling run more smoothly.

Group scenes are notoriously tough to write--this is an area movies do well, and novels can do well, but they take some revising.

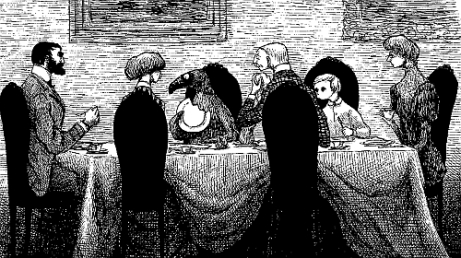

Edward Gorey dinner scene; strike from Zola's Germinal

- Master Strategy: Be very clear on the point of view, not just character but actual position of the story teller. Where is the teller standing? Clarify the logistics and physical action by giving a firm point of view. Imagine a fixed camera or a character standing next to a van in the northeast corner. Write only what is seen from that point of view. This will help keep the reader --and you the writer--oriented. Even if you have a multiple viewpoint story, write your action and crowd scenes from a fixed point of view.

- In a large crowd scene, only identify two or three individuals. Say "The twenty two members of the Ridgewood Bobcats walked into the dressing room with long faces," and then give quoted speeches only to Rob, Andrei, and Coach. The other Bobcats can mutter as a group, or hang their heads in shame, but they remain a mass, part of the scene setting.

- As above. only give proper names to the most important characters in a group scene. (Be sure you really need the names. Proper names call attention to themselves, slow down the flow of the story.)

- Conflate. If you are writing fiction based on, say, your own large family, conflate two annoying little brothers into one. It strays from the facts, but allows the creation of one full character and eases your logistical problems.

B. Monologue and minor characters. Click here.

Monologues are one of the best ways to explore character— both for the writer and the reader. In first person fiction or in a memoir, you can have a secondary character tell a story about herself/himself in dialogue.

When I reread Dickens, I am consistently blown away by the minor characters who pop up it seems on every page. Some of them are mere sketches, and many are two-dimensional, but Dickens often has them tell quite long stories about themselves. Thus, a monologue can be simply a long speech in dialogue. Two people are, say, having a drink, and one starts telling his life story.

Or, the main character might receive an e-mail or letter from a minor character. A friend of mine is writing a memoir, and she has a cache of old paper letters between her mother and father which she is using generously in order to give her parents, of whom she is often critical, an opportunity to speak for themselves. This is a good way to learn more about a character who feels a little flat.

Large or small snatches of the first person or close third person main character's thoughts work very well in fiction and come naturally to many of us. For those who like categories, this is a variety of Free Indirect or Free Direct Discourse. (See types of discourse here.)

How to punctuate these passages of thought or "inner dialog?" Here are some alternatives:

Joey looked at the two women who he now realized were only posing as his long-lost cousins. Stupid ignorant fool, he thought to himself. Should have known better than to hope...

Joey looked at the two women who he now realized were only posing as his long-lost cousins. Stupid ignorant fool, he thought to himself. Should have known better than to hope...

Joey looked at the two women who he now realized were only posing as his long-lost cousins. Stupid ignorant fool. Should have known better than to hope...

The one thing not to do, in order to avoid confusion, is not to use quotation marks. We generally reserve those for spoken, direct dialogue.

III. Presenter One: Alexis Gogh

IV. WRITE

Macro exercise: We're going to start talking about how you structure your story. Here's a little macro exercise. Tell your whole novel (making it up if you don't know what's going to happen--a hypothetical plot is a good exercise) as a paragraph long story. Narrate it as if it were a parable or myth or fairy tale. Start with something like, "There was once a young person who..." or "In the second decade of the twenty-first century...."

Keep it short, and don't worry about what you're leaving out. Just write the essentials. The essentials are the point of the exercise. And definitely tell what happens at the end. You are not committed. This is an exercise. This is only an exercise...

Example:

There were once two sisters whose mother was sent away and whose father was never there. They made a world of their own and sometimes included the little boy next door. When they all grew up, they separated, but the little boy next door became powerful and rich. He wanted to recapture the happy times. He built a special house just for the sisters, but once they got there, they thought it was a trap and ran away. Some of his soldiers turned against him and robbed him but the sisters found him and fed him, and gave him shelter in a little house in the woods near where they lived.

That's a pretty bad summary of my 2018 novel Their Houses. It reminds me that the heart of my story, which in spite of a lot of characters and time passing, all hinges on this threesome and their search for shelter and emotional nourishment.

