Spring 2022

Novel Writing Workshop -- WRIT1-CE9357-001

By Zoom

Wednesdays February 23, 2022 - May 4, 2022

No Class April 20, 20226:30 p.m. to 8:50 p.m.

Instructor: Meredith Sue Willis

E-mail: MeredithSueWillis@gmail.com

Meredith Sue Willis Home Syllabus Various NYU policies Individual Presentation Dates

updated 5-4-22

Good Luck to All on Your Novels!

This page will stay online till June 15, 2022

New to read:

Philip Klay on how to write about war.

Jordan Kisner inThe Atlantic on failing to cross cultural divides in fiction (a review of Geraldine Brooks's Horse).

Something to think about: Using the latest technology in your novel

How a story was submitted forty times over ten years, and finally....

Current Week

Presentation Schedule

Do you know these living novelists?

How about these late and great?

See below for names

Please note that this site changes often. It will be

updated at least once a week, so check back often.

An outline of the class will be available by noon of class day.

For an overview of weekly topics, click here.

Class Members Writing & More Available Online:

Learn about class member Jo Fekete.

Poem published by Jo in The Stillwater Review Vol. 10 2020.

Jody Girgenti on IMDB. Also,see this interview about how My Friend Dahmer was made.

Alison Hubbard: "Wildflowers"

Suzanne Martinez website: links to her stories

MSW grandmother stories online:

Tentative Outline of Weekly Topics

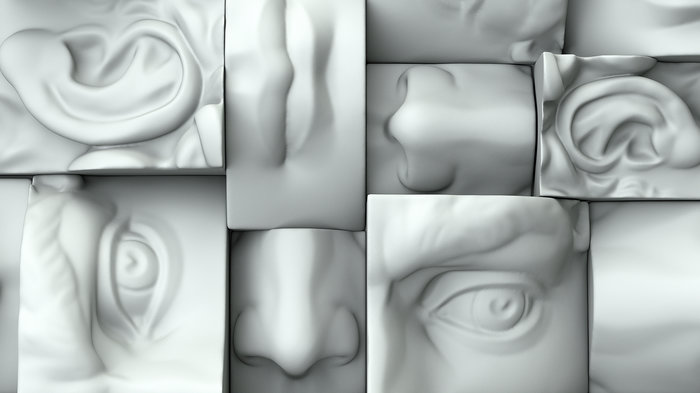

1. 2-23-22 Leading with the senses: Importance of Sense Details to Fiction Writing: for writer and reader. Places, People.

2. 3-2-22 Point of View

Presentation of Student Work for Critique3. 3-9-22 Dialogue and Scene I: Writing Vivid Dialogue

Presentation of Student Work for Critique

4. 3-16-22 Dialogue and Scene II: Scene & Dialogue II: Group Scenes; Dramatize versus Summarize; Monologue (inner speech);

P resentation of Student Work for Critrique5. 3-23-22 Structure I: Conflict and Story Arc (compare to Plot). Logistics.

Presentation of Student Work for Critrique6. 3-30-22 Structure II: When, How, & If to Outline

Presentation of Student Work for Critrique7: 4-6-22 Film Techniques for Novelists & Things Novels Do Better than Movies

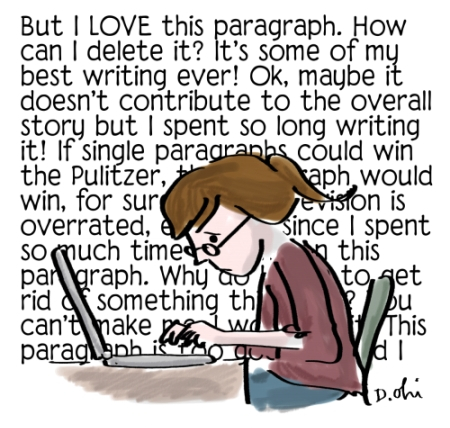

Presentation of Student Work for Critrique. Physical Action. Developing Character; Minor Characters8. 4-13-22 Revision I: Revising Novels

Presentation of Student Work for Critrique4-20-22 No Class

9. 4-27-22 Marketing and Other What Next? Issues: What do you do with your novel once you've finished writing it?

Presentation of Student Work for Critrique10. 5-4-22 Revision II: Diction and Fine Tuning (Final Session)

Presentation of Student Work for Critrique

Things to Read (Optional)

Do you need ideas for starting your novel? Check out MSW's article online from The Writer: "How to Get a Novel Started."

A close reading of a well-made first paragraph (Emily Temple on True Grit)

Authorspublish Newsletter Free and useful

Do-It-Yourself MFA

Deep Point of View (from Masterclass.com

Samples of Editing in a piece by Danny Williams called "Real Life Adventures in Editing"

Power Point Primer on book reviewing--a good primer.

Just for fun: Fifty-very-bad-book-covers-for-literary-classics/An article in Jane Friedman's blog about use of various types of third person in fiction.

Article in A Journal of Practical Writing: "Cultural Appropriation in Creative Writing.

On using the present tense: http://www.meredithsuewillis.com/materials.html#presenttense.

Spring 2022

Novel Writing Workshop -- WRIT1-CE9357-001

By Zoom

Wednesdays February 23, 2022 - April 27, 2022

6:30 p.m. to 8:50 p.m.

Instructor: Meredith Sue Willis

E-mail: MeredithSueWillis@gmail.comMeredith Sue Willis Home Syllabus

Various NYU policies Individual Presentation Dates for Critiquing

Schedule of Classes

Current Week

Presentation/Critique ScheduleOptional Text for this Course: Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel by MSW

(Available NYU Bookstore, from the publisher, and from

all the usual online suspects including Bookshop.org.)

Session 1

2-23-22

Class Structure, Importance of Concrete Language

& How to Talk about Novels

Business

A lot of business today--apologies to those

who have taken this course before.

For NYU Rules 'n Regs Here

This class welcomes beginning novelists as well as writers who are well-underway on a novel and need further discussion and stimulation to continue or restart. We will cover a lot of basics fast, beginning with a survey of common terms for discussing novels and a look at novel structure in general. If you feel you need more of the basic terminology and ideas, please take a look at the teacher's book, Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel.

For those with longer or revised manuscripts, this course may be repeated.

This syllabus will be updated regularly online, so please check this web page at least once a week. Access to the website is also available from MSW's home page. Look at the top left.

All writing and presentation selections should be from the novel you're working on.

During the course, you may bring a total of up-to 50 manuscript pages for critique (some of these pages will be for the whole group, some only for the teacher). Assignments are optional and go only to MSW. Anything you turn in to MSW, however, counts towards the total of 50 pages to be reviewed during the semester.

Please be prepared to discuss the work of classmates when they present.

Presentation pieces go to the instructor and whole class. Homework assignments go only to the instructor.

You will receive a grade for this course unless you request a NonEvaluative mark. For the Non-Evaluative, please see the attached form. A copy of this request must be filed with the department. Send it by e-mail to .

No letter grade will be given below a B. To earn a B, you must attend regularly, complete 50 pages to the professor's satisfaction plus present work for critiquing by the class at least once. To earn an A, you must attend regularly, complete the 50 pages, present work for critiquing by the class at least twice, show evidence of having done any outside reading, plus participate in class discussions.

It should be noted that all NYU policies on academic integrity, i.e., plagiarism, are fully in effect in this course. For various NYU policies, click here.

Disclaimer: Syllabus is subject to change due to current events, guest speaker schedule changes, and/or level and interests of students.

No-evaluative Grade Information: if you don't want a grade, you must follow these instructions.

Reading Assignments Due 2-23-22:.

In Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel, read "Strategy 1: Separate Process and Product" or this excerpt from the book :Click on the "Read an Excerpt" at this link link. (Optional)

Getting the right spacing between paragraphs in Word

A piece from The Guardian on adverbs

Look over conventional editorial marks.

Writing Assignment Due 2-23-22:

-

A one page or less summary or outline of your novel

-

The first page--a sample of your writing.

I. Structure of the course & more business. Things we'll do during class-time:

-

Send MSW by chat or e-mail: your snail mail address; names you want to be called; corrections to e-mail, etc.

-

May I share e-mail list with other members of the class?

-

Readings for homework (some optional, many online)

-

Class members passages for presentation/critique

-

Mini-lectures (MSW talks)

-

Discussion (as much as possible)

-

In-class writing

-

For general topics by week, click here.

II. Repeat: Material you send in for responses ("Homework"). There are three kinds:

1. The weekly assignments should be @ 2-3 pages long. They are not required, but are a good way to move your novel forward. These pages are sent only to MSW. They are due on the day of class (thus, the "Writing Assignments due" for Session 2 are due any time March 2, 2022 (before or after class). If they don't arrive that day, there is no guarantee they will be returned by the next session. You may send longer passages, but please let MSW know your plan so she doesn't get swamped at the end!

2. Substitutions: especially for people taking this class again, or who have an in-process novel--you may send any pages you want to the instructor for feedback. These pages are sent only to MSW. They are due on the day of class (thus, substitute pages for Session 2 are due some time on March 3, 2021. If they don't arrive that day, there is no guarantee they will be returned by the next session.