V. BREAK

VI. Presenter Two: Victoria Tralies

VII. DISCUSS .... your favorite or most admired novel: How is it structured? Its Architecture?

Examples

Freitag's pyramid (probably too simple for a novel)-- but it can be helpful to think about how your story moves.

VIII. WRITE:

Put something green in your novel. This is a scene-starter: someone notices, eats, describes, is attacked by--something green! Begin with a description of the green thing (mold on old bread? An enemy's headgear? a view out the window?) and then see where it takes you. Write the scene.

As usual, this works best for something farther forward that you haven't written yet, but feel free to expand an existing scene.

IX. MINI LECTURE: Beginning to Think About Structure

The brief narrative of your novel was one way. Another way is architectonics (the roof of Moynihan Station above) or episodic like The Odyssey or a common large pattern like a life story. Tons of these: a chronological life story; a story of coming to adulthood (bildunsroman); the story of a summer; the story of the arc of a friendship or love affair.

I'm working on a short, probably y.a. novel called The Old Lady Girl which started out as part of a series of short stories called Feral Grandmothers. I have written this episodically, just sort of sending the girl off for the summer with her father, and then finding what happens. I used writing as the way to find the story, and presently I'm taking that loosely drafted version to "really writing it."

If you have a lot of ideas but haven't yet gotten a real story line going, try Big Bins.

These bins are a way to do a first organization of your material, if it doesn't fail into a natural story line or pattern. The idea is to come up with a very large pattern and collect the appropriate materials in the bins. You may use these just for organizing, or they may become actual sections of your novel. Thus:

Part I--1908; Part II World War Two; Part III--the Sixties; Part IV-- 2000; Part V--the Present.

Or, Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter

Or, New York, Paris, New York.

Or, make a bin for each important character (each section has a pov character for say 50 pages);

Etc. But always big stuff: time, place, human beings.

X. Homework for next week

Writing Assignments:

Choice:

1. Finish the in-class writing: put something green in your novel. This is a scene-starter: someone notices, eats, describes, is attacked by--something green! Begin with a description of the green thing (mold on old bread? An enemy's headgear? a view out the window?) and then see where it takes you. Write the scene. As usual, this works best for something farther forward that you haven't written yet, but feel free to expand an existing scene.

2. A crowd scene from your novel.

3. Substitute!

Reading Assignments:

- Read Outlining from Ten Strategies (selections from Chapter 6)

- OPTIONAL: In Ten Strategies, read in "Strategy 6: Structure Your Novel." page 96 - 102, "The Best Time to Start Outlining." (optional)

Presentation Schedule

Session 6

Structuring Your Novel II:

More Logistics; Story Arc and Plot;

How to Make Outlining Work for you

Presentation/Critique Schedule

For an overview of weekly topics past and future, click here.

Assignments due for 10-18-23:

Writing Assignments:

Choice:

1. Finish the in-class writing: put something green in your novel. This is a scene-starter: someone notices, eats, describes, is attacked by--something green! Begin with a description of the green thing (mold on old bread? An enemy's headgear? a view out the window?) and then see where it takes you. Write the scene. As usual, this works best for something farther forward that you haven't written yet, but feel free to expand an existing scene.

2. A crowd scene from your novel.

3. Substitute!

Reading Assignments:

- Read Outlining from Ten Strategies (selections from Chapter 6)

- OPTIONAL: In Ten Strategies, read in "Strategy 6: Structure Your Novel." page 96 - 102, "The Best Time to Start Outlining." (optional)

I. Business

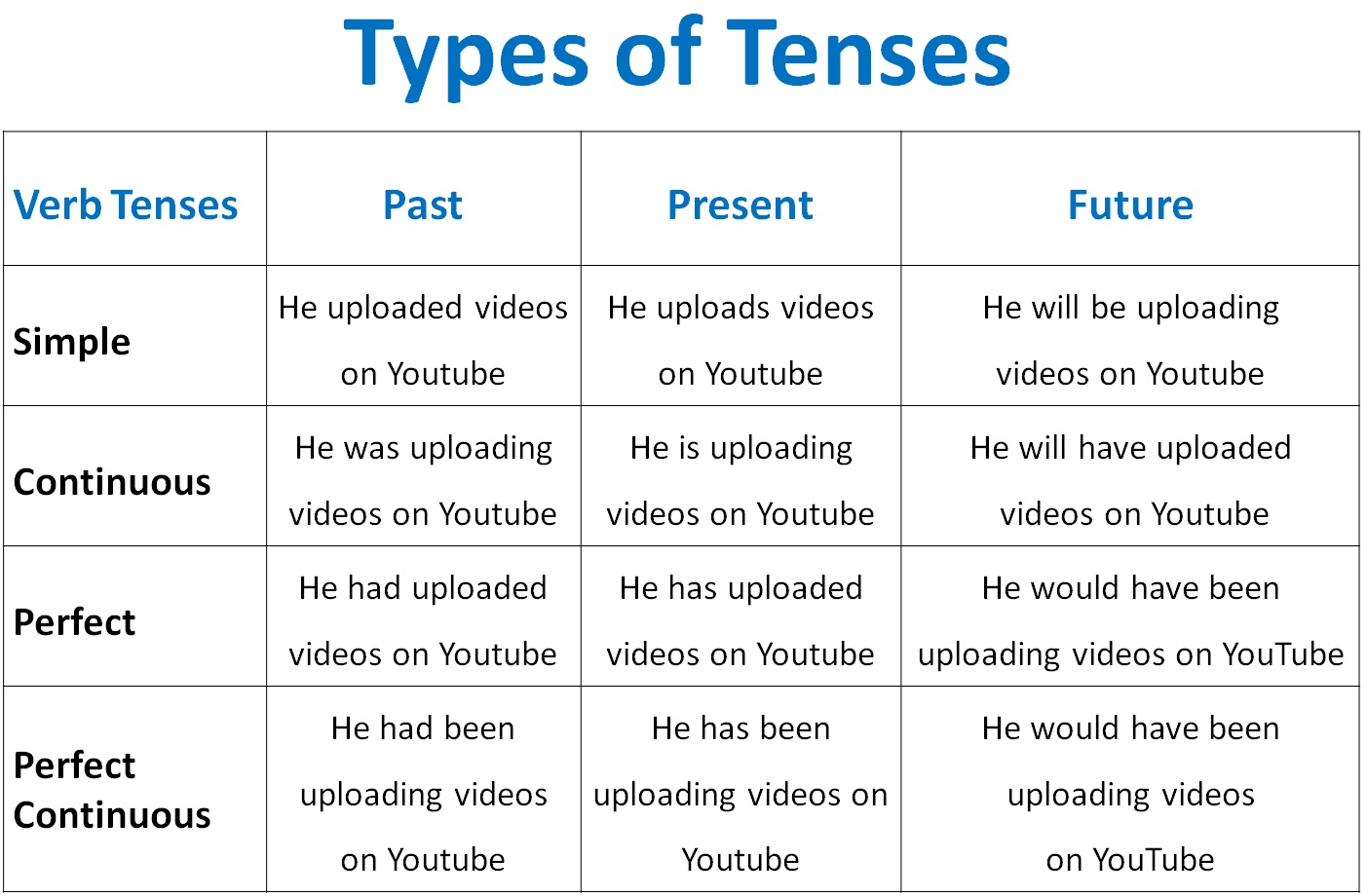

- Moving a discussion of Time and Tense to next week

- Repeat: please let me know if you don't get back a homework or critiqued presentation piece from me!

- Non-evaluative Grade Information: if you don't want a grade, you must follow these instructions. Or get in touch with Kenneth French at kenneth.french@nyu.edu

- Next week: Susan and Linda present--presentation pieces should arrive by Sunday night.

- Does anyone want in the final sessions a short What to Do When You Finish Your Novel?

- Evaluation/ Course change just for MSW has been sent out. Did you get it?

- Book List of well-structured books from the class:

Matt Haig - The Midnight Library

Nick Hornby - High Fidelity

Taylor Jenkins Reid - contemporary author of Daisy Jones & the Six, Seven Husband of Evelyn Hugo, Malibu Rising

David Nicholls - One Day - Each chapter happens on the same date over 20 years

Every Summer After by Carley Fortune

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue by VE Schwab

Other books that play with the concept of time and have multiplot structures: anything by David Mitchell (Cloud Atlas, Bone Clocks, etc.)

Lark and Termite by Jayne Anne Phillip;s

Classics: War and Peace (alternating sections about war–and peace!)

II. A couple of minutes on logistics.

We talked last week about group scenes and being clear about things like where the narrator or point of view character is standing, about imagining a fixed camera or a character standing next to a van in the northeast corner of the plaza. Write only what is seen from that point of view. This will help keep the reader --and you the writer--oriented. Even if you have a multiple viewpoint story, write your action and crowd scenes from a fixed point of view.

Here are some examples: A classic news article; The Drunken Cowpoke; a scene that I think Linda mentioned from one of my novels in a big dining room.