3. Presentation pieces for critiquing (as short as you'd like, but no more than 10 pp. double spaced, 1 inch margins, roughly comparable to 12 pt. New Times Roman Type face) are sent to the entire class. These presentation pieces are to to arrive in people's e-mail in boxes by Sunday night before the presentation.

VIP: the total pages you may turn in to MSW cannot be more than 50 pp. This includes worked to be critiqued by the whole class and assignments sent only to MSW.

When there is work to critique, be prepared to discuss it by the time the class member presents

III. Class guidelines with Zoom

-- Please have your camera turned on.

-- Put yourself on mute when you're not talking so we don't have to hear your puppy, your partner in the kitchen, etc. The mute button is at lower left of the Zoom screen.

-- Raise your physical hand if you want to speak.

-- Speak one at a time--in practice, this means waiting for the instructor to call on you.

-- Try to be succinct.

-- Listen and respect each other's ideas. We are writing different kinds of novels, and if possible, try to make suggestions based on helping each other write the best novel of the type we are writing.

-- Use the chat function for procedural notes to the instructor ( you got a text from a classmate who can't get in; the name of a book you couldn't think of and wanted to share....)

-- Apologies in advance: I may have to interrupt/cut you off. We try for equal time for each person, and I also have an ambitious plan for what to cover.

-- Technical note for Mac Users on Zoom: To view screen share in Zoom at full screen, see the top drop down menu and set to "100%"

IV. Go round of introductions-- name, a line or two of background (try not to apologize that you have not written much yet!)

V. Senses in writing

We do Macro (big pictrure stuff) and Micro which means here detail, especially concrete detail.

1. Everything is built with concrete observation and sense details.

2. All senses (not just sight) come into play.

3. Here's an example from fiction-- a story called "Consultation" by Ariel Dorfman

What sense or senses are missing?

4. Here's one I like that describes a person.

5. Example from one of the first pages turned in today.

VI. WRITE

Describe a character in your novel using all (or as many as possible) of your senses.

VII. Share some.

VIII. How do we talk about ("critique") novels

What do you find useful? Not useful?

For me, it's always How to make this novel (scene, passage) the best it can be at what it wants to be.

Here's a sheet to help people critique your passage. You might want to print out--use as a reference.

IX. BREAK

X. Common Vocabulary

Common vocabulary--Process versus product, pacing, when to dramatize, when to elide. Essential importance of Point of View in all fiction. Scene and summary. What is Scene? Why is it important? The building block of novels. But at the heart is concrete details.Process versus product, pacing, when to dramatize, when to elide.

See Terms we'll be using this semester.

XI. SCHEDULE PRESENTATIONS FOR CRITIQUE.

This is for many people the most important thing. PLEASE GET WORK TO WHOLE CLASS BY SUNDAY NIGHT. Also, part of your job is to read and respond. Ask questions to direct us in what you need. (close line editing? Or is this rough and you mostly want general reactions?

Consider using the critiquing sheet mentioned above (or your own variation on it) for responses.

XII. Write a Macro Exercise

Macro exercise about the novel you are planning/engaged in. Your novel--write about it, talk about it.

Answer these questions about your novel using this list of Types of Novels if you need it.

XIII. Homework and readings for next week

Writing assignments:

1. E-mail all class members with a one page summary or outline of the novel you will be working on this term.

2. An important room or other place in your novel (indoors or out).

Focus on concrete language and senses, and try to make it psychologically accurate--that is, not every possible detail, but maybe an over view first, or maybe a person entering the space, noticing first the temperature, then one large object, etc.

Reading Assignments:

Ten Strategies, "Strategy 4: Find Where You Stand as You Tell Your Story." (optional)

Point of view chart online plus skim a few of these examples of various points of view.

Also, if you haven't read it before, check out the Kilted Warrior example of amateurish (IMHO) omniscient POV.

Session 2

3-2-22

Point of View:

Where I Stand as I Tell the Story

Writing assignments due tonight 3-2-22:

1. E-mail all class members with a one page summary or outline of the novel you will be working on this term plus the first page or other writing sample..

2. Describe an important room or other place in your novel (indoors or out). Focus on concrete language and senses, and try to make it psychologically accurate--that is, not every possible detail, but maybe an over view first, or maybe a person entering the space, noticing first the temperature, then one large object, etc.

Reading Assignments:

Ten Strategies, "Strategy 4: Find Where You Stand as You Tell Your Story." (optional)

Point of view chart online plus skim a few of these examples of various points of view. Also,look at the Opening of Great Expectations and some Point of View Problems .

Also, if you haven't read it before, check out this example of amateurish omniscient POV ("The Kilted Warrior".

I. Business

-- From last week: Here is the page of "Quotidian" scenes and Objects

Reminders:

It's your choice to do the assignments or substitute, but everything should be from your novel. The total number of pages you may turn in for response from the instructor is 50 (that includes pieces presented to the whole group and homework for the instructor alone).

Reminder about what is due when:

1. The weekly assignments should be @ 2-3 pages long. They are not required, but are a good way to move your novel forward. These pages are sent only to MSW. They are due on the day of class.

2. Substitutions: you may always substitute pages from you novel of your choice.

3. Presentation pieces for critiquing are to to arrive in people's e-mail in boxes by Sunday night before the presentation at the very latest.

Questions:

Who wants no grade? You will receive a grade for this course unless you request a NonEvaluative mark. For the Non-Evaluative, please see the attached form. A copy of this request must be filed with the department. Send it by e-mail to .

2 or 3 presentations: sign up sooner rather than latger. A couple of people haven't signed up yet--get your second one too. See Schedule below.

Please send Snail mail addresses to MSW.

II. WRITE:

I promised we'd be going macro and micro-- here's a Macro exercise about the novel you are planning/engaged in.

Answer these questions about your novel using this list of Types of Novels if you need it.

III Discuss the exercise (briefly)

IV. A Short Go-Round....

... on how you responded to the presenters' writing. Jo Fekete wrote one page notes. I did my usual hand-written respond-as-I go, plus holistic note at the end. Others?

V. Presenter One: (A lot of the "instruction" in this class comes as we go over people's work.)

Jody Girgenti; Alison Hubbard; Suzanne Martinez

VI. Presenter Two:

Jody Girgenti; Alison Hubbard; Suzanne Martinez

VII. BREAK

VIII. POINT OF VIEW

Point of View

Essential importance of Point of View in all fiction. Voice-- for the reader, but also the writer. How we go into our story.

Point of View chart to establish the vocabulary.

Point of view samples

An article on various 3rd persons

lllusion of how the story is told

Time frame/span: some very clear. It's an important thing to work out: the present time of the story. That is, the farthest forward time as we tell it, irrespective of flashbacks, etc. Part of structure. The present time of James Joyce's novelistic long story "The Dead" is the 5 or 6 hours of a party plus going to a hotel to sleep.

A Point of view problem example: "The Thriller Bar Scene."

IX. Presenter Three:

Jody Girgenti; Alison Hubbard; Suzanne Martinez

X. Write

Put a war in your novel....

For next week:

Writing Assignment due:

A crucial dramatized scene in your novel from somewhere toward the middle; OR put a war in your novel!

Reading/Listening Assignments:

Short reading: : Dialogue Tags ; Types of Discourse; and " Dialogue: The Spine of Fiction." (article by MSW about dialogue online).

Ten Strategies, "Strategy 5: Master Dialogue and Scene" (optional)

An eleven minuted recorded lecture by me on Scene (optional)

Session 3.

3-9-22

Scene & Dialogue I:

Writing Vivid DialoguePresentation Schedule

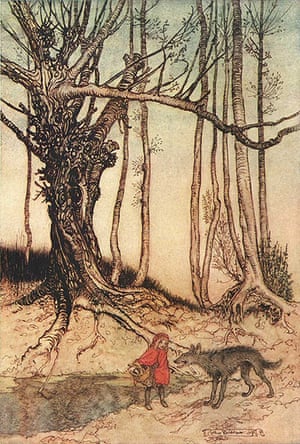

Scene from movie of Night of the Hunter (book by Davis Grubb); 'Little Red Riding Hood; illustration of end of George Eliot's The Mill on the River Floss;

Writing Assignment due:

Choose one: A crucial dramatized scene in your novel from somewhere toward the middle;

OR put a war in your novel!

Reading/Listening Assignments:

-

Short reading: : Dialogue Tags ; Types of Discourse; and " Dialogue: The Spine of Fiction." (article by MSW about dialogue online).

-

Ten Strategies, "Strategy 5: Master Dialogue and Scene" (optional)

-

An eleven minute recorded lecture by me on Scene (optional)

Class Members Writing & More Available Online:

Learn about class member Jo Fekete.

Jody Girgenti on IMDB. Also,see this interview about how My Friend Dahmer was made.