Logistics also includes physical action: Sample from Lee Childs. Is it too much? In novel, it's at a tense moment, so it's building suspense. Also note the way he starts fairly distant from the third person limited character, but then slips deeper and deeper in: the short sentences, feelings. More and more interior.

III. Write:

Logistics of physical action

One of your characters is climbing, and it is difficult for the climber. This can be about the main character or someone the main character is observing. If you are writing in third person, describe the action, if close third person of first person, include how it feels. This can be climbing a ladder and being afraid; rock climbing as a sport; a desperate climb to escape. It can even be a toddler "climbing" to its feet after a tumble. Mainly, make it something from your novel.

IV. How was that? Share?

V. Discussion Part I

What do you feel you need to work on/do next. I'll go first. I have a rough draft, and I'm doing what I call "real writing." That is, I've made what amounts to my own formula, my story is there, and now I'm enriching, going deeper, cutting, moving. I actually held myself back a little to get the story out there, to get the dialogue fast moving. Now I'm going as slowly as I want. Still not editing. This is what I've called "Deep Revision."

VI. Presenter One

Yu Lingxiao

VII. Mini Lecture on some forms, shapes and structures for novels:

Generally, to oversimplify greatly, stories are simple. often linear (or linear with flashbacks or linear after we find out the ending) and everyone uses the same ones: a life story, a love story, a quest, Jane Austen's marriages to tie up loose ends, etc.

Plot is more knotted up, more clever. The plot is full of meet-cute, clever misunderstandings, tensions, etc.

Many, probably most, have both plot and story: perhaps a whodunit overlies a coming to maturity of the sleuth.

Some Classic story shapes would include a question to answer; a violent act and consequences; a situation and then the story of how we got there. Thus typical story forms are:

from problem to solution –

from mystery to solution –

from conflict to peace –

from danger to safety –

from confusion to order –

from dilemma to decision –

from ignorance to knowledge

And their opposites.

We talked last week about creating some big bins or structures to hold your drafted material. There are also common patterns like the Hero's Journey and Multi-plot novel.

One I particularly like, especially for early drafting, is to collect scenes and then list them in a tentative order like an Archipelago. You would, if you haven't yet, write these scenes, then go back and make a draft of the novel from beginning to end, adding more scenes and connecting material.

This, sailing from island/scene to island/scene, is how the Polynesian explorers populated the Pacific ocean.

The Archipelago method of structuring your novel

VIII. BREAK

IX. Presenter Two

Paul O'Malley TWO

X. Discussion Continued

What do you feel you need to work on/do next. I'll go first. I have a rough draft, and I'm doing what I call "real writing." That is, I've made what amounts to my own formula, my story is there, and now I'm enriching, going deeper, cutting, moving. I actually held myself back a little to get the story out there, to get the dialogue fast moving. Now I'm going as slowly as I want. Still not editing. This is what I've called "Deep Revision."

XI. Mini Lecture on the uses of Outlining:Whether, When, and What instead?

How many of you already have an outline?

Outlining: when to do it? Simple answer is after your've drafted 50 to100 pages, as a way to see what you've got and where you're going.

I am personally partial to three methods (but the main thing is, DO IT AFTER YOU HAVE DRAFTED SOME and FIND ONE THAT WORKS FOR YOU!

– the Archipelago method I already talked about.

-- the hypothetical method for creating a plot: you make up a hypothetical or test plot. Write down a beginning, middle, and end. Write as if that made-up plot were your plot, but be ready at any moment to change it. This gives you a structure to work with (especially an end point) but gives preference to changes that your imagination might come up with.

– The chronological outline--useful however else you outline or structure.

– The "running outline," which is a daily record of progress and changes.

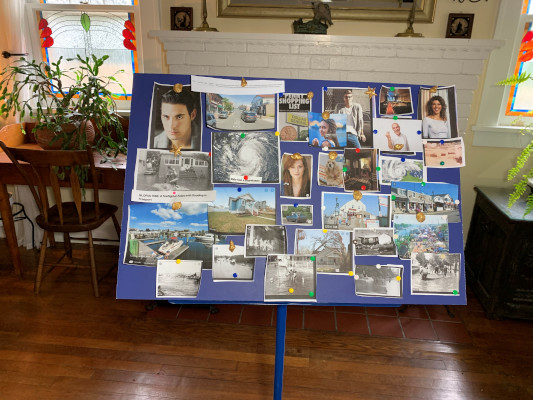

– Here are some samples: Note re: my sample outlines that one is a form that a writer created to help draft each chapter in the book. One is from my non-fiction book about writing a novel, which is fairly straightforward, based on teaching and workshops I've done, and much less of a struggle than my fiction outlines. . Another is from a science fiction novel of mine, and it's what I call a "running outline," that is, I update it at the end of a day's work--doing the page count, word count, date, and also making any changes (names, facts) that I came up with that day. One is a student "outline" that is really a diagram of characters that helped her in her thinking--and that's the main point of an outline: to help you visualize what you've done and to hypothesize about what you might do--and remember ideas for the future. You need to find your own best outlining method. Here is one that is bulletin board for thinking:

The "Penny Board"

More Outline Samples and ideas:

Character Diagram Outline Time line outline

Vision Board of a Novel using real-life materials to stimulate ideas

X. Assignments for 10-25-23:

Writing Assignment:

1. The scene with climbing in it.

One of your characters is climbing, and it is difficult for the climber. This can be about the main character or someone the main character is observing. If you are writing in third person, describe the action, if close third person of first person, include how it feels. This can be climbing a ladder and being afraid; rock climbing as a sport; a desperate climb to escape. It can even be a toddler "climbing" to its feet after a tumble. Mainly, make it something from your novel.

2. Write a short outline of your novel using any of the methods we've discussed: Draw a picture, do a time line, a Venn diagram. Make up your own.

3. Any scene you'd like feedback on

Reading and Other Assignments:

More ideas on outlining and structuring:

Please return the evaluation form.

Beat Sheet

"Stakes" Method of Outlining

Best Seller: How to write one: from James Scott Bell, a thriller writer and lawyer, has a course at the Great Courses on writing a best seller

Malcolm Gladwell on the four types of detective/mystery.thriller novels.

Check out Harvey Chapman's Novel Writing Help. He's an oddity who seems to me more interested in how fiction works (and teaching it) than in writing it. He has a gruff self-consciously masculine style, but is definitely worth a look.

The Raised Relief Map-- a drafting technique for creative write

PRESENTATION SCHEDULE

Session 7

10-25-23

Tense, Time, & What To Do

When You've Finished Your Manuscript.

Assignments for Today 10-25-23:

Writing Assignment:

1. The scene with climbing in it. One of your characters is climbing, and it is difficult for the climber. This can be about the main character or someone the main character is observing. If you are writing in third person, describe the action, if close third person of first person, include how it feels. This can be climbing a ladder and being afraid; rock climbing as a sport; a desperate climb to escape. It can even be a toddler "climbing" to its feet after a tumble. Mainly, make it something from your novel.

2. Write a short outline of your novel using any of the methods we've discussed: Draw a picture, do a time line, a Venn diagram. Make up your own.

3. Any scene you'd like feedback on

Reading and Other Assignments:

Check out NaNoWriMo! (November is National Novel Writing Month!)

Please return the evaluation form.

More ideas on outlining and structuring:

Beat Sheet

"Stakes" Method of Outlining

Best Seller: How to write one: from James Scott Bell, a thriller writer and lawyer, has a course at the Great Courses on writing a best seller

Malcolm Gladwell on the four types of detective/mystery.thriller novels.

Check out Harvey Chapman's Novel Writing Help. He's an oddity who seems to me more interested in how fiction works (and teaching it) than in writing it. He has a gruff self-consciously masculine style, but is definitely worth a look.

The Raised Relief Map-- a drafting technique for creative write

I. Business

- Next week: Three Presenters--Linda, Beatriz, and Alexis. Second Presentaions. Pieces should arrive by Sunday night.

- Evaluation form. Only three responses so far. My idea is to use the suggestions, so please respond sooner rather than later. A couple of ideas: one responder wanted more discussion on others' approach to novel writing; one wondered about one-on-one time with the instructor; another about how to know when the book is ready for reaching out agents, etc.; and, how about for suggestions for other courses?

- For those interested in more classes and workshops, summer conferences etc., take a look at my Resources for Writers page. Also, consider subscreibing or buying a hard copy of Poets & Writers. Lists of conferences, services, contests, and more. Good stuff, highly recommented. Online, Newpages.com has a lot of resources.

- Other business, questions?

II. From last week:

1. Tense

About the Present Tense:

From "Article on Pros and Cons" by David Jauss belowi: [Present tense has become the default choice for many younger writers.] "Recently, I asked one of my talented undergraduate students why she wrote all of her stories in the present tense. 'Isn't that the way fiction's supposed to be written now?' she said, then added, 'The past tense makes a story seem kind of 19th-century, don't you think?'"