Alison Hubbard: "Wildflowers"

Suzanne Martinez website: links to her stories

MSW grandmother stories online:

I. Business

Any confusion about what teacher will read? 50 pp includes everything, so if you turn in 20 pages to class for critique, I'll read up 30 pages more including home works. You don't have to turn in 50 pp.

The weekly assignments should be @ 2-3 pages long. They are not required, but are a good way to move your novel forward. These pages are sent only to MSW. They are due on the day of class.

Substitutions: you may always substitute pages from your novel.

Some people haven't signed up to present yet.

Presentation pieces for critiquing are to arrive in people's e-mail in boxes by Sunday night before the presentation at the very latest.

Conventional formatting and spacing in Word for pages– narrative paragraphing, not block paragraphs. See link...)

Grounding This is what makes the world of our plots and emotions real: easiest if readers know the world, of course, but don't assume too much. If the story is set in 1990, are there smart phones? For fantasy and science fiction, be very careful to build a world. Can you (in past, in fantasy world) even use imagery that stays in place? If story takes place in a semi-medieval world, would you say he looks like an anime character?

II. Go-round Discussion: Why I am taking this course? What do I need from this course?

III. WRITE:

Put some feet in your novel. Main character studying someone else's (describing); getting a pedicure; feeling of feet during a run or with uncomfortable shoes. Or anything else with feet.

IV. Sample:

From a novel called Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard by Kiran Desai:

"Sampath was transfixed. Miss Jyotsna kicked her feet up in the air. (What red toenails! Jewel-like, beetle-like, beautiful red toenails!) His ears felt as if they'd been dusted with a light coating of paprika."

V. Share?

VI. Presenter:

Jo Fekete

VII. Dialogue

We are talking today about how dialogue works. We all know what it is. BUT for novel writing:

Dialogue is where the drama is-- conflict, confrontation, love!

Closest thing to "real" as anything in prose narrative. Real time, real words BUT in spite of that, we're after the illusion. Transcription of a real dialogue too long and boring. Our job is to create the illusion of peop;lespeaking.

Types of Discourse

Dialogue Tags

Dialect Samples and two more examples of dialect-- Mark Twain and Jeanette Winterson

Dialect Issues: Ed Davis's article in the Writers Digest's Blog about writing dialect.

Dialogue in Two Languages

VIII. Break

IX. More Dialogue

If it isn't natural to you, a good technique to try is to write down JUST THE WORDS SAID, then go back and add:

setting

descriptions

tags

modifers to the tags

some inner monologue

And then go back a third time and cut away everything that isn't interesting!

X. EXAMPLE

Yonnondio

XI. WRITE

See if you can put this in your novel.

Hi.

Hi.

I guess this is it.

I guess it is.

Then add the parts we've been talking about.

XII. IF TIME:

A Macro Writing: Name (or make up) 5 of the most important dialogues in your novel.

XIII. Assignments for Next week

Writing Assignment due:

Either: Finish the dialogue from Hi-Hi-I guess this is is-I guess it is; or write a dialogue with a conflict in it

Reading assignments due:

Night of the Hunter scene; Yonnondio; Huck Finn and Winterson; A Man Told Me by Grace Paley: A dialogue within a monologue; and The Death of Mrs. Ramsay from To the Lighthouse.

Scene and summary. What is Scene? Why is it important? The building block of novels. Some ways of telling a story– central one is scene. Please be sure and read the things online about scene, but in a nutshell, it's the unit of the novel–not the only thing, and some novels it isn't even the main thing, but always crucial for drama, for the reader visualizing the action.

Optional: 10 Tips for Strong Scenes (from Masterclass.com, and, if you didn't read it yet: Ten Strategies, "Strategy 5: Master Dialogue and Scene" (optional); An eleven minute recorded lecture by me on Scene (optional). To view it, you'll have to download it to your computer.

Presentation Schedule

Session 4.

3-16-22

Scene & Dialogue II:

Group Scenes; Dramatize versus Summarize;

Monologue (inner speech)

Writing Assignment due:

Either Finish the dialogue from Hi-Hi-I guess this is is-I guess it is; or write a dialogue with a conflict in it

Reading assignments due:

Night of the Hunter scene; Yonnondio; A Man Told Me by Grace Paley; and The Death of Mrs. Ramsay from To the Lighthouse.

Optional Reading: 10 Tips for Strong Scenes (from Masterclass.com, and, if you didn't read it yet: Ten Strategies, "Strategy 5: Master Dialogue and Scene" (optional)

I. Business

Any questions about pages to turn in, schedule, etc?. Can you read my scanned homework and presentation responses?

Everyone happy with presentation schedule?

How are the scans of my handwritten notes?

MSW's Pet Peeve department:

Smirk-- Smile in an irritatingly smug, conceited, silly, or evil way. “So you love me, do you?” said Tom with a smirk. Is he serious?

II. First Presenter: Isabella, Laurie-Maude, Alison

III. Write:

Put something green in your novel.

IV. Second Presenter: Isabella, Laurie-Maude, Alison

V. BREAK

VI. Scene

A.

(With apologies to those who took my one-day workshop on scene in January)

Scene and summary. What is Scene? Why is it important? The building block of novels. Some ways of telling a story– central one is scene. It's the unit of the novel–not the only thing, and in some novels it isn't even the main thing, but always crucial for drama-- for the reader visualizing the action.

Here are two brief, well-realized scenes:

And here, a great summary-- not a scene:

The Death of Mrs. Ramsay from To the Lighthouse.

B.

Strategies for group and crowd scenes

Here are a couple of practical strategies for dealing with logistics and large groups. Not tricks-- all prose narrative, after all, is an illusion of reality-- but as you revise, you can try these things to make the storytelling run more smoothly.

Only identify two or three individuals in a scene. Say "The twenty two members of the Ridgewood Bobcats walked into the dressing room with long faces," and then give quoted speeches only to Rob, Andre, and the Coach. The other Bobcats can mutter as a group, or lower their heads in shame, but they remain a mass, part of the scene setting.

As above. only give proper names to the most important characters in a group scene. (Be sure you really need the names. Proper names call attention to themselves, slow down the flow of the story.)

Clarify the logistics and physical action by giving a firm point of view. Imagine a fixed camera or a character in a chair in the northeast corner next to to the white board. Write only what is seen from that point of view. This will help keep the reader oriented. Even if you have a multiple viewpoint story, write your action from one point of view.

Conflate. If you are writing fiction based on, say, your own large family, conflate two annoying little brothers into one. It strays from the facts, but allows the creation of one full character and eases your logistical problems.

C.

A little on interior/internal monologue

Monologue and minor characters

So-called "inner dialogue" or monologue (from Editor's Blog). Talks about punctuating it, too.

Joey looked at the two women posing as his long-lost cousins. Stupid ignorant fool. Should have known better than to hope.

Joey looked at the two women posing as his long-lost cousins. Stupid ignorant fool, he thought to himself. Should have known better than to hope...

Joey looked at the two women posing as his long-lost cousins. Stupid ignorant fool. Should have known better than to hope...

A Man Told Me by Grace Paley: A dialogue within a monologue

VII. Third Presenter: Alison

VIII. Assignments For next week:

Writing Assignment due:

Choice: (1) A scene with a group or crowd; or, (2) expand the "green" in-class writing.

Reading Assignments:

So-called "inner dialogue" or monologue (from Editor's Blog). Talks about punctuating it, too.

If we didn't get to it in class, read this very short story: "A Man Told Me" by Grace Paley:

(Optional) In Ten Strategies read "Strategy 6: Structuring Your Novel," pages 77-96

(Optional) If anyone is still looking for it, try this for the eleven minute recorded lecture by me on Scene. To view it, you'll have to download it to your computer.

Presentation Schedule

Session 5.

3-23-22

Structure I:

Plot, Story, Architectonics

Writing Assignment due:

Choice:

(1) A scene with a group or crowd; or,

(2) expand the "put green in your novel" writing.

Reading Assignments:

So-called "inner dialogue" or monologue (from Editor's Blog). Talks about punctuating it, too.

If we didn't get to it in class, read this very short story: "A Man Told Me" by Grace Paley:

(Optional) In Ten Strategies read "Strategy 6: Structuring Your Novel," pages 77-96

Just for fun: Fifty-very-bad-book-covers-for-literary-classics

I. Business

Next week, we'll try NYU's Zoom. Watch for an e-mail explaining what to do to get there--and what to do if they cut us off.

Watch for a link to a short survey/evaluation

Tentative Outline of Upcoming Class topics

Homonyms/homophones (homonym: "dear, dear." Homophone: "dear, deer").

Try to correct them in your writing. Spell check won't catch 'em.

1. There, Their, and They're

2. Your and You're

3. Two, Too, and To

4. It's and Its

5. Peak, Peek, Pique, and Peke

6. Who's and Whose

II. Go-Round Discussion on How Your Novel Is Going? Time Management problems-suggestions?

What's going well?

What are your "challenges?"

III. Presenter One: Suzanne

IV. WRITE

A timed free write on your novel. Think of a single object to stand for the novel, and then write wherever your mind goes, about the novel, for five minutes.

V. BREAK

VI. Presenter Two: Jody

VII. Some Materials and Things to Think About with Structure

Big Bins and Other Ways to Picture how your story is organized. I sometimes call these biggest, loosest ways of seeing, collecting your material "architectonic," which is a fancy way of saying architecture. It's about design and how to support your ideas. Try some large containers: Part I--1908; Part II World War Two; Part III--the Sixties; Part IV-- 2000; Part V--the Present.

More big, simple, highly useful ways to collect and contain your material: Places (New York, Rio, New York again); Characters (each section has a pov character for say 50 pages); a chronological life story; Life story of coming to adulthood (bildunsroman); story of a summer; story of a friendship or love affair. Various generally linear, chronological story lines.

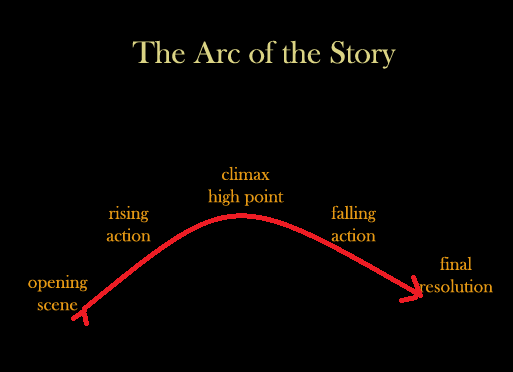

Freitag's pyramid (probably too simple for a novel)-- but it can be helpful to think about how your story moves.

Generally, to oversimplify greatly, stories are simple. often linear (or linear with flashbacks or linear after we find out the ending) and everyone uses the same ones: a life story, a love story, a quest, Jane Austen's marriages to tie up loose ends, etc. Plot is more knotted up, more clever. The story ends with the lovers together; the plot is full of meet-cute, clever misunderstandings, tensions, etc.. Many novels have both: an underlying story, and a superficial plot for fun, for excitement, to draw the reader on: Whodunit overlies a coming to maturity of the sleuth.

Classic novel shapes; question to answer etc. a violent act and consequences; start and the end, and the novel is how we got there, etc. – from problem to solution – from mystery to solution – from conflict to peace – from danger to safety – from confusion to order – from dilemma to decision – from ignorance to knowledge– from questions to answers.

One I particularly like, especially for early drafting, is the : Archipelago structure (scenes)

Other Common patterns that can be useful: Hero's Journey and Multi-plot novels.

VIII. WRITE or THINK

This is a structure exercise, about finding the center, the most crucial turn of the story--like the climax of a a plot and analogous to (but not the same as) "the main idea" or "what it's about." A novel may, of course, have several of these, especially if it has several strands of story. Pretend your novel is being published in the 19th century, when illustrations were common in good editions of novels--lovely line drawings. The novel will have a frontispiece, an illustration of an important moment in the novel that attracts a potential reader

Describe the black-and-white illustration.

(At another time, write the scene.)

IX. Homework for next week

Writing Assignment

You may always substitute pages of your own choice.

This is a structure exercise, about finding the center, the most crucial turn of the story--like the climax of a a plot and analogous to (but not the same as) "the main idea" or "what it's about." A novel may, of course, have several of these, especially if it has several strands of story.

Pretend your novel is being published in the 19th century, when illustrations were common in good editions of novels--lovely line drawings. The novel will have a frontispiece, an illustration of an important moment in the novel that attracts a potential reader

First, Describe the black-and-white illustration as it would appear in the front of the novel

Then, Write the scene.

Reading Assignments :

Stakes Method of Outlining

Read Outlining from Ten Strategies (selections from Chapter 6)

OPTIONAL: In Ten Strategies, read in "Strategy 6: Structure Your Novel." page 96 - 102, "The Best Time to Start Outlining."

Summary of how to structure Multi-plot novels.

Presentation Schedule

Session 6. 3-30-22

Structuring Your Novel II:

Uses of Outlining--Time and Tense

An archipelago--scenes from your novel?

Lengths of novels and novellas and genre novels (this is from a blog/business called Reedsy).

Homework due this week:

Writing Assignment

You may always substitute pages of your own choice.

This is a structure exercise, about finding the center, the most crucial turn of the story--like the climax of a a plot and analogous to (but not the same as) "the main idea" or "what it's about." A novel may, of course, have several of these, especially if it has several strands of story.

Pretend your novel is being published in the 19th century, when illustrations were common in good editions of novels--lovely line drawings. The novel will have a frontispiece, an illustration of an important moment in the novel that attracts a potential reader

First, Describe the black-and-white illustration as it would appear in the front of the novel

Then, Write the scene.

Reading Assignments :

Stakes Method of Outlining

Read Outlining from Ten Strategies (selections from Chapter 6)

OPTIONAL: In Ten Strategies, read in "Strategy 6: Structure Your Novel." page 96 - 102, "The Best Time to Start Outlining."

Sample outlines:

I. Business

Don't forget to fill out the Zoom survey--only a couple of people have responded so far.

Presentation pieces! Please don't forget! The limit is 10 pages, double spaced, 12 pt. font, one inch margins all around. Also, you are expected to read and give at least a short response to all work. See the full statement on this here.

Lengths of novels and novellas and genre novels (this is from a blog/business called Reedsy).

Isabella's structuring "trick."

DID WE GO OVER THIS LAST WEEK?

Homonyms/homophones (homonym: "dear, dear." Homophone: "dear, deer").Try to correct them in your writing. Spell check won't catch 'em.

1. There, Their, and They're

2. Your and You're

3. Two, Too, and To

4. It's and Its

5. Peak, Peek, Pique, and Peke

6. Who's and Whose

II. Presenter One: Melissa

III. Presenter Two: Isabella

IV. Mini-Lecture on Outlining:

I am personally partial to:

-- The Archipelago method

-- The Hypothetical Outline

You make up a hypothetical or test plot. Write down a beginning, middle, and end. Write as if that made-up plot were your plot, but be ready at any moment to change it. This gives you a structure to work with (especially an end point) but gives preference to changes that your imagination might come up with.

-- The "Running Outline," which is a daily record of progress and changes. Rrunning outline

But there are lots more:– The chronological outline

–Beat Sheet.

– Isabella Barrengos's Novel Organizing/Structuring "Trick"

Reformat your novel in your printing settings -- select the options to print two pages per sheet and to print horizontally (make sure to number your pages)

Lay out every page on the floor (preferably somewhere with a lot of space and no open windows/air vents otherwise your pages will move around!)

Gather different color sticky notes and decide what themes, sections, structures you'd like to study in your revision:

– Major plot points

– Major turning points for characters

– Flashbacks

– Time jumps

– POV changes

Assign a color to each thing you'll be highlighting and put the sticky note on the pages where you see this pop up Step back and visualize!

You can also write directly on the pages, highlight large swathes, etc. Do whatever helps you see the overall arc of the story, where there might be lulls, where things might be happening too early or too late etc.

– Snow flake structure

Based around the idea that a writer begins with a simple idea or brief situation and over time, develops and adds complexity. Can't argue with that, although it gets a little detailed and prescriptive IMHO.

You start with a simple idea and then build on this idea until it transforms from a single sentence into a full-blown novel.

Associated with Randy Ingermanson. Here's an interview of him and summary if the snowflake structure that might interest you. Also, Ingermanson's website) . Whether or not you go for the whole thing, there are lots of good ideas.