Immediacy versus complexity of character

Now only versus manipulations of time.

Emphasis on small present details versus a long view

If you haven't read these yet, you may want to:

MasterClass on Writing a novel in the Present Tense

Article on Pros and Cons of Present Tense

2. Just a Little On Time in novels:

Novels do manipulation of time perhaps better than any other art form, using strategies like flashback, foreshadowing, and special techniques like ellipsis, summary, scene, stretch, and pause.

We talked a lot earlier about scene, which is the showing rather than telling of what is going on. I always speak of it as the quintessential building block of the novel. It is the central way we move novels forward, and I suggested that one way of drafting is to make rough versions of the 5 or 17 most important moments in the novel. This is the closest we write to real time.

To stretch or pause time, on the other hand, allows us something all human beings seek, which is to stop and examine what is happening in detail, or to hold something that is precious or beautiful or shocking or terrible frozen for a while--or to get a second chance, a do-over.Even to change what happened by going back in or stopping time.

Here are some more of the specific manipulations we use:

Flashback is not just "I remembered how we used to drink lemonade on summer nights," but when we stop the forward motion (the "present time") of our story and actually describe the flavor of the lemonade, quote what was said, write a whole scene that is as full and rich as a scene in the present of the novel.

Foreshadowing is useful in certain kinds of novels, often as a means of building suspense: here's the opening of Dennis Lehane's novel Live by Night:

Some years later, on a tugboat in the Gulf of Mexico, Joe Coughlin’s feet were placed in a tub of cement. Twelve gunmen stood waiting until they got far enough out to sea to throw him overboard, while Joe listened to the engine chug and watched the water churn white at the stern. And it occurred to him that almost everything of note that had ever happened in his life—good or bad—had been set in motion the morning he first crossed paths with Emma Gould.

Is Lehane manipulating us here ? Grabbing our attention? Sure, and we are pretty darn happy to be manipulated.

Memory, in its various forms, but especially when sense impressions usefully set off (and transitioning to) memories. (see Proust's À la recherche du temps perdu !)

Dreams and visions. To be used sparingly, but can be very effective in in novels becuase we engage the reader's mind and imagination.

III. WRITEA moment in your novel that you have already written. Try it again, without reference to your draft, but in a diffeerent tense and/or person. That is, instead of "Long ago, when I was seven and had just begun to read books...." try "I am seven years old and I have just begun to read books..." Or, perhaps, "She was about seven, the little girl carrying so many books in her arms that she stumbled from the weight" versus "I am seven years old and I stumble sometimes in in the library because I have so many books!"

IV. PRESENTER ONE: Linda Atlas

V. Marketing Mini-lecture

If you haven't looked at yet, I have a Resources for Writers Page and a .pdf of Draft Notes on Getting Published. The best overview I know is Jane Friedman's How to Get Your Book Published article.

A. Marketing and Publishing: A few notes, but come back for the links.

1. Today is a time of great flux--lines weakened between commercial publishing and so-called indie publishing (sometimes self-publishing, sometimes hybrid or subsidized or cooperative publishing). There are many models for publishing today, but making a living at it is less and less likely.

Returning to the Chaucer/Shakespeare/Jane Austen models?

There is a great deal of competition for the entertainment dollar!

2. The ideal, which I came in at the very end of, is that you get a literary agent who takes on book, sells to editor, who sells to her publisher, who edits, prints, sells, etc. You market your work to the agent (very genteely!), then the business is taken over by professionals. You were not really expected to "market" the finsihed product--maybe an all-expenses paid book tour.

3. The present: Now, however, even with commercial publisher, authors are usually asked for a "platform" and sometimes to pay for their own copy editing and publicity.

4. "Independent" publishing has replaced "self" publishing, and it is not looked down upon nearly as much. It probably should not be your first choice though.

Personal: I have had various agents, but at present work without one. Even when I had a hotshot agent for 17 years, who placed my first novel with Scribner's, I placed my children's and literary short story book on my own. The agent just went over contracts and took her cut. Since my first three commercial novels, I've published with

another major New York publisher (children's novel)

several small presses that pay little or nothing

university presses that don't do advances, but do pay royalties

a cooperative press where writers share work and pay their own expenses

5. The world of e-book publishing without hard copies is a whole other kettle of fish: E-publishing is amazingly cheap, with often amazingly bad writing, and, especially with certain genres, has become a common outlet.

B. Give your first energy to getting your story and the words it's written with in excellent condition.

Then, as you approach the end, begin to do some research.

Check out these Draft Notes on Getting Published.