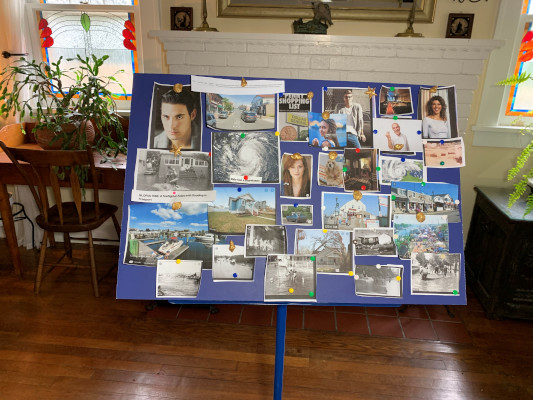

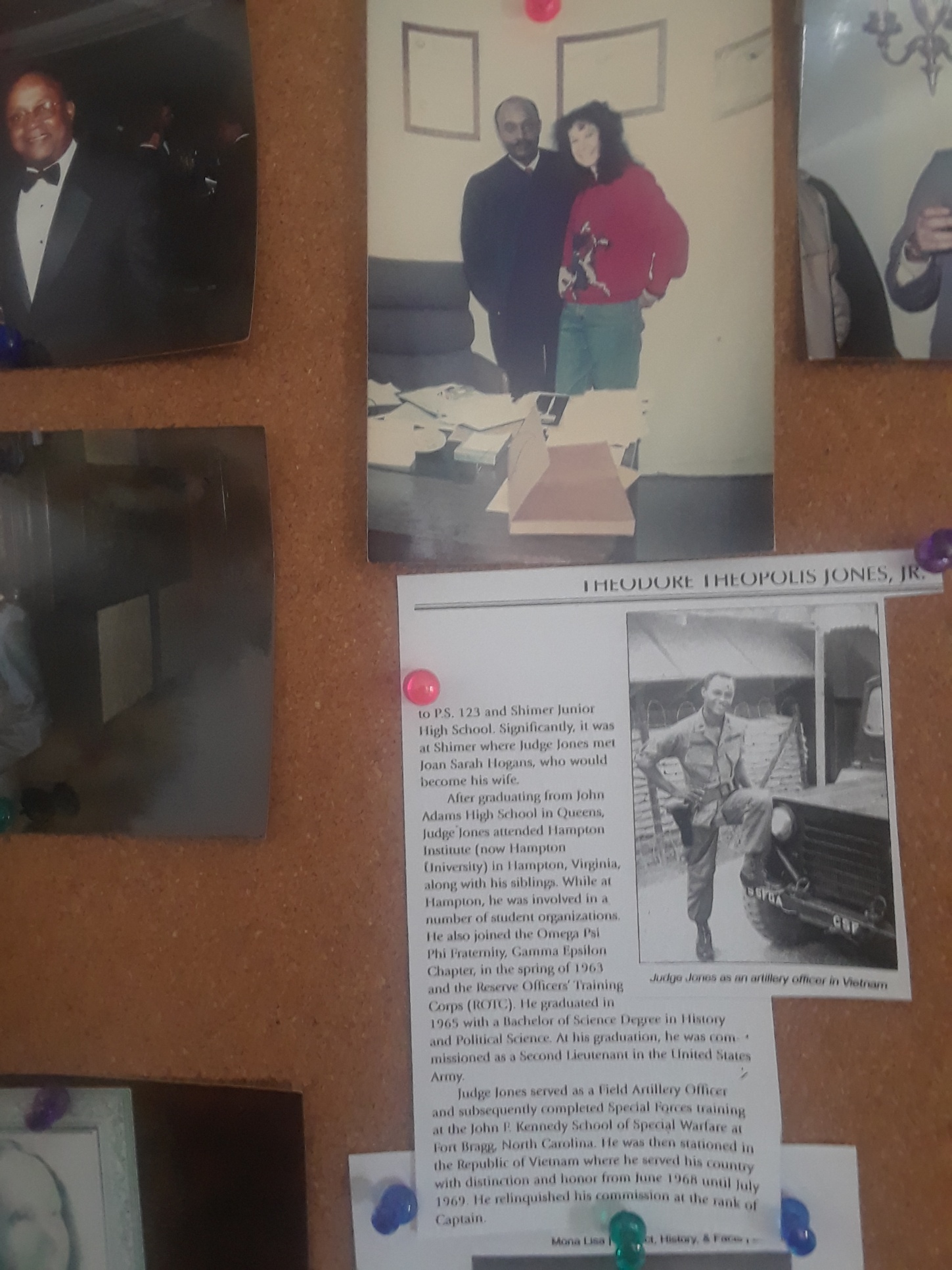

– Visual versions of your outline (also see the sample outlines below)

The "Penny Board"

Outline sample 1--a form for drafting

Outline sample 2--character diagram

Outline sample 3 a timeline outline

Outline sample 4--word drawing outline

Outline sample 5 --nonfiction book outline

Outline sample 6--running outline

Outline sample 7-- Penny Board

Note re: my sample outlines that one is a form that a writer created to help draft each chapter in the book. One is from my non-fiction book about writing a novel, which is fairly straightforward, based on teaching and workshops I've done, and much less of a struggle than my fiction outlines. . Another is from a science fiction novel of mine, and it's what I call a "running outline," that is, I update it at the end of a day's work--doing the page count, word count, date, and also making any changes (names, facts) that I came up with that day. One is a student "outline" that is really a diagram of characters that helped her in her thinking--and that's the main point of an outline: to help you visualize what you've done and to hypothesize about what you might do--and remember ideas for the future. You need to find your own best outlining method.

V. Break

VI. WRITE:

Put a "silent dialogue" in your novel. That is, have some interaction happen all in gesture: can be small or large--siblings struggling over the remote; one wants to get physical, the other resisting; etc. Go for clear, vivid description of the action.

VII. Presenter Three: Jo

VIII.

Pacing. Story Telling, and Time in novels

Flashback

the conventional story teller past, when you do a flashback, you begin in the past perfect tense (He had always gone to the Golden Dolphin after work...) and then after a couple of lines, you slip into the plain past again. This is an accepted convention of fiction writing, and it makes for vigorous story telling (He had always gone to the Golden Dolphin after work, but that day he went straight home...).

t gets tougher when you are in the present tense. The present tense is intrinsically inimical to the past: we usually write in present to keep the focus here and now. I'm not a huge fan, but more and more novelists prefer it.

Rule of thumb: if your story is in the present tense, once you've switched to the past, stay there.

But if you are writing in the past, start a flashback in past perfect and then slip back into the plain past

Present and other Tenses

A thought on revising the tense in a first person y.a. novel. I originally wrote:

I had already decided I wasn't sticking around Hawkinsville for long.

This careful use of correct tense slows things down; more importantly, it takes off stage an important decision the character is making. During revision, I changed it to

I decided I wasn't sticking around Hawkinsville for long.

This is very small, but it adds directness, which is appropriate to this character. It moves the narrative toward dramatizing rather than relating, and even moves the passage along a continuum from narrative toward scene. It isn't a scene, but moves in that direction.

1. Advantages of the Present Tense

--Immediacy- especially how it can convey change as it happens in the first person. Extends realism in the realm of time: durational realism (like old TV show "24")

--"Defamiliarization" by giving a sense of intensity and originality- less original now, of course, as many people use it.

-- Very effective in conveying disordered and disoriented mental states: dream, insanity, etc.

-- Especially valuable when it reflects a work's themes: e.g., a character who is "boxed in the present" or trying to repress the past or unable to remember the past.

2. Disadvantages

-Restricts ability to manipulate time: hard to maintain and compress time, hard to do flash forwards, flashbacks- they can destroy the illusion of presentness.

-- Harder to create characters for whom the past is important.

-- Harder to create suspense, because present tense narrators don't know what's coming.

-- Takes the story out of time. It can begin to sound like the generalized present or historical present as in, "I write in the morning" and "Shakespeare is making the point that..."

-- Tends to limit variety in narration.

-- Tends toward minimalism, and thus has less room for description.

-- Leads to including trivial things because they are realistic and "present."

-- Can feel impersonal and detached.

-- It is tricky to narrate something like a murder or rape or fight. Seems always aimed at an audience like calling a game play-by-play: "And now he's at the twenty yard line, and now..."

Some of these can be advantages, and vice versa.

IX. Next week's assignments

Writing Assignment due:

Write any outline of your novel. Use any of the methods suggested above. If possible, try two: one a standard plan for your chapters/or scenes; another a "beat sheet" or hero's journey, etc.

OR, revise and complete the silent dialogue (action) in-class assignment.

Reading Assignments:

1. Read online: Old Lady Girl novella in process ; Ellipsis Etc. ; Beat Sheet

2. (Optional) Read "Strategy Eight: Use Film Techniques" in Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel. (optional)

Presentation Schedule

Session 7: 4-6-22

What Film Can Teach Novelists--

and What Novels Can Do That Film Can't

The Godfather; North by Northwest;Mad Max: Fury Road;

Things to look at:

Published Poem by Jo Fekete

Information about the Writing Software Scrivener

It's Poetry Month! Reading Poetry is

Good for Your Writing! Get Poem-a-Day

The 99 Day Novel Course by Alison Hubbard

Here’s some info on The 99 Day Novel course I took last fall through the Iowa Summer Writing Festival online. Suzanne and I had travelled to Iowa City twice for this festival a few years back, so I was receiving regular e-mails from them. The 99 Day Novel caught my eye because I was struggling to figure out how to move forward with RIDING OUT. The e-mail came in August. There were two sessions. On the sign up day I logged in about an hour after it opened and both sessions were completely full! So this is the first thing. If you’re interested, sign up in the first minutes the class is offered. I put myself on a waiting list and as it turned out they opened up a third session.

Kelly Dwyer taught the courses. It was a boot camp for sure. There were nine three-hour sessions—sometimes two or three weeks apart, sometimes a week apart—from the “Marching Orders” class on September 2 through the last class on December 9. Mostly we used Alan Watt’s book, The 90 Day Novel, a highly organized, day by day method for writing a first draft. The first month is devoted entirely to daily writing exercises to clarify the characters, conflicts, and central theme of your novel. Watt believes in going from the general to the specific and “holding your idea loosely.” I found the exercises useful, and his words each day (ending with “Until tomorrow, Al”) very encouraging. At the end of the thirty days, as the final bit of prep before beginning to draft, Watt assigns an outline.