For an excellent outline on the basics of getting published, look at Jane Friedman's page and her blog.

Excellent general resources on places to submit, lists of writing programs and conferences and much, much more: NewPages.com and Poets & Writers. Also excellent site for general information (literary agents, for example,)is Duotrope.com.

Here's a short paper on submitting to university presses by Danny Williams,

MSW's Resources for Writers has a lot of odds 'n ends.

Especially for literary writing, see Poets & Writers.

Notes on various types of publishing at Publishing Types and Print on Demand.

How long should a novel be? See notes on my Resources for Writers page.

A one-pager, somewhat out-of-date, of resources about getting published

See blog post by Veronica Sicoe on why she self-publishes.

A Wall Street Journal article about Marlen Bodden, a former student in one of my novel classes who first self-published-- and then had her book picked up by a commercial press. Note: self-publishing should never be you first choice, but it should be on your list of possibilities.

Another good resource: An online magazine called AuthorsPublish at https://authorspublish.com/ . Here's their free guide to traditional-style publishers who don't require agents.

C. Do these things as you feel ready to market your novel

First, get the manuscript in pristine condition--editors don't have patience for mess and mistakes. The competition's too great. Have friends and even family read all or part of it. All readers have something to say. Someone totally un-literary may be great proof-editor.

Experiment with submitting to online journals, magazines, & contests--short stories or novel-parts, or sections of your novel that can be edited to stand alone. This can be useful when you try to get an agent or editor, evidence that someone else appreciated your work. There are infinite possibilities on the Internet and also look at NewPages.com. Most online and other literary journals don't pay. They are, however, easy to submit, using something called "Submittable." Note also that many of them charge a reading fee of $3 and up.

On Facebook, search for "Calls for submissions (poetry, fiction, art." Sign up to get notices.

Peruse old standards like Writer's Market and The Writer and Writer's Digest and get on Jane Friedman's free newsletter list. Read Jeff Herman's Guide to Agents.

Lots of good stuff, oriented toward literary writing, at Poets & Writers.

Consider going to a writers' conference to make connections and learn more. Some people love these, but even if you don't, one conference should give you an overview and the vocabulary you need to proceed. And doing no writers' conferences is just fine too.

D. Any Specific Questions?

How do you copyright your novel to prevent someone from stealing the ideas and content? Go online to http://www.copyright.gov for the latest information. HOWEVER, from the moment you finish a piece of writing, the government recognizes that only you can decide how to use it. The law presently governing this is the copyright law of January 1, 1978. A piece of writing is copyrighted the moment you create it, You may indicate your authorship with the word Copyright (or the c-in-a-circle sign), the year, and your name, but this is not necessary. Protection lasts for your lifetime plus 50 years. If your work is anonymous or pseudonymous, protection lasts for 100 years after the work's creation or 75 years after its publication, whichever is shorter. None of this holds in the case of writing-for-hire. You do not have to register your work with the Copyright Office to receive protection. If you want to, however, you may request the proper forms from the Copyright Office, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20559

VI. BREAK

VII. PRESENTER TWO: Susan Scheiffer

VIII. Thinking Exercise:

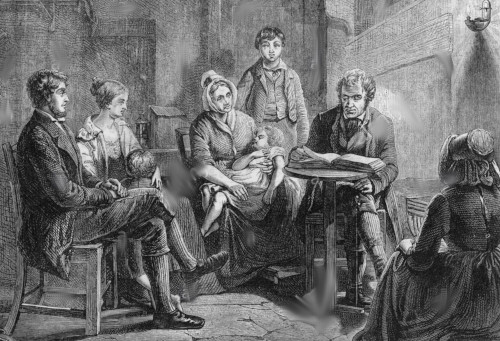

This is a structure exercise, about finding the center, the most crucial turn of the story--like the climax of a a plot and analogous to (but not the same as) "the main idea" or "what it's about." A novel may, of course, have several of these, especially if it has several strands of story. Pretend your novel is being published in the 19th century, when illustrations were common in good editions of novels--lovely line drawings. The novel will have a frontispiece, an illustration of an important moment in the novel that attracts a potential reader

First, Describe the black-and-white illustration as it would appear in the front of the novel

Then, Write the scene.

IX.

Homework for 11-1-23

Writing Assignments:

Choice:

1. Halloween theme: A scene with fear in it. This could be physical danger for the main character or fear of going onstage or even a humorous reaction to the Halloween parade. Any version.