The second session of 99 Day was a month after the first. We were expected to have done all the prep work and exercises from the Watt and produced an outline. We were given a choice of outlines (Hero’s Journey, Save the Cat Beat Sheet, etc) but I chose the Watt. His outline is divided into three acts, each having about five points. I will be turning in an updated version of this for Meredith’s class next week, if you’re interested.

From then on, each session was an in-depth study of a particular topic, i.e. Character Arcs, Antagonists, Climax of the Novel, Ending of the Novel. We did brush over the elements of writing, POV, scenes, etc., but the thrust of the course was structural—getting the big picture and the story arc—and getting your first draft finished. Everyone was required to turn in something for each session. U of IOWA uses Canvas and we posted a few days before. The assignments were initially short, 500 words, but grew in length to 1500 words. My group was mostly from the West Coast and the Midwest. There were ten of us. Our projects ranged from a cozy mystery about a dog park killer to murders in the Eifel Tower to a gay man’s wooing of a closeted priest (mostly in a high end restaurant. . .)

How effective was this? A major discovery for me was to move my story back in time from the 1980s to the 1950s. Following Watt’s advice not to go back and read until you finish, I produced a 205 page, 61,000 word draft between Sept. 2 and early January (a few weeks after the class ended.) When I finally did read the entire thing I realized there were many holes in the draft, although I liked the way it ended. In our class, I’m trying to fill in those holes and deepen the characters, mainly Frank. A lot of what I wrote in that first draft will probably be discarded, but writing it helped me to find some clarity on my book as a whole.

The amount of work people did varied. One woman was writing a book about some friends who graduated from high school in the Midwest. She worked on an outline the entire time. At first I was skeptical about this approach, but by the end the outline was very elaborate and the character arcs were clear. There was no pressure, people worked at their own pace.

If you’re interested, the website for Iowa Summer Writing is https://iowasummerwritingfestival.org. The 99 Day Novel course has not been announced yet, but probably will be within the next few weeks when the summer festival is announced.

I hope this helps!

Best, Alison

More Vision Outlines: This one from Linda Atlas (using real life images that stimulated her novel):

Writing Assignment due 4-6-22:

Write any outline of your novel. Use any of the methods (see Linda's vision board above) as well as samples in last week's session.

If possible, try two: one a standard plan for your chapters/or scenes; another a "beat sheet" or hero's journey, etc.

OR, revise and complete the silent dialogue (action) in-class assignment.

Reading Assignments:

1. Read online: Old Lady Girl novella in process ; Ellipsis Etc. ; Beat Sheet

2. (Optional) Read "Strategy Eight: Use Film Techniques" in Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel. (optional)

I. Business for 4-6-22

Be sure and look at the "things to look at" above.

Remember: We have class next week, April 13, but No Class April 20-- everything gets moved one week forward (homework that was due April 13 is now due by April 24, etc.)

We'll continue with the NYU Zoom unless there's a problem

Laurie-Maude asked about chapter length: originally, I think, something practical for serial publication--later, a vague sense that this is wht someone would read in a sitting ("Just as soon as I finish this chapter!"). In reality? It's a convention to play with--the length of a short story? One word? I often break down long works by scene rather than chapter, so I have sections labelled 1 through, say, 34--all practical, for convenience.

Thoughts about "instruction" in a novel writing workshop--I've always chosen workshop because it's more fun for me, but also because I honestly think novel writing is a practice rather than a body of knowledge. Obviously there are things to know. My friend who read forty books on writing, then started.

Thoughts about being critiqued (my experience Monday)

II. Discussion on experience of critiquing

III. WRITE

I.

-- An action from your novel-- large "motor control" (running, fighting, lifting, climbing, dancing) using the Silver Screen technique.

IV. Presenter One: Jody Girgenti

V.Presenter Two: Laurie-Maude Chenard

VI. BREAK

VII. Presenter Three: Suzanne Martinez

VIII. Mini-Lecture on Film and Fiction: strengths, cross fertilization, etc.

This one is going to be more mini than lecture. Movies do long-shot scene setting, for example, extremely well, probably better than fiction every will. And the biggest, most obvious thing movies do best is move--they will always do straight action with great precision and aplomb. Novels with action depend more on suspense, internal reactions to what is going on, etc. Movies were also made for actorss--delicate gestures, tone, sneers.

Not as great (IMHO!) on sensuality--easily slips toward porno. And flashbacks can get real hokey real fast!

Great on small gestures, but also big danger and chases--

Especially car chases!

It's not that you can't do these things in novels--obviously you can--but we often visualize them as movies (a good writing exercise).

We learned a lot of techniques from movies, like the jump-cut. But the movies learned first from novels--Dickens and other 19th century novelists were terrific on broad-stroke scene setting (long shots).

Where novels have unique power is in internal monologue, but also in the senses other thab sight and hearing, and the manipulation of time--flashback is probably more powerful in prose than it ever will be in movies. : Ellipsis, Pause, etc.

Also, Samples of Flashback and Stream-of-Consciousness.

IX. Homework for Next Week

Take a look at this scene from Elmore Leonard's crime novel Detroit: It recreates a long panning shot with a fixed "camera" angle (point of view) as movies do, then moves in close, also like a camera shot, then flips into a little memory, so smoothly-a fictional specialty.

Writing homework: Write a scene in which your main character is standing in a high place. Have the character observe, then focus on some particular element, then go into an interior memory, speculation, even flashback stimulated by what is seen.

Or--a revision-expansion of one of the in-class writings, or anything you choose for response.

Reading Homework: Read this material on Flashback and, if you haven't yet, this on internal monologue (character thoughts), and the materials on present tenses--its pros and cons. Also, check out the samples from literature in this passage from Ten Strategies.

Also, Samples of Flashback and Stream-of-Consciousness.

(Optional) Read Strategies 7 & 8 in Ten Strategies (on what movies do best and what novels do best).

Presentation Schedule

Session 8.

4-13-22Revision One

Extras:

Tokyo has a café you can't leave -- until you finish what you set out to write!

Some craft books reviewed by Noor Qasim in the NYTimes Book Review "The Short List."

Here's something useful from the review aboutMatt Bell's book Refusing to be Done.

Qasim writes: "Bell structures the book around what he calls the novel's three provisional drafts: 'generative revision,' 'narrative revision' and 'polishing revision.' .... The abundant first chapter, outlining the basics of the "exploratory" initial draft, is carefully elucidated, if admittedly all about 'chaos.' In the second and third chapters, Bell attends to structure and style, guided by two principles. The first: 'One should 'rewrite instead of revise.' How to tell the difference? 'The presence of new typing … and the absence of merely copying and pasting.' Second: One must simply 'refuse to be done.' Where a less capable teacher might leave us wondering how, Bell holds us accountable with an exhaustive list of editing approaches, from pulling up widows to reading aloud to identifying 'weasel words.'"

Homework for This Week

Take a look at this scene from Elmore Leonard's crime novel Detroit:

Writing homework: Write a scene in which your main character is standing in a high place. Have the character observe, then focus on some particular element, then go into an interior memory, speculation, even flashback stimulated by what is seen.

Reading Homework: Read this material on Flashback and, if you haven't yet, this on internal monologue (character thoughts), and the materials on present tenses--it's pros and cons.

I. Business

Remember: No Class April 20-- everything gets moved one week forward (homework due by April 24, etc.)

Any questions at this point?

Next session: A mini-lecture on marketing. Presenters are Laurie-Maude Chenard; Jo Fekete; Linda Atlas

We'll continue with the NYU Zoom unless there's a problem

II. Mini Lessons

A little bit on tense and flashback.

"She sat sewing lace at the neckline of the gown she'd worn when she'd married my father." The second past perfect tense is not necessary: by convention, in novels, once we've established the "past of the past," we can proceed in normal past tense: "She saw sewing lace at the neckline of the gown she'd worn when she married my father."

Flashback

Tense Revision

III. Presenter One: Philip, Melissa, Alison

IV. WRITE

At a moment of action in your novel (perhaps the action you wrote last week) write an internal thinking passage for your main character. If you are writing in third person,it should probably be "free indirect discourse" or "free direct discourse"as we discussed a few weeks back.

The emphasis here is on keeping the thoughts flowing gracefully while action is underway: not as easy as it is in real life!

Free indirect discourse Character's expression and exact words without quotation marks. This is usually a mix of the character's words and the narrator's words: Oedipus was beginning to realize what he had done: It was murder! He had done the unthinkable and killed his own father.

Free direct discourse Character's own words at more length, presumably exactly what the character would say or think (but still without quotation marks): Oedipus paced back and forth as the realization hit him. I've murdered my own father! Could anything possibly be worse? But wait, what about the rest of the prophecy? What if.....? Gradually he realized that indeed something could be worse. (If this goes on long enough, it would be called internal monologue).

V. Presenter Two: Philip, Melissa, Alison

VI. BREAK

VII. Presenter Three: Philip, Melissa, Alison

VIII. Discussion on your relationship to revising. When do you do it?

IX. More Mini-Lesson: Some strategies and techniques for revision:

Tightening and Cutting! Never too much! At least in novels

Order of sentences

Consistency in a character's appearance AND behavior. What have I revealed?

Best technique: do a search for "Karen" and check all her details through the whole manuscript You can do this with action, too, or the appearances of certain places (do a add a new detail with each appearance).Take a look at the sample below from a novella of mine.

-- Tyler's New Clothes First version to second version: I just tightened. It's what I think of as soft,squishy sentences getting tougher and more wiry. . By the third, I was also making changes about what information is conveyed: information about the school, and the vice-principal. The original version has two women teachers talking naturalistically, but doesn't go very far with the story. I was still in my mind just listening to how they talked, to the relationship between the narrator and Fredda. It was about what can be observed on the surface. By the third version, I had what I wanted about the narrator and Fredda in other places. The final version, with the narrator and the vice-principal, is exploring a new character, the veep. It has more about the culture of the school.

I get tremendous pleasure in seeing the story come into view like this, like an old fashioned developer bath for photos. Another way I think of this is as sculpture: I get that elephant's general bulk hacked out, then the details that come into view.

Ideas on different drafts from the "In Brief" book review on Matt Bell's book: "Bell structures the book around what he calls the novel's three provisional drafts:

'generative revision' -- moving from drafting chaos to new ideas, rough order, new typing!d

'narrative revision' -- moving to structure--finding the story arc?

'polishing revision.' lots of editing and polishing approaches: reading backwards, reading aloud, etc. (More on this in the final session on special novel-revising issues and techniques.

X. Homework for TWO WEEKS from now-- due in my e-mail box on 4-27-22

Writing homework:

One-- e-mail me questions for the Marketing Discussion

Two: A revised passage--with my original notes.

Or--a revision-expansion of the internal thinking/internal monologue from today's class

Or-- anything you choose for response.

Reading Homework:

Read in more depth some of the links from today's class: Order of sentences ; Tyler's New Clothes ; Tightening and Cutting ; Tense Revision.

Here are a couple of interesting articles on revision: A close reading of a well-made first paragraph (Emily Temple on True Grit) and How some contemporary writers revise (from Lit Hub).

(Optional) Read Strategy 10 in Ten Strategies "Revise Your World."

Presentation Schedule

NO CLASS 4-20-22

Session 9.

4-27- 22

Marketing

Writing homework due:

One-- e-mail me questions for the Marketing Discussion

Two: A revised passage--with my original notes.

Or--a revision-expansion of the internal thinking/internal monologue from today's class

Or-- anything you choose for response.

Reading Homework due:

Read in more depth some of the links from today's class: Order of sentences ; Tyler's New Clothes ; Tightening and Cutting ; Tense Revision.

Here are a couple of interesting articles on revision: A close reading of a well-made first paragraph (Emily Temple on True Grit) and How some contemporary writers revise (from Lit Hub).

(Optional) Read Strategy 10 in Ten Strategies "Revise Your World."

I. Business

I want to draw attention to two articles:

-- How to put the latest technology in your novel

-- New at Practical Writing Journal: A story was submitted forty times over ten years, and finally published--the same day the acceptance arrived!

NYU Evaluation now ready to be filled out--closing tonight! See Course Evaluations here.

Final presentation pieces are due in my inbox by Sunday night. (Linda, Philip, and Melissa)

Homeworks turned in today will be returned 5-4-22

II. WRITE

Last "man" standing exercise: on the final page of your novel, who gets the last word? And what kind of word is it? (dialog? observation of the landscape? monologue? reflection on past events?) Where is your main character standing (literally) and what is she looking at, thinking about, doing? Is she alone, etc.? If it's a multi-point-of-view novel, who gets this final moment? Include what is seen, what is thought, whatever.

This kind of reflective moment is especially appropriate for novels--short stories, for example, don't usually have them.

III. Presenter One: Linda

IV. Presenter Two: Jo

V. Marketing and Publishing

1. Intro:

Today is a time of great flux--lines weakened between commercial publishing and so-called indie publishing (sometimes self-publishing, sometimes hybrid or subsidized or cooperative publishing). There are many models for publishing today, but making a living at it is less and less likely.

Returning to the Chaucer/Shakespeare/Jane Austen models?

There is a great deal of competition for the entertainment dollar!

The ideal, which I came in at the very end of, is that you get a literary agent who takes on book, sells to editor, who sells to her publisher, who edits, prints, sells, etc. You market your work to the agent (very genteely!), then the business is taken over by professionals. You were not really expected to "market" the finsihed product--maybe an all-expenses paid book tour.

This is still possible for a few, especially for nonfiction and for very commercial fiction.

Now, however, even with commercial publisher, authors are usually asked for a "platform" and sometimes to pay for their own copy editing and publicity.

"Independent" publishing has replaced "self" publishing, and it is not looked down upon nearly as much. It probably should not be your first choice though.

Note: even when I had a hotshot agent who placed my first novel with Scribner's, I placed my children's and literary short story book on my own. Agent just went over contracts and took her cut. Since my first three commercial novels, I've published with

another major New York publisher (children's novel)

several small presses that pay little or nothing

university presses that don't do advances, but do pay royalties

a cooperative press where writers share work and pay their own expenses

The world of e-book publishing without hard copies is a whole other kettle of fish: E-publishing is amazingly cheap, with often amazingly bad writing, and, especially with certain genres, has become a common outlet.

2. Give your first energy to getting your story andd the words it's written with in excellent condition.

3. Then, as you approach publishing, do some research.

Check out these Draft Notes on Getting Published

For an excellent outline on the basics of getting published, look at Jane Friedman's page. You may also subscribe to her blog.

Best general resources on places to submit, lists of writing programs and conferences and much, much more: NewPages.com.

Also excellent site for general information (literary agents, for example,)is Duotrope.com.

MSW's Resources for Writers has a lot of odds 'n ends.

Especially for literary writing, see Poets & Writers.

Notes on various types of publishing at Publishing Types and Print on Demand.

How long should a novel be? See notes on my Resources for Writers page.

A one-pager, somewhat out-of-date, of resources about getting published

See blog post by Veronica Sicoe on why she self-publishes and

A Wall Street Journal article about Marlen Bodden, a former student in one of my novel classes who first self-published-- and then had her book picked up by a commercial press. Note: self-publishing should never be you first choice, but it should be on your list of possibilities.

Another good resource: An online magazine called AuthorsPublish at https://authorspublish.com/ . Here's their free guide to traditional-style publishers who don't require agents.

4. Do these things as you feel ready to market your novel

First, get the manuscript in pristine condition--editors don't have patience for mess and mistakes. The competition's too great.

Experiment with submitting to online journals, magazines, & contests--short stories or novel-parts, or sections of your novel that can be edited to stand alone. This can be useful when you try to get an agent or editor, evidence that someone else appreciated your work. There are infinite possibilities on the Internet and also look at NewPages.com. Most online and other literary journals don't pay. They are, however, easy to submit, using something called "Submittable." Note also that many of them charge a reading fee of $3 and up.

On Facebook, search for "Calls for submissions (poetry, fiction, art.)" Sign up to get notices.

Peruse old standards like Writer's Market and The Writer and Writer's Digest and get on Jane Friedman's free newsletter list.

Read Jeff Herman's Guide to Agents.Lots of good stuff, oriented toward literary writing, at Poets & Writers.

Consider going to a writers' conference to make connections and learn more. Some people love these, but even if you don't, one conference should give you an overview and the vocabulary you need to proceed. And doing no writers' conferences is just fine too.

5. A Few Specific Marketing Questions: Some of these are answered in the links above.

Some general questions from past classes:

How do you copyright your novel to prevent someone from stealing the ideas and content?

Go online to http://www.copyright.gov for the latest information.

HOWEVER, from the moment you finish a piece of writing, the government recognizes that only you can decide how to use it. The law presently governing this is the copyright law of January 1, 1978. A piece of writing is copyrighted the moment you put it to paper. You may indicate your authorship with the word Copyright (or the c sign), the year, and your name, but this is not necessary. Protection lasts for your lifetime plus 50 years. If your work is anonymous or pseudonymous, protection lasts for 100 years after the work's creation or 75 years after its publication, whichever is shorter. None of this holds in the case of writing-for-hire. You do not have to register your work with the Copyright Office to receive protection. If you want to, however, you may request the proper forms from the Copyright Office, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20559.

What is the right number of agents to query at one time? They take so long, and not all of them even reply. Is there any reason not to send to a hundred in one gulp?

One agent said "Please, please don't sent stories about white dudes on quests." That covers a lot of ground. I am all for diversity but still hope to be published. Any advice on how to negotiate this variable?

Do aspiring writers have to be represented by a literary agent?

Some advise not to even mention past publications (in approaching agents) if they performed poorly in the marketplace. What do you think?

From Jo:

1. Are there terms we need to know when talking with publishers, or editors?

2. Are marketing kits helpful?

3. Do today's writers market their work at conventions?

4. Can you recommend a website that has helpful marketing materials and information?

5. How did you publish your first book, and those that followed?

6. Would Suzanne be willing to share her experience with marketing and publishing her work?

From Philip

Would it help to hire a top public relations firm to help promote the sale of

your novel effectively to the public?