2. The frontispiece exercise from today or the change of tense.

2. Substitute!

Reading Assignments:

- If you didn't read the ones on tense, consider reading them:

MasterClass on Writing a novel in the Present Tense

Article on Pros and Cons of Present Tense

- Check out Jane Friedman on Getting Published.

- OPTIONAL: In Ten Strategies, read in Strategies 7 and 8 comparing what film and novels do best.

Presentation Schedule

Session 8

11-1-23Film and Novels:

What We Can Learn from Each Other

Panoramic view of Los Angeles;scene from The Godfather; Mad Max: Fury Road; North by Northwest;

Homework Due 11-1-23

Writing Assignments:

Choices:

1. Halloween theme: A scene with fear in it. This could be physical danger for the main character or fear of going on stage or even a humorous reaction to the Halloween parade.

2. The frontispiece exercise: This is a structure exercise, about finding the center, the most crucial turn of the story--like the climax of a a plot and analogous to (but not the same as) "the main idea" or "what it's about." A novel may, of course, have several of these, especially if it has several strands of story. Pretend your novel is being published in the 19th century, when illustrations were common in good editions of novels--lovely line drawings. The novel will have a frontispiece, an illustration of an important moment in the novel that attracts a potential reader First, Describe the black-and-white illustration as it would appear in the front of the novel. Then, Write the scene.

3. Substitute!

Reading Assignments:

- If you didn't read the ones on tense, consider reading them now:

MasterClass on Writing a novel in the Present Tense

Article on Pros and Cons of Present Tense

- Check out Jane Friedman on Getting Published.

- OPTIONAL: In Ten Strategies, read in Strategies 7 and 8 comparing what film and novels do best.

Presentation/Critique Schedule

Weekly topics

I. Business

Don't forget NaNoWriMo

Next week: Three Presenters--Susan, Kristen, Kea. Pieces should arrive by Sunday night.

For those interested in more classes and workshops, summer conferences etc., take a look at my Resources for Writers page. Also, consider subscribing or buying a hard copy of Poets & Writers. Lists of conferences, services, contests, and more. Good stuff, highly recommented. Online, Newpages.com has a lot of resources.

Novel writing, by the way, may be taken repeatedly.

Each presenter gets @ 25 minutes when we have three people.

Other business, questions?

II. Write

The Silver Screen Exercise. We mentioned this last session.

III Share.

IV. Presenter One: Linda Atlas

V. Presenter Two: Beatriz Fontes

VI. Break

VII. Mini Lecture on Film and Novels

1. Techniques film and novels learned from each other:

Film and novels have different strengths, but constantly learn from each other. The earliest movies borrowed things like the panoramic or establishing shot from novels and close-up as well. Take a look at the following lines from near the beginning of Charles Dickens' Great Expectation.The narrator is Pip, who speaks of himself in the third-person. You can easily imagine the camera panning around the countryside showing cattle, the river, and so forth, and then there is a sudden transition to a close-up.

Ours was the marsh country, down by the river, within, as the river wound, twenty miles of the sea....The dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dykes and mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it, was the marshes; and that low leaden line beyond was the river; and that distant savage lair from which the wind was rushing, was the sea; and that small bundle of shivers growing afraid of it all and beginning to cry, was Pip.

"Hold your noise!" cried a terrible voice, as a man started up from among the graves at the side of the church porch. "Keep still, you little devil, or I'll cut your throat!"

A fearful man, all in coarse grey, with a great iron on his leg. A man with no hat, and with broken shoes, and with an old rag tied round his head. A man who had been soaked in water and smothered in mud, and lamed by stones, and cut by flints and stung by nettles, and torn by briars; who limped and shivered and glared and growled; and whose teeth chattered in his head as he seized me by the chin.

Do you think this old b&w still from Great Expectations works as well as Dickens description of the moment from Pip's point of view?

So movies learned from novels, but the beautiful film panoramas have influenced novelists. Take a look at this passage from Cormac McCarthy's splendid Blood Meridian:

In the evening they came out upon a mesa that overlooked all the country to the north. The sun to the west lay in a holocaust where there rose a steady column of small desert bats and to the north along the trembling perimeter of the world dust was blowing down the void like the smoke of distant armies. The crumpled butcherpaper mountains lay in sharp shadowfold under the long blue dusk and in the middle distance the glazed bed of a dry lake lay shimmering like the mare imbrium and herds of deer were moving north in the last of the twilight, harried over the plain by wolves who were themselves the color of the desert floor.

2. Another important thing novels have picked up from film is the jump cut.

In film, the camera stops, then starts again, possibly with an establishing long shot, and we're are later or elsewhere.