From Jody

Do you mean marketing in the context of positioning your book so as to gain an agent and then a publishing deal?

When I hear the word marketing, it denotes to me that which happens upon distribution being secured, be it a film or a book. But it would seem you are referring to that which the unpublished novelist can do to help secure interest from industry?

The same happens with indie film, in a way, but that normally involves a festival premiere and related positive publicity generated, as well as some social media presence. Is the book world the same? Are there noteworthy festivals or forums for unpublished writers and work that help garner attention to then hopefully attract lit agents et al.?

From Alison:

I'm craving information about where I can go for help with my query.

VI. BREAK

VII. Presenter Three:Laurie-Maude

VIII. Writing homework:

Final presentation pieces are due in my inbox by Sunday night. (Linda, Philip, and Melissa)

Reading Homework:

-- MSW's article "Seven Layers to Revise a Novel"

-- (Optional) If you didn't read it yet, in Ten Strategies go over "Strategy 6: Structuring Your Novel."

-- Also, if you didn't yet, look over the following short pieces in preparation for the second revision session. Order of sentences ; Tyler's New Clothes ; Tightening and Cutting ; Tense Revision.

Presentation Schedule

Session 10.

5-4-22Revision Two: Revising Novels

NOTES FROM LAST WEEK:

One Story classes

Anthony Doerr novel Cloud Cuckoo Land.

Homework due:

-- MSW's article "Seven Layers to Revise a Novel"

-- Also, if you didn't yet, look over the following short pieces in preparation for the second revision session. Order of sentences ; Tyler's New Clothes ; Tightening and Cutting ; Tense Revision.

-- (Optional) If you didn't read it yet, in Ten Strategies go over "Strategy 6: Structuring Your Novel."

I. Business:

-- Last call if you don't want a grade!

-- This web page willl be up for at least a month so you can get to the materials to save or copy. I'll take it down, though, by early June.

II. Follow up to last week's Marketing discussion

Laurie-Maude Chenard on agents

Suzanne Martinez on places to submit short fiction

III. Presenter I:

Philip Ai

IV. Presenter II:

Melissa Franke

V. Write

Put a storage container in your novel.

This could be a sock drawer, a backpack or fanny pack, a warehouse, a refrigerator-- whatever. It may have something to do with the plot. See where it leads you.

VI. Break

VII. Mini-Lecture: Revising Novels

A. Overview:

This is going to be another mini-lecture that will be mostly me directing you to materials.

My general remarks are mostly about my own process.

Thus, before you do anything else, get a lot written. That is, if you need to revise as you go, do it, but do less than you may want to. Going over what is written is reassuring. We know how to make it better. Voyaging out with new material if scary, but you need a lot of material for a novel. Get something roughly novel-sized written before you make final decisions.

Here is a gross over-simplification of my process:

-- Draft the whole thing if possible

-- Go through again, primarily adding and enriching.

-- Go through again moving things around to find the best order to tell your story--consider conflict, crises, story arc, climax (es) etc..

-- Go through again cutting and tightening. Respect your audience's time!

-- Go through for housekeeping. Clean up grammar, continuity, etc.

-- Let it sit, maybe a long time.

-- Go over it again.

B. Seven Layers

I hope you'll read and/or print out my "Seven Layers to Revise a Novel."

I want to point out a couple of crucial "layers:"

1. Do a revision from the middle or three-quarter point. This will focus you on the final sections which often don't get the close attention the beginning does.

2.The character/place/other proper name check: Do a search for every appearance of an individual character or room or city etc. Read just those parts to see what is missing, if you have been too repetitive, if you can spread out some of the descriptive details.

3. "Continuity" can flow from #2. Check for the hero's eye color. Does it stay chocolate brown and turn steeling gray fifty pages in? This is part of housekeeping, and since you are the whole crew for your novel, you're responsible.

C. Another approach

Something I just found in the new issue of Poets & Writers (May June 2022). I recommend this publication anyhow, at least to look at occasionally: craft articles, classifieds, contests, conferences, etc. Eight Final Revisions to Try Before You Submit by Matt Bell.

A lot of his is probably more appropriate for short stories, but I especially like these two ideas: 1) Go through only the dialogues--all of them, 2) and cut the weakest sentence from every paragraph (I'd suggest picking one chapter or section to try this on).

D. A One Page List of Novel Revision ideas

VIII. Presenter III:

Linda Atlas

IX. Discussion

What are your immediate plans for continuing, finishing your novel? Conferences, classes? A month in a cabin? Classes?

X. "Homework"

Here are some starters and restarters to try if you are away from your novel for a while or get stuck. Most of them are common objects or situations to put in your novel and see where they take you. Print out or download the .pdf and keep it handy.

Make up your own!

XI. Farewells!

Carolina DeRobertis, Margaret Atwood (her stamp!); Edwidge Danticat Second row: Octavia Butler, Franz Kafka, Charles Dickens, Toni Morrison.

All assignments should be PART OF YOUR NOVEL. You may substitute any short section for the assignments, keeping in mind that the total submitted to MSW may not be more than 50 pages..

Iimages are stock photos or borrowed.

If you are presenting, please get the piece to the class by midnight on the Sunday before your presentation.

Session 2. 3-2-22

Jody Girgente

Alison Hubbard

Suzanne Martinez

Session 3. 3-9-221

Jo Fekete

Session 4. 3-16-22

Laurie-Maude Chenard

Alison Hubbard

Isabella Barrengos

Session 5. 3-23-22

Suzanne Martinez

Jody Girgenti

Session 6. 3-30-22

Jo Fekete

Isabella Barrengos

Melissa Franke

Session 7. 4-6-22

Laurie-Maude Chenard

Suzanne Martinez

Jody Girgenti

Session 8. 4-13-22

Alison Hubbard

Philip Ai

Melissa FrankeNO CLASS 4-20-22

Session 9. 4- 27-22

Laurie-Maude Chenard

Jo Fekete

Linda Atlas

Session 10 5-4-22

Linda Atlas

Philip Ai

Melissa Franke

Various NYU Policies

Course Description: Beginning with a discussion of the basic elements and structure of novels, the class will include instruction and exercises for those just getting started, as well as a serious exploration of how to organize novels and other long prose narratives for those writers with projects already underway. Writing exercises will cover shaping, establishing tone, exploring character, tightening and enriching dialogue, and working with interior monologue. Topics for discussion will include sustaining interest for the writer as well as the reader, making a place in your life for your novel, and highlighting what novels do that film can't. We will look closely at up to 50 pages of manuscript from each participant. This syllabus will be updated regularly online, so please check this website at least once a week at http://meredithsuewillis.com/nyunovelwriting%20spring%202018.html

Course Prerequisites: Interest in novel writing.

Course Structure/Method: This in-person class uses short homework assignments, in-class writings, class discussion and regular critique. Please check the class website (http://meredithsuewillis.com/nyunovelwriting%20spring%202018.html ) at least weekly for changes.

Course Learning Outcomes: By the end of this course, students will have lengthened their novels and gained insight into how to continue and deepen their fiction.

Communication Policy: Communicate with the teacher via her e-mail: meredithsuewillis@gmail.com. She tries to get back promptly, but is a working writer with family and civic responsibilities.

Course Expectations: Homeworks are due as described on syllabus, but subject to change and substitutions are allowed. See website for updates. Attendance and class participation are expected.

Required and Recommended Material: There are three kinds of required readings: passages from the text Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel as detailed on the syllabus; any student samples for critique that are distributed; certain short readings online.

NYU Policies: NYUSPS Policies regarding the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), Academic Integrity and Plagiarism, Students with Disabilities Statement, and Standards of Classroom Behavior among others can be found on the NYU Classes Academic Policies tab for all course sites as well as on the University and NYUSPS websites. Every student is responsible for reading, understanding, and complying with all of these policies. The full list of policies can be found at the web links below:

• University: http://www.nyu.edu/about/policies-guidelinescompliance.html

• NYUSPS: http://www.nyu.edu/about/policies-guidelinescompliance.html

School Grading Policies: Graduate, Undergraduate and Non-Degree grading scales are very different. Please provide the link to the grading policy appropriate for your course. The links are listed here.

NYUSPS Graduate http://sps.nyu.edu/academics/academic-policies-and-procedures/graduate-academicpolicies-and-procedures.html#Grades

NYUSPS Undergraduate http://sps.nyu.edu/academics/academic-policies-and-procedures/undergraduateacademic-policies-and-procedures.html#Grades_and_Grade_Point_Averages

NYUSPS Career Advancement (non-degree)http://sps.nyu.edu/content/scps/academics/noncredit-offerings/academic-noncreditpolicies-and-procedures.html NYUSPS Diploma (non-degree) http://sps.nyu.edu/academics/academic-policies-and-procedures/diploma-academicpolicies-and-procedures.html#Good_Academic_Standing